I am wandering around the Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall, head tipped back, nose in the air twitching like a truffling pig or a rabbit, out on the plains, testing the air for potential threats. After the sensory overload of the walk along the South Bank – a perceptual maelstrom of buskers resonating under stone bridges, wafts of caramelised peanuts and brackish water, the dense visual confusion of old and new architecture, tights crowds of people in garish clothes, coloured lights and flashing signs – entering the Tate’s sloped western entrance always feels like something of a respite. But on this occasion, beyond the guards checking QR coded tickets, the milling punters, the bulk and sweep of the building itself, I seemed on first glance to be confronted with almost nothing. Nothing to see, anyway – at least, not at ground level. The art, here, is all in the air.

Over in the Starr Cinema, before the assembled press, artist Anicka Yi cites reflection on “the air that we inhabit” as a “guiding principle throughout this project.” In particular, she notes, the element of “risk” that this shared lifeworld seems increasingly to imply. According to the philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, the weaponisation of our breathable environment constitutes precisely the “originality” of our past century. From the first gas attack at Ypres in 1915, “a kind of military climatology sprang virtually out of nothing,” Sloterdijk contends. We have been living with the psychic consequences of this “spectacular revelation” ever since. But over the last eighteen months of airborne global pandemic, the conditions of our atmospheric cohabitation have become increasingly fraught.

Ever since the focus of public health messaging around Covid-19 turned from the washing of hands and surfaces towards the mechanics of aerosol dispersion in closed and confined spaces, we have learnt an enhanced wariness towards the air that we breathe and the potential passengers it might bring. We have spent winters sat outside pubs and restaurants, worn masks on the tube, zealously opened windows. Airlines and train operators boast that their onboard atmosphere is completely cleansed and renewed every three minutes.

Yi’s Turbine Hall installation was fully planned and designed before any of this took place. Still, she recalls the panicked expressions of Tate’s curators when she told them of her plans to release her odorous adulterants in the ambience of the Hall, a week-by-week revolving programme of scents fashioned to invoke everything from the pre-human past to a possible machine future.

“Air is this charged site for social and political discourse,” Yi insists. “Every breath that we take, we are inhaling the Earth’s past … We are potentially breathing in atomic nuclei from the ashes of Joan of Arc … We are vessels of interdependence and we have a responsibility to each other.”

Since the olfactory menu is said to be changing from week to week, someone from the parterre had to ask the obvious question: what is it we can smell in there right now?

“Currently we are smelling cholera,” Yi states flatly. “I thought it would be a fun take.” This gets a big laugh from the reporters in the room.

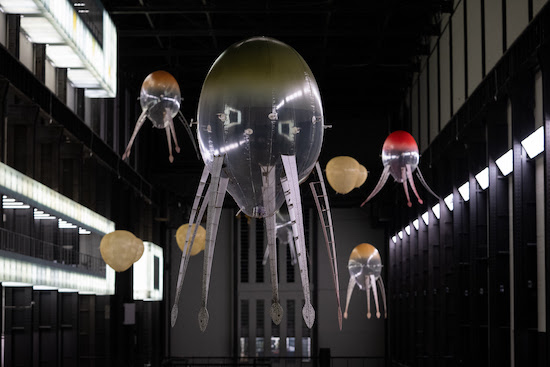

The smell of cholera (or of coal or caraway and cayenne or precambrian life) is not all there is to Yi’s present work. These scents share the air with “an aquarium of machines” called “aerobes”: mechanical medusozoan sculptures with inflatable bodies that bob and drift amongst the building’s rafters, raised by helium and powered by a perimeter of tiny rotor blades. There are giant alien “xenojellies” with flapping quasi-chitinous legs. There are globular “planulae”, like pastel-tinted Ikea lampshades. Apparently this imaginary menagerie can detect human heat, will be drawn towards human sweat, and will “learn” and develop, in some not quite clear sense, over the life of the show.

“Machines don’t necessarily have to serve us or scare us,” Yi says. She tells us of her interest in “wilding” her own machines, to hint at a “more nuanced, complex relationship” with automata than fiction has traditionally offered us.

Still the smell, clearly, is a major element of the work. It’s what Yi is famous for – having infused a book with the odour of “Aliens and Alzheimer’s” in 2015 and brought clouds of B.O. and rotting kombucha to the Guggenheim in 2017. But when I first arrive at the Tate, all I’m smelling is day-old detergent and halitosis, the lingering ghosts of the morning’s breakfast. “Please wear a face covering,” the ‘Plan Your Visit’ page on the gallery’s website continues to implore, “unless you are exempt.”

At the press conference, finally, someone in the audience pipes up and asks the obvious question: Should we take our masks off to experience the exhibition? But the specific query is unfortunately buried by the questioner in a multi-part challenge and Yi deftly sidesteps this bit.

I do, eventually, somewhat guiltily, pull down my mask for a while, determined to inhale what I can of the work. But even as I wander around in search of nebulisers, I’m not getting much more – perhaps a faint whiff of something vaguely perfumed for a brief moment. Something slightly grassy maybe? It comes and goes before I can really grasp it. Smell is elusive. Am I just too congested? Did I catch a touch of that Bad Cold several friends have complained of lately? Or is it just decades of rolled-up cigarettes blunting my sensitivity, leaving me aesthetically ruined for all olfactory art?

Leaving the Tate and heading West, across the Thames and down Piccadilly, my nasal hairs feel quite alive to the saccharine clouds of bubblegummy vape smoke, the fatty fug of freshly fried churros, that I pass along the way. Arriving finally, at the back end of the Royal Academy, I find myself confronted by more aromaesthetics – or, not quite.

Superblue is a new addition to Mayfair’s gallery scene and its inaugural installation is by artist duo A.A. Murakami (Japanese architect Azusa Murakami and British artist Alexander Groves). Silent Fall welcomes visitors into what the press release would have us perceive as an “endless forest”, but actually resembles something more like a water treatment plant or possibly the shower room at Willy Wonka’s Chocolate Factory. Gleaming white tubes extrude from the ground, lazily issuing football-sized soap bubbles that you can touch and feel (thanks to a wooly black glove given out upon entering). If you press or touch too hard, though, the bubbles explode, releasing a cloud of specially designed scents.

Still wearing my mask, I didn’t notice the scents at all on my first go through. Reading about them in the press bumf afterwards, I sneaked in for a second go, mask down, and only then noticed a certain chemical piney odour – less forest glade, more Herbal Essences shower gel.

We are living through something of a boom in odorous artworks, merely confirmed for me by the fact I got to check out two in one morning. Earlier this year, experimental music label Fractal Meat Cuts released a new album by Glaswegian electronic duo Human Heads in two different editions: one, a cassette tape; the other, a printed download code packaged with a small vial of scent. Take a hoof from the little bottle, mixed with the help of Clara Weale from Glasgow’s Library of Olfactive Material, and you get a solvent kick presumably intended to be as evocative of its home city as the field recording of kids chatting shit at the back of the bus that opens the release. Around the same time, Norwegian dark folk group Wardruna issues their Kvitravn album with a vegan candle of soy wax and citronella, imbued with more pine and a hint of sandalwood. Even Alicia Keys put out her own “sage and oat milk” candle. And then, of course, there is Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop candle, marketed as smelling like the actress’s own vagina (a move somewhat pre-empted by Anicka Yi, who released the odour of female genitalia – though not her own – at the Kitchen, New York, back in 2015). Meanwhile, Mauritshuis museum in the Hague presented a show of seventeenth-century Dutch oil paintings accompanied by recreations of the aromas there depicted: the scent of fruit from a still life, or the zing of spices for Willem van Mieris’s A Grocer’s Shop.

“Many philosophers refer to sight;” writes Michel Serres, “few to hearing; fewer still place their trust in the tactile, or olfactory.” Smell has long been rejected sense. For stoic philosophers and medieval monks alike, smell was situated near the bottom of a hierarchy of the senses which placed the supposedly more ‘spiritual’ faculties of sight and hearing at the top. Smell was always too fleshy, too intimate. After spending so much time at home, in isolation, interacting through Zoom calls and group chats, it may be precisely these corporeal qualities that make the sense so appealing in the present moment. After all, you can’t download a smell. But Serres’s solution is not simply to upend the old hierarchy of the senses and place the olfactory at its peak. “No body has ever smelt and smelt only the unique perfume of a rose,” he writes. “The body smells a rose and a thousand surrounding odours at the same time as it touches wool, sees a complex landscape and quivers beneath waves of sound”.