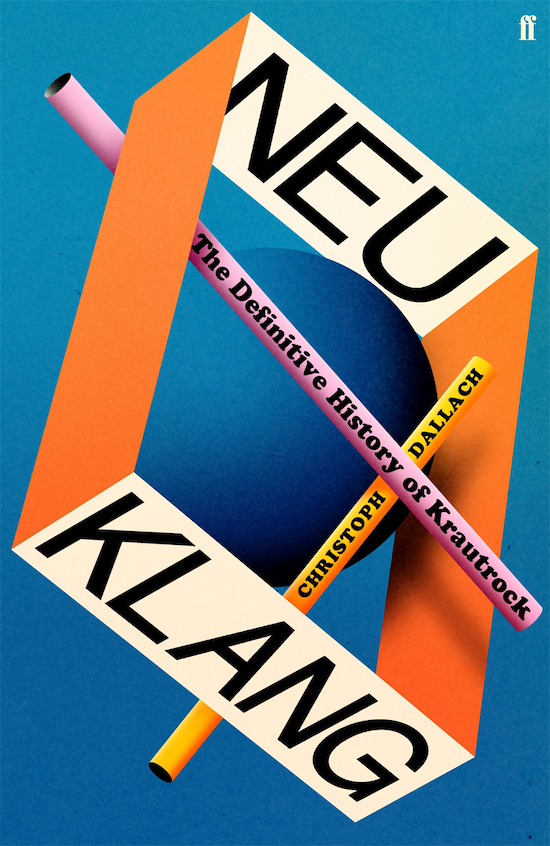

This week Faber publish Neu Klang: The Definitive Story Of Krautrock by Cristoph Dallach, the first comprehensive oral history of the diverse and radical movement in German music during the late 60s and 1970s. Including eye-witness accounts of the rise of groups such as CAN, Neu!, Amon Düül, Popul Vuh, Tangerine Dream, Cluster and Kraftwerk, from the likes of Irmin Schmidt, Jaki Liebezeit, Holger Czukay, Michael Rother, Dieter Moebius, Klaus Schulze, Karl Bartos and Brian Eno.

Author Christoph Dallach and tQ Ed John Doran will discuss the book and the radical history of krautrock at Rough Trade West on May 14, to celebrate its publication.

One of the strangest stories in the field of Krautrock is that of anarchic improvisers Faust who were initially sold to Polydor on the basis they were "the German Beatles" by left wing intellectual Uwe Nettelbeck; the label footed the bill for a period of communal living in a farmhouse in Wümme, near Hamburg – the peace of which was only shattered by the band being mistaken for a terrorist cell and, of course, their noisy jamming in the middle of the night. By their third album Polydor had had enough and pulled the plug, so the band decamped to London where they immediately began courting Richard Branson and his Virgin label…

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: The Faust Tapes were our doorway to Virgin.

SIMON DRAPER: Uwe Nettelbeck told us they had a whole lot of recordings they’d like to release. We responded that we’d prefer fresh recordings made in our own studio. So Nettelbeck suggested just giving us the old recordings, on condition that we didn’t make any money out of them. We came up with the idea of making them into a record that we sold as cheaply as possible. We marketed The Faust Tapes as ‘an album for the price of a single’. The price was forty-nine pence, if I remember rightly. And the record sold fantastically, although I doubt many people liked it – The Faust Tapes was a very challenging, difficult record that was presumably too much for most people. But I loved the idea of it helping Faust to break through.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: Branson agreed to us living in England under the same conditions as in Wümme. That was the Manor Studio, a nice old pile with a great studio and a good team.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: Branson had a studio near Oxford, actually more of a castle, and that’s where we recorded. Mike Oldfield used the studio in the daytime, and we went in at night. He’d made Tubular Bells there all on his own. It wasn’t our bag, though – way too clean.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: Mike Oldfield used to pop in and see us. He loved to sit under the table, barking like a dog. We’d give him a kick but only because he wanted us to; he was a bit mad. Or maybe he just wanted to take the mickey out of us Germans by pretending to be a German shepherd, I don’t know. I didn’t like him much.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: Oldfield was barmy. We’d be sitting there, and Oldfield would get under the table and bite us on the ankles. Once I hit out under the table with a curtain holder and caught him right on the cheek.

SIMON DRAPER: I kept out of the recordings Faust did there. Partly because I was so young, younger than most of the musicians I signed. I loved jazz and was generally into music, but I didn’t have a particular concept that I wanted to suggest to our acts; I was more of a fan. As I got older I did give the artists advice, of course, suggested producers and that kind of thing. But in 1973 I didn’t have the experience to do that, I just trusted that they’d make an effort in the studio. Mike Oldfield did what he liked there as well; he was living there at the time. He’d actually only had a week there to finish off Tubular Bells with our sound engineers, but he just stayed on. He had no fixed abode anyway, and no money. We didn’t intervene, so he just hung out there for longer. The girls who worked there were nice to him.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: We got to know Oldfield in the studio, when no one knew how big he’d end up, but we did pick up on his success building up. Branson was really into Tubular Bells from the beginning, partly because he knew it would sell and make him rich. Then he organised the famous concert at the Queen Elizabeth Hall, mid-1973, when Oldfield played Tubular Bells with this all-star prog orchestra, and he invited all the top acts along – we hung out backstage with Mick Jagger and guys like that. Back then Branson still thought we might wind up as successful racehorses as well.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: Once Mike Oldfield finished Tubular Bells he invited a few musicians over. Keith Richards came in a sports car, and someone drove his Rolls-Royce along after him. We went to the pub later, but I stayed in the Rolls-Royce getting drunk, ended up pretty wasted. Then along came Keith Richards’ bodyguard, dragged me out of the Roller and punched me in the face.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: We weren’t all happy with Virgin Records. The only people I had time for were the team at the Manor Studio and Simon Draper – they did a lot for us.

SIMON DRAPER: We put them in the Manor Studio to record their new album – which I guess wasn’t such a good decision. But it was part of the contract. Then they wrote me a list of everything they thought was ‘Scheisse’. They didn’t even like the flat we’d put them in in London. I was twenty-two at the time, doing my best. I’d have given my right arm to live in a flat like that, but it wasn’t good enough for Faust. They were very quick to pronounce all sorts of things ‘Scheisse’ and they thought they were pretty big stars. At any rate, their demands always outweighed their sales figures.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: Then we started work on Faust IV. It had to be a pop album again. Although it did still sound pretty quirky. Simon Draper would come over and listen to the music. Uwe came too and commented on what we were doing. He had specific ideas as well.

SIMON DRAPER: Despite all the difficulties, Faust were definitely one of a kind. The audience expected something unusual from them. And it got plenty!

STEPHEN MORRIS: The Faust gig I went to when I was sixteen was really very, very odd. It must have been about 1973, in the Manchester Free Trade Hall. I remember they played in total darkness and only did two songs, but it lasted over an hour. The most exciting thing was that they seemed so mysterious, none of them appeared as individuals – the idea of the band as a unit eclipsed everything else.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: You concentrate much differently in the dark, as a band and in the audience.

SIMON DRAPER: Around the time of Faust IV I saw a gig they played, which was one of the most incredible things I’ve ever experienced. They got this guy on stage with a pneumatic hammer, and he was part of a few of their appearances after that. The sound was fantastic, loud enough to drive you out of your mind.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: The idea of the tools on stage was mine. I went for a walk round the block before a gig in Birmingham. There was a building site, and someone was breaking up rocks with a hammer drill. I asked him if he’d like to join in at a concert. He didn’t know what to think at first, thought it was a joke, and then he asked his boss and said yes. That night we got them to heave a rock on stage and cover it with a blanket so no splinters came off. I’d asked the builder to come in his work outfit and arranged that I’d give him a sign when we wanted him to start, and another one to stop. And then, of course, he came in a bow tie and suit because it was a concert, and his mum and granny came along with him. The sign for starting went fine, but not the stop sign. I kept on signalling to him ‘That’s it! Enough!’ but he didn’t even look my way, and he went on hammering away until the end of the gig. The audience loved it. And it was certainly unusual.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: Back then, at any rate, we started bringing industrial sounds on stage, almost ten years before the Neubauten. I was really into the idea of working with cement mixers, I was virtually in love with the cement-machine sound. As luck would have it, I met this French guy who composed contemporary music, at a party in the countryside somewhere. I told him what I did, and he listened closely. In the end I said: ‘Couldn’t you write a concerto for cement mixer and orchestra?’ And he said: ‘Absolutely, something like that needs to be written.’ I was interested in sound symbioses, whether it was cement mixers, coffee machines or knitting needles.

SIMON DRAPER: When they played the Rainbow in London they had TV sets on stage, and it worked like a dream. All the monitors showed an opera singer doing his thing. Henry Cow put on a big show before them – they’d decided to compete with Faust on the actionism front. They’d had ten brass players and dancers who ushered the audience into the hall to make sure everyone saw the support band. Some of the brass guys were pretty well-known British jazz musicians, and later on they parped away wildly at the back of the auditorium. Ray Smith, who’d done all the sock record covers for them, stood around on stage doing his ironing. Fantastic stuff.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: We had welders, sculptors and knitters on stage. My girlfriend’s kids did their homework on stage. They started off shy, looking down at the floor, but when people started clapping they had their fun as well. We wanted our shows to smell like hard work.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: Gunther, Rudolf and I were Dada fans. We did a play as well, called Dr Schwitters, pretty much pure blasphemy actually.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: We started hiring power tools and using them ourselves, that was safer. We did overdo it a bit for a while. On a US tour the stage looked like the aftermath of war after every gig. Everything was destroyed. Sometimes we’d smash up a piano, sometimes there’d be a fire on stage and it’d be soaked in water afterwards. But at the end of the gigs people came up and took the wreckage home with them, sometimes even autographed. We often got banned for life in those places, but it made for good press: ‘Day or Die Faust,’ etc. We’re still banned from the Great American Music Hall in San Francisco.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: People never danced at our gigs. The audience was mostly older intellectual men with beards. Hardly any women.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: What I always wanted was for Faust to break down clichés. We wanted the shows to be as exciting as possible for us, which is selfish, of course. We wanted to be impressed by ourselves on stage. We played in a boxing ring once, in Liverpool.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: Virgin had promised us a huge PA. That’s nothing special these days, but at the time it was really cool for musicians. The PA was supposed to arrive on time for a show at the Rainbow Club in London, but no surprise it didn’t. I decided to go on stage naked, in protest, and the club lowered the curtain instantly. ‘What a scandal!’ The English are a bit prudish. So I got dressed again and we went back on. The end with Virgin came because we had a different live philosophy to Richard Branson. I didn’t pick up on much of it, though. Zappi and I were never into long discussions; either we’d be making music or we’d take the dogs for a walk. Anyway, they had a big palaver and something didn’t work out. Branson apparently had a certain vision for Faust, and Irmler, Rudolf and Nettelbeck had different visions. The upshot was that Irmler and Rudolf hit the road. Gunther, Zappi and I stayed.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: Everyone wants commercial success at some point, it just never worked out for us in the end. But Uwe always made sure we had money. Without a record contract, Faust probably wouldn’t have lasted long.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: It was always a given for us that no one else was allowed a say in our music. At some point, though, Branson and Uwe tried it, which led to the break-up. I fell out with Uwe over it, and I refused to speak anything but Swabian to Branson. Then Faust split up for a while, to give us all a bit of a break.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: Nettelbeck used to come on tour with us at the beginning as tour manager, but then he did other stuff.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: There was a little tour lined up, five or six gigs, and we did them, partly with other musicians like Uli Trepte and Peter Blegvad. But after that tour we jetted back to Germany – and we all met up in München at the Arabella Hotel, where the Rolling Stones were staying as well to record in the Musicland Studio, down in the basement. Our roadie, a Dutchman called Ruud Bosma, booked us in there as well. He was a chameleon who could transform in one second from a roadie to a smart businessman. He went into the Arabella and announced: ‘We’re here with the band Faust from Virgin Records – Tubular Bells, you know. And we want the same studio as the Rolling Stones, for three weeks. Plus rooms for everyone – Virgin’s picking up the tab!’ They just said ‘Sure!’ and let us in.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: After a while we’d had enough of staying at the Manor. We didn’t like the food there any more. So we left and moved into a five-star hotel. We got them to send the bill to Richard Branson, and he even paid it, but then we left the UK and went to the Arabella in München. We spent two weeks recording there and sent the bill to Richard Branson again. He refused to pay that one, though, and the police turned up; two of our parents paid our bail. We paid it back later.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: I’d contacted Giorgio Moroder, who had this studio downstairs at the Arabella Hotel. I asked him what was going on there after 9 pm. Moroder said: ‘Nothing, why?’ ‘Could we record there then?’ ‘Yeah, why not?’ Moroder’s an adventurer too. He had Donna Summer in there during the day, and Faust came in at night. We had a deal with Moroder that we’d pay something as soon as the songs we recorded there brought in some money. I tried to get Branson to cover the hotel costs, at least, but he refused. Still, we had a wonderful time in Moroder’s studio.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: So we recorded there, and after a while the bill got so expensive that the people at the hotel checked with Virgin if they’d really pay for everything. Virgin acted all surprised and said they’d chucked us out ages ago.

SIMON DRAPER: They just had unrealistic expectations. We liked Faust IV as an album, but then they just buggered off and did more recording in München without consulting us. They ran up horrendous studio costs there and then they called us up and asked if we’d pay the bill. We said no, and I’m afraid we had to tell them: ‘Guys, you’re not selling many records and dealing with you’s not much fun, so we don’t want any more stuff from you.’

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: The hotel threatened to put us in jail, and one of us got in the car with the PA and all the tapes and crashed out through the underground car park barrier. The others hot-footed it as well and only three of us stayed: Irmler, Sosna and me. We let them arrest us – at least we’d saved our PA and the material.

SIMON DRAPER: I can tell you with absolute certainty that we never made any money out of Faust’s records. Whether we broke even on the tours I don’t know, but I doubt it. Tours cost a lot and there’s not usually much left over in the end. Virgin definitely sponsored Faust’s tours – that’s why Henry Cow played support, another one of our bands.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: Faust split up then, to let things settle for a while.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: After that we officially went underground. Six days in prison, and then it was obvious we’d go our separate ways. We didn’t fight, we just broke up.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: After the Arabella, we didn’t do anything with Faust for ten years.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: I don’t like talking about that time. Not because I’ve got anything to hide, but it’s part of our legend. Let’s just say that our musical life continued perfectly normally. We just went back to our roots, back to square one, back to Hamburg to the Toulouse Lautrec Institut. Zero hour.

WERNER ‘ZAPPI’ DIERMAIER: A few years ago there was a huge long queue after a show in China, all the way out to the street. They had piles of Faust records with them to get them signed, and we spent two hours giving autographs.

HANS-JOACHIM IRMLER: Faust always had a better reception abroad than in Germany. No one’s interested in us here to this day, actually. We’ll probably all have to die first before anyone in Germany takes an interest.

JEAN-HERVÉ PERON: I don’t see Faust purely as a music band – we’re simply not good enough musically for that. But there are other things we’re pretty good at. Not many people come out of a Faust show saying they had a dull time. Even if you say: ‘That was a heap of shit.’ Most people leave with stars in their eyes.