250,000 new homes are required to be built each year to keep up with housing demand in England, and in reality we’re not even close. A situation as critical as this requires alternative thinking if it is to turn around, and perhaps looking backwards as well as forwards may provide the answer.

The work of the architect Walter Segal and the communities of self-builders who built their own homes in the 1980s are the subject of the Architectural Association’s fascinating exhibition which takes a behind-the-scenes look at how homes were built by people, who in some cases hadn’t even been able to put up a shelf. With the support of the London borough of Lewisham’s councillors Segal and the self-builders realised somewhat utopian community housing projects that relieved a little pressure on the council’s increasing waiting lists and offered the chance for a few to build a home to their own specification.

In the context of 1980s London, when Thatcher’s Right to Buy policy began to offer low-cost home ownership and by design deplete the council housing stock along the way, at the same time a charismatic German architect was encouraging many Londoners to build for themselves. While these projects were limited in scale they fitted naturally with the home-owning, enterprising citizen that Thatcher was keen to inspire, and gathered support from Labour councillors like those in Lewisham who perceived it as a leg up for working-class people.

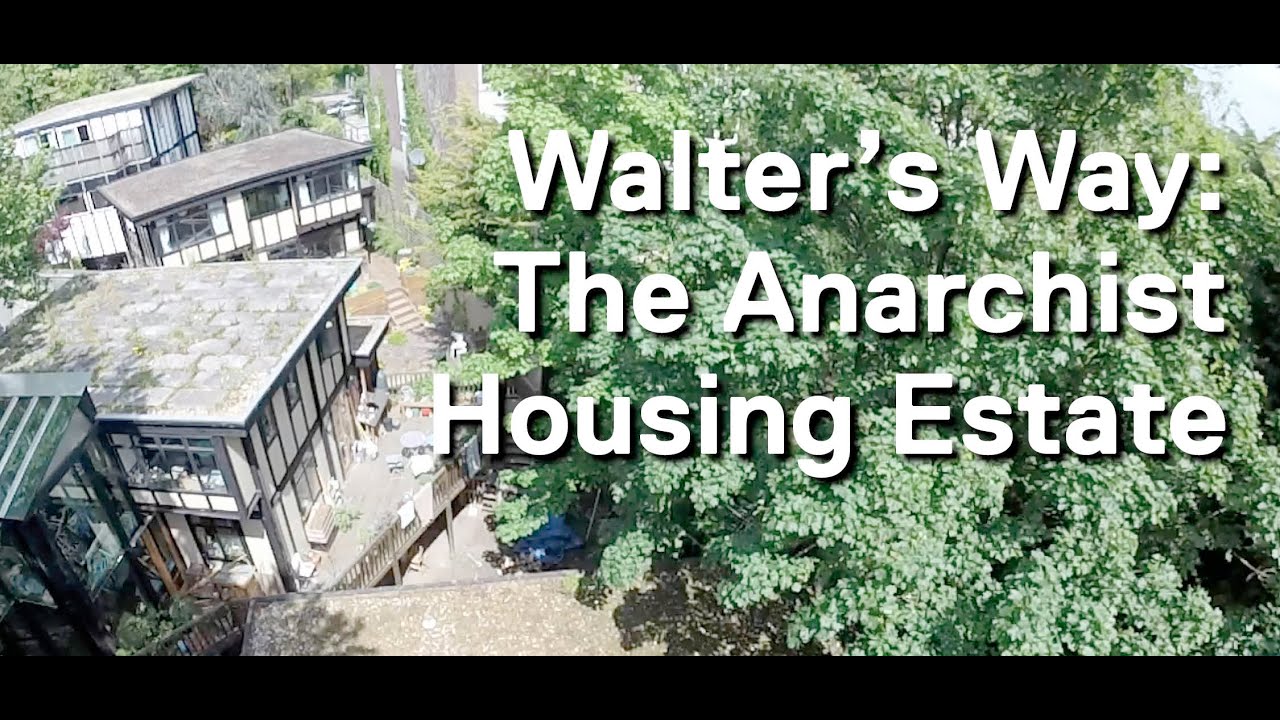

The concept Segal proposed allowed ordinary people with no prior building, design or architecture experience to build without difficulty. Dave Dayes, one of the original self-builders, commented in a video in the exhibition that Segal would say: “all you need to do is to be able to cut a straight line with a saw and drill a straight hole.” This meant that no wet trades like concreting and plastering were needed, just on-the-job learnt skills of woodwork and joinery. Upon a visit to two of the roads in Lewisham council, Walters Way and Segal Close, you can see that some were more adept than others. In fact the differences between each house are noticeable not just for the quality of the finishing but for the fact that Segal designed them to be flexible, to be modified when a particular family’s changing needs demanded it.

I was introduced to these buildings early in my life when my parents were looking to buy their first home in the 1990s. By this time, the original self-builders were beginning to move on and a handful had come on to the property market. The house in Sydenham, South London built under the Segal method was a snip at £30,000, half the amount of regular houses in the area, except no mortgage lender would lend against it. And when my parents found one that would, their surveyor deemed it unfit to live in. Not because of the quality of the house but because the house was built on an underground stream. Except the original councillors knew this, which was why the land was first offered to the self builders, because Segal’s method of using light timber frames meant that construction could occur almost anywhere. Perhaps the greatest reason that councils considered experimenting with this method was because otherwise that land would go unused.

The experience that my parents went through is typical of the mentality that surrounds homebuilding in the UK, where councils and homeowners alike are dismissive if it isn’t a standard brick and block-built house and engineered by a large, recognised developer. Except the current housing situation requires and deserves more progressive thinking.

There are signs that self-building is being considered once again. Notably, the architecture collective Assemble’s Granby Four Streets project in Toxteth, Liverpool, which aided a community land trust of local residents to design, rebuild and preserve the houses that the council earmarked for demolition. The Toxteth project took inspiration from Segal, and many of Assemble’s projects have borrowed from Segal’s timber-framed method of construction, which is recognised in the Architectural Association exhibition by way of a model of another of Assemble’s recent works. It is of a construction they built to replace Segal’s “Little House”, which he built in his Highgate garden in the 1960s and which would go on to become a prototype for the self-builds. The fact that a group of architects like Assemble could win an art award like the Turner Prize for their involvement in the Toxteth community project signals either the continuing cultural relevance of projects of this nature or the shit show that is housing in the UK.

Architects today are still willing to be involved in socially-responsible projects, and a direct legacy of Segal can be found in the Rural Urban Synthesis Society (RUSS), a community land trust in Lewisham chaired by Kareem Dayes, son of Walters Way resident Dave Dayes, which acquired its first piece of land late last year. But for all the work that trusts, co-operatives, architects and councillors are willing to put in to step closer to solving an extreme housing situation it is government inaction that stands in the way.

The writer Owen Hatherley is right to say that it is fanciful that self-build houses is going to solve the UK’s housing crisis. The legacy of Walter Segal and the Lewisham council project isn’t just the 200 or so Segal-inspired self-build houses in the UK and the community land trusts like RUSS which look to increase that number, but that he showed that there are viable alternatives to the housing market that struggles to provide for demand till this day. Whether it’s self-builds, co-operatives, a rejuvenated council housing commitment, conversions of shipping containers, floating homes on the Thames, rental caps, building on the green belt, housing reform that restricts foreign ownership or second homes, or something that hasn’t yet been devised, housing and particularly affordable housing is a problem that requires alternative, and more radical solutions.

Walters Way – The Self Build Revolution runs until March 24th at the Architectural Association gallery, London