“May I blow my own trumpet – immodest tho’ it may seem – to tell you that I am particularly interested in illustrated books and I should welcome the opportunity that never seems to come of illustrating a contemporary author. My own efforts in book work have so far been deplorable, but I unhesitatingly put the blame on the publisher in each case, because – as you know – publishers are always quite unmanageable. However I say no more …”

Thus wrote the twenty-seven-year-old Edward Bawden to Mr Parsons of Chatto & Windus in a typically self-mocking letter dated 17 February 1931. This despite the fact that he already had a respectable body of dust-jackets and other illustrations – particularly Robert Paltock’s The Life and Adventures of Peter Wilkins – to his credit. A few years later, as we shall see, when confronted by a particularly critical contemporary writer, he wrote in frustration to Jock Murray: “When will writers cease to be consulted by publishers on the question of the wrapper design! Shall I see that happy day!”

Edward Bawden, CBE, RA, draughtsman, water- colourist, poster designer, illustrator and muralist, was 20th-century Britain’s most diverse, inventive and prolific designer of book jackets. Born in Braintree, Essex, on 10 March 1903, he made his mark early at the Friends’ School in Saffron Walden by drawing unkind caricatures of his teachers, with the result that the head recommended he spend one day a week at the Cambridge and County School of Art. When he left the Friends’ School in 1919, his parents agreed to him attending the art school full-time provided he lodged with a “good chapel-going family”. While he was there his first illustrations were published, several of them being reproduced in The Drawing Pin, a student magazine.

Being ambitious to earn a scholarship to the Royal College of Art in South Kensington, but not confident of getting one in the set disciplines of painting, sculpture and drawing, he opted for ‘industrial design’ – which basically meant calligraphy – claiming later that although he had no particular interest in the subject, he was always happy to tackle something new. It was a fortunate choice as not only did it gain him his scholarship, but also was to stand him in good stead throughout his life, especially in terms of his designs for book jackets, advertisements and posters. He enrolled at the Royal College of Art at the beginning of the autumn term 1922, on the same day as Eric Ravilious, and they were both admitted into the Design School under the direct charge of the professor, the great Arts and Crafts polymath Robert Anning Bell. Edward Johnston also taught in the Design School, though Bawden claimed to have attended only one of his lectures. Another student who enrolled at the RCA at the same time was Douglas Percy Bliss, an English Literature graduate from the University of Edinburgh. Bliss was three years their senior and was in the Painting rather than the Design School, but an immediate affinity developed between the three of them.

The premises of the Royal College of Art in the 1920s were, as an adjunct of the Victoria and Albert Museum, still very much an integral part of ‘Albertopolis’ – the realisation of the Prince Consort’s vision for the creation of a cultural centre on the site of the Great Exhibition. A door from the Design School gave students direct access into the museum, and Bawden spent many hours familiarising himself with other cultures, as well as studying the watercolours of John Sell Cotman, Francis Towne and Samuel Palmer. These academic studies were further augmented by a travelling scholarship to Italy in 1925, so that by the time he left the RCA he had not only mastered the crafts of line engraving and linocut printing but also developed his own inimitable style of drawing and calligraphy. His earliest commissions for the London Underground were already under his belt, as well as the dust-jacket for Lance Sieveking’s The Ultimate Island and the Poole Pottery booklet.

The craft-skills he had acquired, coupled with his almost uncanny ability to draw repeat pattern freehand – backwards, forwards, sideways or upside down if so required – made him the ideal artist for the Curwen Press, drawing swelled rules, decorative borders, etc. He exploited this skill in his Baroque border design for Chatto & Windus’s Centaur Library edition of Richard Hughes’s A High Wind in Jamaica, the section-title drawings for the 1939 Week-End Book and the title pages to Ambrose Heath’s series of Good Food cookery books. Eric Ravilious’s future wife, Tirzah Garwood, who met Bawden about this time, later recalled that he drew with great precision and accuracy, and was quick at assimilating new ideas: “His early pen drawings were remarkably mature and it was in this medium that he first impressed those people who saw his work. He was meticulous and painstaking, wiping the ink off his nib before every dip in the ink pot to avoid any clogging lumps on his pen. With a perfectly steady hand, he could place a ruler on a still wet drawing and rule confidently on it with ink.” However, for the jackets of the Ambrose Heath books – Good Food, More Good Food, Good Drinks, etc. – he resorted to beguilingly simple linocuts rather than line- drawings, revelling in the different textural effects that could be achieved through inking, ranging from the colour-starved jellies on the cover of Good Sweets to the sumptuously erotic asparagus adorning Vegetable Dishes & Salads.

Bawden’s pre-war designs, which really culminate with the last of the Ambrose Heaths, have an innocence and naivety that he never revisited post-war: both he and the world had changed. As an Official War Artist, he was first in Normandy. Then later, when stationed in Cairo, he travelled extensively all over Egypt, Ethiopia, Sudan and Iraq. He was aboard the Laconia when it was torpedoed, and subsequently spent five days in an open boat before being rescued by the Vichy French and interned in Morocco. In the light of these experiences, it is not surprising that his post-war work was tougher, the humour darker and less spontaneous. One of his first post-war commissions was for the jacket of Albert Camus’s The Outsider (1946), for which his recent North African experiences and his acute observation of the Arabs provided ready material. And they did again the following year when he collaborated with Robert Serjeant, the Scottish scholar and traveller, on The Arabs, a Puffin Picture Book, printed lithographically at the Curwen Press and published by Penguin.

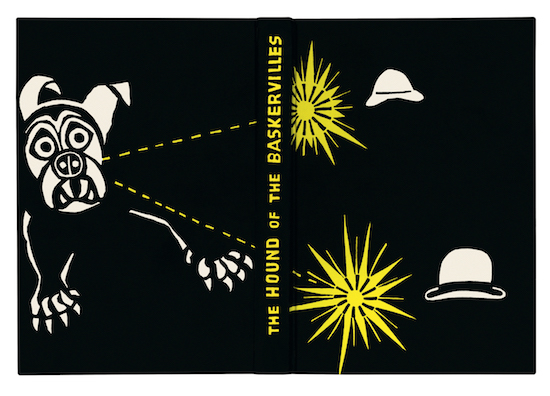

During the last decades of his life, the Folio Society fulfilled for Bawden the role that Faber had in the 1930s, commissioning the main body of his illustrative work; for their last two joint projects, Sir Thomas Malory’s Chronicles of King Arthur and The Hound of the Baskervilles, he reverted to his favourite medium of linocut. For a man approaching his eightieth birthday, illustrating the three volumes of Morte d’Arthur was a daunting task, but he enjoyed the challenge, revelling, as he said, in depicting all the “bloody bits” that Burne-Jones had left out. Bawden’s love of mediaeval church brasses, which had manifested itself in one of his earliest surviving teenage watercolours, The Schoolroom at Saffron Walden (now in the Fry Art Gallery), and informed dust-jackets of the 1960s, such as those for Alfred Duggan’s The Cunning of the Dove and Count Bohemond, achieved its apotheosis in these seventy-one black and white Arthurian cuts. Only a master artist, humorist and pattern-maker, using this restricted medium, could create such exuberant vignettes of battle, death and destruction.

Are You Sitting Comfortably: The Book Jackets of Edward Bawden is published by the Mainstone Press. Edward Bawden at Dulwich Picture Gallery opens on 23 May