Sir Antony Gormley has never played Minecraft. “But somebody showed it to me for the first time,” he says excitedly when I bring it up. “It’s absolutely extraordinary!” There is something about his blockish human forms, what Time Out’s Howard Halle called his “digital cubism”, concrete and metal men made of ill-matched cuboids in suggestive alignment, that recalls the exaggeratedly pixely sprites of Markus Persson’s award-winning world-building game. “There is a bit of that in there, isn’t there?” Gormley ruminates.

But he balks when I suggest that the figures in his show might be considered as avatars in some sense. He hums a bright “mmm” with a gently rising inflection that I take to imply a kind of affirmation without commitment, a lack of resistance to the word per se but an unwillingness to be bound by its associations.

Gormley’s new exhibition, Fit, subdivides the South Gallery of the White Cube’s Bermondsey space into fifteen different chambers containing, between them, twenty-four mostly new works comprising close to 550 sculptures. They range from the oblique cast iron climbing frame, Run, to more evidently referential effigies like Pose and Big Shy. But all of them are based, one way or another, on abstractions from the dimensions of Gormley’s own body.

“The show is really about what it means to inhabit a body,” he says at the press conference in the White Cube’s little auditorium, “but also what it means for a body to inhabit a space.” He sits on the stage with his legs stretched out before him, one ankle over the other, arms folded, lips pursed. Pondering the questions posed by the gallery’s director Andrea Schlieker, Gormley will look up and to the right from behind his spectacles. And, when answering, will allow his hands occasionally to escape the knot at his chest to execute slow, flat-palmed karate chops to emphasise a point.

The show’s title, he says, could as well be “fit question mark … the word is an invitation, but also an interrogation, asking who are we now? Now that we have external brains, and that we are dependent on everything that the urban brings us…”

Antony Gormley, Sleeping Field, 2016 © the artist Photograph © Stephen White, London

We have all had encounters with Gormley’s work in one way or another. From the now-iconic Angel of the North and the increasingly barnacled iron figures on the shore of Crosby Beach to Event Horizon, the extensive series of full-body casts that watch over London like Wenders’ angels over Berlin, they have become increasingly ubiquitous in our public space, coming to define, in some sense, the very meaning and purpose of public art in the late twentieth and early twenty-first century. “Sculpture is of its nature a collective good,” he answers to a question from the floor. “It doesn’t need the wonderful conditions of a gallery.”

I recall standing outside Chalk Farm’s Roundhouse a year or so ago, enjoying a mid-gig cig and idly surveying my surroundings, when I spotted a human figure on the building’s roof. I soon recognised it as one of Gormley’s cast-iron doppelgängers. But what stayed with me was the sense of paradoxical fragility presented by this hard metal image of manhood. He looked dangerously exposed up there, as if he were inclined to jump.

Does it ever feel strange, I ask, to encounter yourself, perhaps around London – these models of yourself?

“But they’re not me, are they?” he insists. “They look strangely like statues, but actually they’re not, because they’re not because they’re not representations. They are just examples of a human form in space that is of a particular person but it could be anyone. I don’t recognise them as me. I think that’s not the point.”

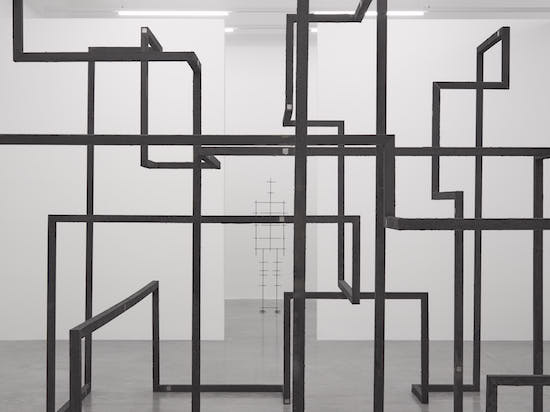

Antony Gormley, RUN, 2016, Cast iron, 109 1/4 x 125 7/16 x 166 1/16 in. (277.5 x 318.6 x 421.8 cm) © Antony Gormley. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

Sitting side-by-side with him in straight-backed chairs, I can’t help but adopt the attitude of the eager, young student at the feet of a distinguished professor. At a certain point I notice that we are both sitting with our legs crossed at the knee, left over right. Had I, deferentially, echoed his posture or was he ingratiatingly mirroring mine? Gormley wears all black with just the collar of a crisp white shirt poking out of a woollen v-neck jumper. Only once so sat did I notice that his socks, too, stuck out in an olive green. His sole diversion from an otherwise binary-coloured uniform.

“The question I’m asking,” he tells me, “is, if we are the only biological animal that chooses to make a context, a habitat for itself that is the most abstract you can imagine, these planes of pure horizontal and vertical walls and floors – and we seem to do that more and more – what is the effect on our imaginations?”

I had suggested that what his work seemed to be concerned with the degree to which we can make people measurable and project ourselves into codifiable form. His humanoid sculptures struck me as projections of recorded dimensions, defined by the flattening of curves into straight lines. “I guess you could say, you’re reinforcing those forces of conformism. And I would say, no, I’m trying to point them out. I’m giving you the instruments by which you become aware of these things.”

He spoke often of “instruments”, both in the press conference and, subsequently, when we sat down together. His works were to function as “diagnostic instruments”, or “instruments for our measure.” The show itself, as a whole, he described as a “test site”. Wasn’t there, I wonder, some contradiction between the scientificity of this language and his other professed wish to inject sculpture with a renewed affectivity, after the strictures of formal modernism.

“But I think that’s the paradox of the thing,” he says. He directs my attention to one of the first works in the show, Mean, a six foot two steel frame of a man, resembling equal parts TV aerial and medieval torture device. “Mean looks at first like the cruellest kind of cipher of a human presence,” he says. “It looks at first like it has absolute bilateral symmetry – but of course it doesn’t. And the degree to which it doesn’t is the degree to which it can begin to transmit something about the individuality and peculiarity of the body which it is a mean or measure of, and indeed the affect of that body.”

“I think of it like an antenna,” he continues. “If you tune into it, you will begin to see things. It will tell you things, both about itself, but also about you. I think that’s the bottom line of my proposal: that art or sculpture, in eschewing representation enforces reflexivity.”

Antony Gormley, BLOCK, 2016, Concrete, 159 3/4 x 158 15/16 x 129 1/16 in. (405.8 x 403.7 x 327.8 cm), © Antony Gormley. Photo © White Cube (Ben Westoby)

Gormley believes that it is possible to escape the ideological associations of “representative” statuary through what he calls (at the press conference), “an objective mapping of a body or a space.” But this very desire recalls the original impulse of the Enlightenment, in Francis Bacon’s call upon the natural sciences to act as an impartial activity working with unchanging laws. Like the enlightened philosophes of the 17th and 18th centuries, Gormley sets out from the standard of his own figure – “only,” he tells me matter-of-factly, “because that’s what you’re given,” – and determines to measure everyone else by its presumed norm. But in the process he becomes alienated from his own body, failing to recognise its uncanny doubles even when brought face-to-face with them. His work powerfully and forcefully enacts the Cartesian split between a body that becomes estranged in its inert materiality and a mind or spirit doomed to mystification by its absolute separation from the physical.

“I want to recognise that I am an other,” he says to me. He calls this recognition the “universal condition of a self.” But as many critics of Enlightenment reason have pointed out over the course of the twentieth century, claims to universality on the part of privileged white, European men have exhibited a tendency to silence and exclude the voices of those others who think and feel in different ways. The light of reason never has diffused equally upon all subjectivities.

Towards the end of our interview, I remark upon the brightness of the gallery where Gormley’s sculptures are exhibited. It struck me as considerably more vividly lit than the Virginia Overton show down the hall in the North Galleries.

“We put in a whole new lighting system,” Gormley confirms, “but most of it is well below it’s hundred percent. Light is an important consideration. I would rather have it naturally lit.”

Earlier, at the press conference, Andrea Schlieker had been speaking on the subject of one of the most physically involving works in the show, Passage, a twelve-metre-long steel tunnel cut to a cross-section of Gormley’s own frame, into which spectators are invited to step, gradually losing themselves as they get deeper and deeper into this road to nowhere. “It’s this notion of the inner darkness,” she said, “which has been such a strong topic and theme for you for a long time.”

On the stage beside her, with thumb and forefinger clenched tightly over his mouth, he said, “forever really.”

Antony Gormley, Fit, is at the White Cube in Bermondsey until 6 November