Albert Oehlen, Uurhyolth II-13, 2001, inkjet and mixed media on canvas, 220 x 340 cm / 86 5⁄8 x 133 7⁄8 inches (2 parts) © Albert Oehlen Photo Credit: Courtesy Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris and the artist

Dubbed "the most resourceful abstract painter alive" by the New Yorker, "a master of disciplined excess" by the New York Times, Albert Oehlen’s exuberance has been spilling from the canvas to the streets since the late 70s. A one-time "bad boy" of the Berlin art scene and occasional member of groups The Red Krayola and Van Oehlen, the Krefeld-born painter has parlayed a dizzying dialectic of restraint and abundance, in both life and work, for some four decades now.

A new book from Taschen covers the entire extent of his career with over 400 colour reproductions. The following exchange, between the artist and Hessisches Landesmuseum, Wiesbaden, director, Alexander Klar is an edited extract from the book.

Alexander Klar: I’m interested in something purely practical: How do you approach a picture? How do you start your day?

Albert Oehlen: There are always the pictures that were already there and have turned into something. I am always at some point in the work that is defined by what I’ve already achieved. I know that I have to press more on this tube and less on that. At that level, of course, there are things you have to follow. There are also these altogether everyday things: if I have been dealing with a very large picture, then I may be exhausted, or fed up with it, and I decide that at the moment I don’t want to do another thing that size, and would rather do something smaller. Or vice versa: I’ve discovered something while painting, and think: I must explore this a bit further. To that extent, there’s always a to-do list that can’t be described in grandiose terms, but which results from what you’ve done already. That may just be a technical thing, or maybe you’ve had an idea for a motif which you want to explore a bit further, and then you say: in the next three pictures I’ll tick off that box.

A.K.: Are there particular pictures than float around in your head before you paint them? For example, you go to an exhibition, see something, and suddenly think …

A.O.: Yes, it’s hard to think of an example, but there’s no doubt that happens. You see something, and you say … I don’t know… this hysteria that occurred, I’d like to exploit that for myself, I’d like to profit from it. Then you go and try to realise this idea. But I don’t mean the visual idea that tells me what colour I have to use … For example in the Basel Action Painting exhibition in 2008, something gripped me, though it might seem somewhat banal if I repeated this now … maybe it’s just the word “action,” which would never have occurred to me in respect to my work— it wouldn’t have occurred to me, because when I started abstract painting, it was precisely these ideas that I tackled. That was precisely what there was back then, that was 1960s painting, then there was twenty years peace and quiet, with nothing new, as far as I know. That was history, for example action painting, gestural painting. By contrast, what I had to offer was a well-considered, very slow way of painting, and a very artificial approach which has nothing to do with spontaneity, or aggression, or moods, or drugs or whatever. Everything that played a role in this painting that I wanted to refer to, I wanted quite precisely to have nothing to do with. I wanted to construct the picture. And then I arrived in this exhibition and suddenly see the word “action,” and by reason of what I’d done in the past twenty years, this was then the moment when I could make sense of “action.” By adding it to what I had developed for myself, it was a quite different story from what it would have been if I’d started attacking the canvas with a run-up in 1988.

A.K.: What makes your pictures hard to read is precisely the figural, for example when there are posters there. One wonders: is the gesture now a reaction to the poster, a confrontation with it?

A.O.: The joke is, of course, that actually the conception of the picture aims to be – and hopefully is – the opposite of what one does in words when one talks about pictures. Then, in order to distinguish the pictures one from another, or to make clear which one you’re talking about, one will have to say: The one with the poster or The one with the breasts. It happens however on the contrary that the painting per se asserts itself, that the beginning and end of the picture is the painting and keeps these nameable things under control. If the picture took its character from the foreign bodies within it, it would be a failure, for then they’d be pictures that had been “pimped up.”

A.K.: I don’t see any distinctions there. Some of the pictures have no poster at all, others have very many, but the posters themselves play a subordinate role. It’s the presence of the poster that’s remarkable. That’s what strikes me: in some pictures, I don’t miss the absent posters, in others the poster doesn’t disturb. They are a – relatively – natural component of what one sees.

A.O.: That is possibly a small pointer to the fact I may have succeeded in what I was planning to do. But the understanding I want of these pictures is that the elements should be irritating. Their function is that they are reduced to something formal, but by formal I mean more than what Kandinsky described: how the curve meets the point, the dull the shiny, and the black the white. I extend the concept of the formal to things which in other circumstances we might perhaps call content-related. So if we can now read a very simple word in the picture, as I did for example with these loans from Pop Art … for example in one picture it says “2NITE,” which obviously comes from the Pop text milieu. This is so hackneyed, so one can say a few things about it … of course one can go and ask what tonight means: and what happens tonight? The artist goes to bed. You feel at once, there’s no traction there. What there is, though, is this rather cheap Pop appeal.

A.K.: … simply because tonight is represented as “2NITE”, there’s already a context. Trashy.

A.O.: Yes, as has been explained, it’s a question of not being narrative. I have this vision of being able to introduce something, where you recognize something, and yet it’s not being narrative. That’s precisely my ambition. That something is perceived really as only a whiff. And then I approach these motifs very sensitively, and the terms too that I let into the pictures, exactly because I want to rule out that the pictures tell a story or advertise anything …

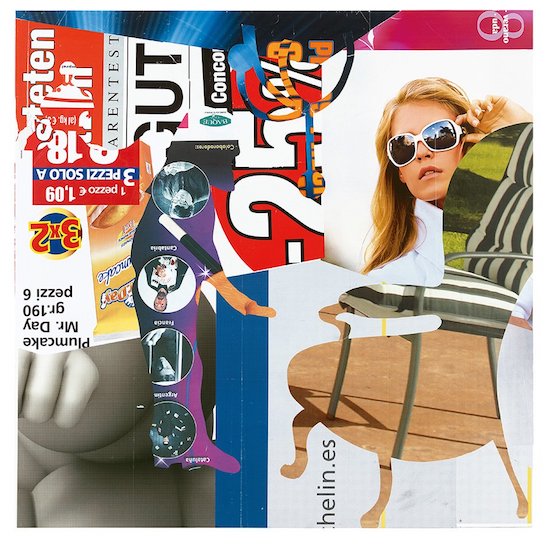

Albert Oehlen, I 12, 2010, paper on canvas , 175 x 175 cm / 68 7⁄8 x 68 7⁄8 inches

© Albert Oehlen Photo Credit: Lothar Schnepf, Köln

A.K.: When we look at the work process, is the first thing you do to stick on the poster or the paper?

A.O.: It has to be that way, the adhesive is water-based and the oil paint comes after. You can’t do it the other way round.

A.K..: But you’ve also painted motifs from posters, I mean, copied them in paint?

A.O..: That was a few years ago, I simply had a desire to work with advertising. I can hardly explain any longer what I wanted to do back then. Maybe it’ll occur to me later.

In any case, I copied some pretty extreme supermarket advertising and then saw what it looked like, and then I destroyed it again, and no sooner had I destroyed it than I realized what I could have done with it. But by then it was too late.

A.K.: That’s harsh …

Albert Oehlen, FM 20, 2008, oil and paper on canvas, 240 x 200 cm / 94 1⁄2 x 78 3⁄4 inches

© Albert Oehlen Photo Credit: Courtesy Galerie Max Hetzler, Berlin | Paris and the artist

A.O.: Advertising is primarily associated with Pop Art. On the other hand, with these décollage things, there you have posters and advertising too and a bit of the trash aspect.

A.K.: And that can be expanded – all the way to consumer critique. But for that we’re twenty-five years too late.

A.O.: Consumer critique is of course a bit stale, as a result of art people have got used to it. On the other hand, advertising hasn’t got any more reticent in the slightest. Rather, when you look at current supermarket advertising, not least in Germany – one could almost say it’s regressed to the former terror level, and that’s now totally normal. There’s another, comical, side aspect, when in art or in its reception the standards sink … But somehow Pop Art has sanctioned trash in advertising.

Albert Oehlen, edited by Hans Werner Holzwarth, Hardcover, 9.8 x 13.1 in., 496 pages, is published by Taschen