The delicious-sounding location of Onkalo, Finland is home to the world’s first deep geological repository for spent nuclear fuel. Still under construction, but designed to be operational for at least one hundred years once it is complete, this facility aims to tackle the problem of nuclear waste on a geological timescale. The half-life, or the rate of decay, of many nuclear isotopes can stretch into thousands of years, which means that nuclear waste will remain dangerous long after you and I have kicked the bucket. According to Michael Madsen’s 2010 documentary on the subject, Into Eternity: A Film For The Future, the nuclear waste stored at Onkalo will not be safe for another 100,000 years. This begs the question: As the cultural tide shifts back into acceptance of nuclear power as a ‘sustainable’ resource, how do you ensure that future generations become aware of the fact that this location is extremely dangerous?

Thank You For Your Patience, which premiered at the Hackney Showroom in July, is a play that attempts to answer this question by exploring the idea of intergenerational equity in relation to nuclear culture. Written and performed by Hector Dyer, with an accompanying soundtrack by Rob Morton, the work takes the Onkalo spent nuclear fuel repository as its principal starting point, before deviating into alternative narratives, one of which is set in an unnamed British village, and the other, in a harsh, but distant future.

The latter narrative tells the story of people who stumble across a contaminated geological repository. How do they interpret what they find? Building on Madsen’s film, Dyer’s monologues introduce the problem of semantics with respect to long-term nuclear storage solutions. Languages are constantly evolving and our understanding of semiotics can change significantly as generations succeed one another. The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) and the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) recognised this problem and, in 2007, published a new symbol to represent the danger of ionising radiation, with the aim of replacing the old trefoil image with something more intuitive.

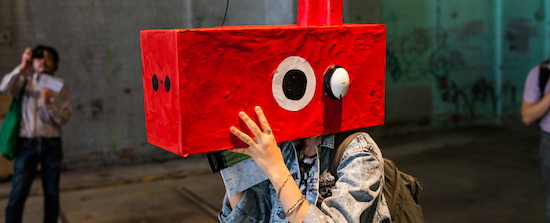

Rob Morton & Hector Dyer – Thank You For Your Patience, 2017, Photograph by George Galkin

Catching up with Morton and Dyer after their performance, I couldn’t help but ask them why it was that they found this subject intriguing enough to write a play about it. Crouching on a slither of artificial grass outside of the Hackney Showroom, Morton paused for a moment before answering: “The idea that you could leave a warning to people – they might even speak the same language, but [the message] just has no cultural meaning – gave us lots to work with”. Dyer continued his colleague’s train of thought: “We also felt that the concept of it being set 100,000 years [into the future] goes beyond our perception of time, and that allows you to write fiction that goes beyond our perception of what human beings will be”.

Whilst Dyer’s monologues deliver a wealth of dark and complex ideas, Morton’s soundtrack drives the play by providing a contextual backdrop and much needed colour. Rather than being a supporting agent, however, Morton’s music comes to the foreground by melding together dubstep, jungle, vapourwave and field recordings. In the process, Morton’s electronic atmospherics recall sounds from a “deconstructed club scene, people like Total Freedom or Bala Club. It’s very noisy, aggressive stuff that’s meant to be played at nightclubs, but just isn’t danceable at all”.

Don’t Follow The Wind – A Walk In Fukushima, 2016-, 20th Sydney Biennale, Photograph by Leila Joy

A little research into the concept of nuclear culture reveals that Dyer and Morton are far from the only artists interested in exploiting the atom. The Nuclear Culture Sourcebook, edited by Ele Carpenter and published last year by Black Dog Publishing, is an excellent resource on the intersection of art and what Carpenter calls “the nuclear imaginary”. Concerning itself primarily with the visual arts, the book’s most chilling example of how far artists will go to highlight the dangers of nuclear power is film documentation from the Don’t Follow The Wind exhibition.

This collaborative show was initiated by the Japanese neo-Dada collective Chim-Pom. The collective assembled works by various artists, which related to nuclear culture, and exhibited them at various locations in the Fukushima Exclusion Zone. Due to the extreme contamination levels of the site it is impossible to tell when the exhibition will be open to the public. Its duration, therefore, is indefinite. However, the collective’s hand-made virtual reality headsets (above), most recently available to view at the Art Catalyst show Real Lives Half Lives: Fukushima, earlier this summer, are able to place the spectator right at the heart of the devastation, which followed the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster of 2011.

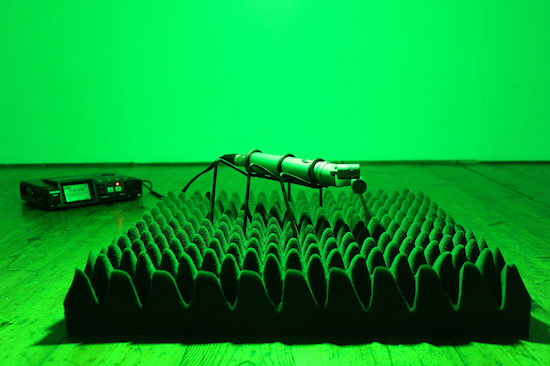

Peter Cusack – Chernobyl Frogs, 2012, Field Recording

Working a little closer to home, the experimental musician, Peter Cusack, made field recordings of various nuclear sites, most notably inside the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone. Divorced from context, field recordings can often be a difficult sell, but Cusack provides a short blurb for each piece of audio. Compiled in the 2012 book, Sounds From Dangerous Places, these recordings offer a glimpse into a largely abandoned, eerie environment where nature has usurped mankind’s dominance, yet the invisible dangers of radiation linger in the background.

The theme of invisibility is also pervasive in the work of Mark Peter Wright, a sound artist whose main focus has been the exploration of the Anthropocene, a familiar theme to some readers of tQ. Whilst this new geological time period does not immediately suggest notions of the nuclear, Wright traces its proposed beginnings back to 1964, “which saw a peak in radioactive carbon following two decades of nuclear weapons testing”. Wright’s sound works rarely involve sound at all, but rather focus on its absence. His mutating microphone sculptures (Humanimentical Prototype) and wandering deadcat Sasquatch (I, The Thing In The Margins) suggest that, like Dyer, Wright is also interested in fictions that go beyond our perception.

Mark Peter Wright – Humanimentical Prototype, 2015, Image courtesy of the artist

The Japanese cultural critic and art anthropologist Noi Sawaragi, who contributed an essay to The Nuclear Culture Sourcebook, summarised the close relationship of art to nuclear culture: “When people think of ‘art’ they imagine the visual arts, but like radioactivity, art too is invisible. When we encounter art, what we tend to see is merely the artwork-as-substance. And while the artwork-as-material is visible, we still might fail to appreciate the experience or meaning of the material that makes it art. We expect to experience an abstract power of art, something emanating, invisibly, one might say, almost like radiation”.

Although the nuclear industry takes strict precautions and reactor designs have improved over the years, Chernobyl and Fukushima prove that major accidents do happen. So do smaller, clearly avoidable ones. Furthermore, the gung-ho approach of the Trump administration to North Korea’s fits of attention seeking, coupled with the reactionary stance from the Labour party to Jeremy Corbyn’s attempts to scrap Trident, only go to show that we are still living in the Atomic Age. As our bold new century moves forward, I expect that issues relating to the "the nuclear imaginary" will increasingly become one of the primary concerns for socially conscious artists operating in sound, performance, and multimedia.

The Nuclear Culture Sourcebook is available now, published by Black Dog Publishing