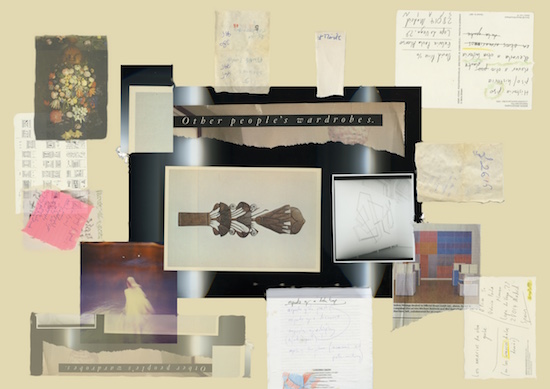

Floor Story (other people’s wardrobes) (Madrid) by David Price

Imagine a hypothetical artist has taken up a teaching post at a venerable American art school. An older man, whose work used to be very prominent sometime in the early 1970s, he remains well respected, still bought and discussed, but certainly no longer ‘current’. He has, perhaps to his credit, gone on saying the same thing for years.

There is something that vaguely annoys him about what is sometimes called ‘the rise of the curator’, and the thought that however much a curator might respect, treasure, think about or even love works of art, they will always have a thesis whilst assembling an exhibition, and that the artworks used within the exhibition will illustrate this thesis in some way.

He has been asked to curate an exhibition at the university, and he keeps thinking about how bizarre it is that American art schools often refer to their postgraduate ‘degree shows’ as ‘thesis exhibitions’. This is grossly distasteful to him. Art should BE discourse, it shouldn’t be a discipline where people are taught to make works that sum up discourse! He decides to confuse and annoy everyone, especially the Dean of the University, by also calling the show he will curate, ‘Thesis Exhibition’.

The exhibition will be made up of text works, especially works that only make use of one or two words. He will NOT allow these words to form a sentence. That would be too easy.

He calls some friends at a few museums, and some collectors and artists he knows, and sets about borrowing a Joseph Kosuth (not the ‘Chairs’ though, maybe ‘Clocks(One and Five)’), an Ed Ruscha (not one of the proper paintings, but one of the lighter ones. The one made with carrot juice, ‘The World’). He will also put in an old work of his called ‘Of Breasts’; a piece of writing in pencil on paper spelling out the words ‘…des seins’. A lot of his work is basically lascivious, but pretends not to be by being rather formal in appearance, and by containing word games, other languages, and respectable intellectual puzzles.

The university also has a collection of Walker Evans photographs, so maybe the one called ‘Truck and Sign’ that just has the word ‘damaged’ partly obscured by a truck.

How about a neon? Everyone makes neons…

Pádraig Timoney, Fontwell Helix Feely, Raven Row, 2013. Photo by Marcus J. Leith

For artists who arrange exhibitions, the process often takes the form of a serious digression, a temporary route out of their singular practice and into another’s. It is a way of making their practice plural, collaborative, and also self-reflexive. Arranging an exhibition necessitates seeing and thinking about each work individually, as a unit, but also achieving a perspective through which several such units are placed in harmony (or, sometimes, in discord). This perspective, once achieved, is something like an extruded diagram that shows individual units as the related components in a system.

In the process of arranging an exhibition, an artist’s subjectivity digresses to include: the work of others, a space, an institutional context, practical arrangements, &c. These considerations are all prismatic in regards to the artist’s subjectivity as an artist. Like someone who takes on a new form of exercise that they’re not used to, they develop aches in ‘muscles they never knew they had’. But far from being annoying, this is fundamentally invigorating.

The artist can also be quite carefree with the artworks involved, in some ways. The artworks can, and should, be allowed to speak, but not to follow a script of any kind. They can be allowed to babble away, and the exhibition will be the result of this babble. This is fine. Maybe some new meanings will be created, after all. A productive synthesis of a thesis and an antithesis that were never really in opposition.

All of this takes place in a certain part of the artist’s mind, a different wing of the building to the studio, or to exhibition spaces curated by curators. It is, at least potentially, a form of ‘internal collaboration’. It means being able to practice a kind of stylelessness, or being able to flatten out a multiplicity of styles at once (including that of the artist themselves): ‘making something’ of a diversity of works and a diversity of authorial voices.

An artist who manifests quite clearly the sensibility of stylelessness that I’d like to claim as digressionary is Pádraig Timoney. His exhibitions are said to resemble group shows. In a short essay by Alessandro Rabottini written to accompany the exhibition ‘Fontwell Helix Feely’ (at London’s Raven Row gallery in 2013), this avoidance of recognisable style is described as something the artist practices with “extreme and paradoxical coherence”, achieving a “radical eclecticism”.

In presenting works that do not resemble one another, Timoney not only fragments the subjective authority we might expect to find when many of an artist’s works are gathered together, but disables the viewer’s ability to discern a subjective thesis in the totality of the works. The exhibition, in fact, becomes an assembly where, according to Rabottini, “each work as a distinct unit (become) coordinates”. This is, perhaps, a way of fragmenting the singular authorship of an ‘artistic practice’ until it can form a ‘curatorial practice’. I see this as a highly productive state of permanent or ongoing digression.

I started writing this in response to a text of Joseph Kosuth’s called Writing, Curating and the Play of Art. Kosuth asks why it is so shocking when “artists talk back”. After a discussion of his own curation (or ‘organisation’, as he puts it), Kosuth starts to think about what happens differently when “an exhibition is a work of art itself”, when “the artist takes subjective responsibility for the ‘surplus’ meaning that the show itself adds to the work presented in it”.

This notion of a ‘surplus meaning’ that, according to Kosuth, is the synthetic product of an exhibition curated by an artist, is a way in which digressionary meaning is allowed to germinate without being strategically ‘meant’ as such, in order to illustrate a thesis. Units of meaning that are firstly recognised as such, and then put into play, form the discourse of the digressionary subject.

This seems close to the model observed by Rabottini in the work of Timoney: distinct units that become coordinates. Or, as Kosuth goes on to say, his curation “is not unlike a writer’s claim of authorship over a paragraph, comprised as it always is of words invented by others”. Kosuth has some specific axes to grind in this essay (the mistreatment of thinking artists by critics at the end-point of modernism, in particular), but the generosity of the offer he makes to the viewer, in showing – but not ‘meaning’ – meaning, is the pertinent, productive ambiguity I wish to highlight.

Pádraig Timoney, Fontwell Helix Feely, Raven Row, 2013. Photo by Marcus J. Leith

Imagine that a young artist finds themself at a university, enrolled on a postgraduate Fine Art course that feels, to all intents and purposes, like a philosophy course. Everything that is discussed has the atmosphere of being hypothetical. It is not that she and her classmates don’t make anything, or don’t occupy studios that contain tables, wood, metal, paper, tools, objects, etc. But it is as if everyone pretends that these objects are physically inert. At best, the materials used by the young artist and her classmates are combined into ‘works’, but these works are discussed strictly in terms of the proposals that they might form as regards the possibility of constructing meaning as an artist.

She is aware, in a more or less tangible and somewhat exciting way, that this feels like an intellectual way of making art but there is something missing from the process. The extreme priority given to the making process as a means of testing hypotheses feels as if it’s a way of making sure hypotheses are never tested, of maintaining all objects and thoughts strictly as units of potential meaning. A lot is thought, but very little is thought through.

She contemplates organising an exhibition that would arrive in the school as a polite alien for whom the practical nature of meaning is a problem to be solved. The exhibition will be called ‘IRL’, after the internet acronym for ‘in real life’. The first criterion for this exhibition is that objects might be shown AS themselves, not ‘as themselves’.

The university’s museum has a small ethnographic collection of objects, which are almost never displayed. She selects from this collection a flint axehead. This is, of course, not just an object – someone sharpened it at one point. It has been ‘made’ to some extent. But the making undertaken – the act of sharpening – was more or less harmonic with the nature of the piece of flint in the first place. It was already sharp, and suggestive of a blade, and its prehistoric maker just added to the flint’s sharpness.

Perhaps a piece of modernist painting would go nicely next to this: something that had little to do with anything except paint. Ideally, a Frank Stella would go well here, or even better a Malevich square. But not a Malevich that looks like the ones one sees in museums now, slightly ragged and not in the least bit superficial in character. Perhaps, she thinks, an ideal form of Modernist work could be fabricated instead.

She paints her own, brand new, black square, but it doesn’t quite feel right. The paint feels like a distraction from what the work really is, what it’s trying to be. Maybe it wasn’t about paint, or flatness, in the first place. She creates a black square using Photoshop, and prints it out. It looks good. Pretty black. But it’s still undermined somewhat by the nature of the ink, the nature of the paper…

Instead she decides to just present the idea of the black square in the simplest way possible: the digital RGB values of the colour ‘black’ are ‘0 0 0’. No colour. A lack of tonal dimensions. So, instead of a piece of modernist painting in the exhibition, there will be a text saying: “A digital image of a black square measuring 0 cm x 0 cm x 0 cm”. She is fully aware that these dimensions make it a (hypothetical) cube rather than a square, and one that occupies no space whatsoever, but this seems both funny and productive: the hypothetical work is therefore a sculpture as well as being a painting, whilst being neither.

Three dimensions… maybe the exhibition should just have three works in it. A tool, the idea of a cube, and what else? It would be nice to have a person, a performer… probably not possible to get Marina Abramovich. Anyway, a real performance artist like that would bring a past with them, a critical past, a celebrity past, a personal past. It would be better if the performer were just a person, who was only activated as a ‘performer’ momentarily. So she decides to simply mark an ‘X’ on the floor of the exhibition space.

This ‘X’ designates the site of the performance. Occasionally, whenever someone happens to stand on the ‘X’, the performance would be taking place. This might happen often at the opening of the exhibition, and less often after that. She tests this, and stands on the ‘X’ for a moment. Nothing happens…

Art & Language, Speaking of ‘Nobody Spoke’, Theory Installation by The Jackson Pollock Bar, 2014, © Art & Language; courtesy Lisson Gallery, Photo: Ken Adlard

Somewhere within a recorded conversation with Art & Language from 1973, the members of the conceptual art group discuss the possibility of introducing forms of “interpretation” and reflexive thought into artistic practice. They speak of a practice that “takes into account … the idea of one’s study being intensive as distinct from extensive”. This suggests, at least, something beyond being reflective and seems to propose a practice that works back into itself.

The digressionary subject, the artist-thinker, the artist-arranger, is made manifest in the work of Art & Language in quite a clear way. Thinking about art can be part of making art as well as being a part of discussing it. In modernism, something like this happened to the material form of art. But at the end of modernism this pursuit of critique became about the very ontological viability of art. It proposed that the making of art was a curation/arrangement/consideration of possible concepts, implications, resonances, histories, notions of the future and present of the form, of names for making, names for thinking, reasons for making, reasons for names, and so on. And, if nothing else, it did so by testing its own hypotheses.

A work need not be ‘a’ work, need not be fixed, need not be singular. It might instead be a co-ordinate aligned against others, it might be one of many meaning-units, it might invite collaboration (either an internal collaboration with one’s own previous or current work, or with the work of others, or with the ghosts of others, or with the metaphors these ghosts suggest), it might be a part of the machine that produces Kosuth’s ‘surplus meanings’. Not only artists arranging things for themselves, but artists producing via arrangement, and arranging via production.

This is an argument for things to take digressionary forms, to branch out, to avoid being singular. To avoid ‘style’ if at all possible. In this respect, and in this respect alone, this essay is an (admittedly) meandering and digressive manifesto. Not so much a call-to-arms as a call-to-branches. But a call nonetheless.

David Price is an artist and lecturer at the CASS, London. For a more extensive – and even more digressive – investigation of digressionary subjectivity, please check out his website