Imagine if, on that day in late 1993 when you’d first been smacked around the brain by the Wu-Tang Clan’s world-changing debut album, you’d been given half a minute to pick out the group member whose eventual solo discography would stand head and shoulders above the rest. Now think again. Because even Dr Strange wouldn’t have been able to find one story among eight million that would bring you to what, over a quarter of a century on, stands revealed as the only correct answer.

Ghostface Killah was great on Enter The Wu-Tang, but so was everyone else. What we couldn’t have foreseen back then was that his career – a make-it-up-as-it-goes-along dawdle, overflowing with haphazard invention and playful glory – would end up generating one of the most substantial, most fascinating, most compelling and most jaw-droppingly original discographies not just among his Clan bandmates but in hip hop history full stop.

He didn’t obviously have the eye-catching charisma of ODB, clearly wasn’t a leader in the mould of Rza, and he wasn’t blessed with quite the same ability to unify a song with an inspired hook like the band’s rock star, Meth (he’s come close on several occasions, but doesn’t do it as often). His lyrics lack the furious, methodical focus of a Gza or a Masta Killa, he didn’t become the go-to lead-off emcee like Deck, and he never quite seized the chance to dominate a Clan album in the way U-God did with 8 Diagrams. His solo career was so closely intertwined with Raekwon’s (and, to an only slightly lesser extent, Cappadonna’s) that he risked being overshadowed even on his own albums. Yet it’s probably going to be Ghostface’s catalogue that you’d take with you to the desert island if Lauren Laverne ever told you you’d only be able to listen to one Clan member’s records again.

Over three decades of pushing out the boundaries that define the term "idiosyncratic", Ghostface has pulled off the seemingly impossible. He has an eye for detail and a flair for the absurd or surreal, and has found a way to synthesise them. On the one side sits his hyper-realist rap reportage approach, while on the other he throws around free-associative lyrical non-sequiturs. It’s not just that he’s mastered both modes, but how he is able to switch between them not only on the same album but within the same verse of a song, yet somehow never leaving the listener lost, gasping for breath in his wake. This is unprecedented, and he keeps doing it, again and again and again; we’ve become so used to it it’s like we barely notice any more, such that his more recent LPs, whether conventionally solo albums such as 36 Seasons or his most recent release, 2019’s Ghostface Killahs, or collaborations with producers Apollo Brown, Adrian Yongue, jazz outfit BadBadNotGood or Inspectah Deck’s supergroup Czarface, have made far less of an impression than their contents merit.

The slipshod approach to career curation is a problem, yet his apparent disinterest in playing the promotional game is a part of what gives any new Ghost record its singular charm. And it’s not as if he’s totally averse to random acts of wanton self-promotion, though these have been fittingly and chaotically on-brand, such as the 2005 TV series and 2007 self-help picture book, The World According To Pretty Toney (including such all-caps pearls as "SURVEY SAYS, YOUR WIZ MUST WAIT AT LEAST 8 MONTHS BEFORE SHE CAN TAKE A DUMP AT YOUR HOUSE" and "Y’ALL SMART DUMB CATS NEED TO WISEN UP!") or his latest business venture, Killah Koffee, where you can mail-order some Supreme Dark Roast ("this is a variable product") and a Coffee Rules Everything Around Me airtight canister to keep it in. But his discography is, indubitably, a mess.

Ghost’s solo career got off to a complicated and presentationally uncertain start, something which it never completely recovered from, but which may well have helped imbue the following records with beneficial layers of intrigue, individuality and mystique. Perhaps it was understandable, given the considerable creative and commercial success of Only Built 4 Cuban Linx, that Epic/Razor Sharp – a new subsidiary set up to release Ghost’s music, by a major with little experience of the hip hop marketplace, and which only ever released GFK and Cappadonna records (and a couple of compilations) – would present Iron Man as a follow-up to Raekwon’s debut. But having Ghost share the billing with Rae and Cap (all three are equally prominent on the sleeve, and the latter two have supporting-actor-type credits on the front cover) served to undermine his role on his own solo debut. The fantastic original attempt at ‘Box In Hand’ was all over rap radio for months before Iron Man‘s release but the version that appeared on the album was a completely different song, the first in an extended sequence of hits-that-should-have-been consigned to the farthest flung margins of the mixtape/MP3 multiverse. Later, Ghost would talk of how he made his solo debut amid a two-year period of depression, a condition deepened when he was diagnosed with diabetes. For all the title’s intimations of indomitability, the reality was very different.

The magnificent follow-up, Supreme Clientele, boasts 21 cuts on the CD – but only 14 songs are listed on the back cover, the skits only acknowledged on the inside of the booklet. And even this doesn’t tell the full story, a late decision to rejig the track list not being communicated in a timely enough manner to prevent the Canadian pressing plant releasing a version in that territory differs in several minor ways and one major one – it includes the Dramatics-featuring and -sampling ‘In The Rain (Wise)’, itself a bowdlerised version of an early draft of the same song, both of which completists will need to track down online or via one of the plethora of bootlegs that arguably push Ghost into Bob Dylan territory in terms of the vast amounts of unofficial releases of his that are out there. So evidently uncertain were the label about who they’d signed, how best to market and promote him, even what they were supposed to do with the tapes he turned in from the studio, that by the time of Bulletproof Wallets – another "solo" record where Ghost shared front-cover billing with Rae – everyone seemed to have given up: the version sent out for review included two tracks that didn’t appear on the finished LP, didn’t include four tracks that did, and swathes of the rest were presented in different versions. The track listing on the CD cover is an exercise in bet-hedging, with one of the excised tracks included and only two of the four new ones mentioned. It would be embarrassing were this all not so utterly in keeping with the endearingly, indeed often incredibly exciting, degree of sloppiness that characterises Ghost’s work.

So the already long-suffering fan who’d fought their way through the thicket of misinformation, misrepresentation, mischaracterisation and misdirection yet remained convinced of Ghost’s peculiar genius would have been – to nick a notion from Noreaga that feels apt for its blend of clear visual imagery and almost psychedelic oddness – running laps around the English Channel at the news that Def Jam had signed the shape-shifting rap superhero. Sadly, though, the Def Jam of 2004 wasn’t the same label that brought LL Cool J, the Beastie Boys and Public Enemy to the world in the late 1980s, becoming synonymous with formally and creatively progressive hip hop. Although headed by a major figure in hip hop history, the imprint was busy becoming a soul-pop powerhouse. The following year, Jay-Z would sign 20-something R&B singer Ne-Yo and a teenage Bajan pop-reggae prodigy by the name of Robyn Rihanna Fenty to the label and the focus within the company would shift decisively to a hip hop-inflected pop-soul future. Whatever the actual declared or envisioned intentions behind their signings, both Ghostface and his fellow 04-05 Def Jam arrivals The Roots ended up looking an awful lot like lip-service additions to the roster: there mainly to provide proof that Def Jam was still serious about real hip hop. Back then these were arguably the two artists who best represented the magpie music’s unquenchable aspiration to combine integrity, authenticity, individuality and creativity – and having them on the label made it look like Def Jam wasn’t just there to cash in, but wanted to play an ongoing part in showcasing and promoting hip hop as a progressive art form. That the label no longer had the slightest idea how to sell the kinds of records either artist would go on to make only became obvious an uncomfortable period further down the line.

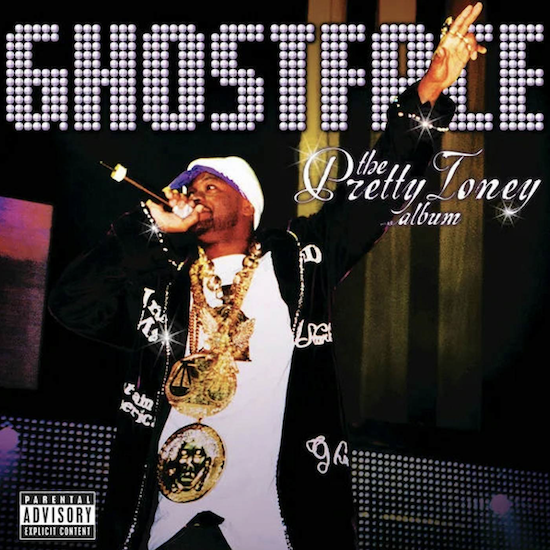

The Pretty Toney Album is nominally the fourth solo Ghost LP, though only the second he was given full and unambiguous one-man credit on, and the only one of what appears to be, at the time of writing, a 20-plus album career (if you include the Theodore Unit album, the CD/DVD double-header with Trife called Put It On The Line, and a series of seemingly fully legitimate, often DJ-helmed, mixtapes) to be released under the truncated name Ghostface. Inevitably, the record that was released wasn’t the one he set out to make, and, with several of the outtakes being bootlegged shortly before and after the April 2004 release date, hardcore fans were once again left feeling let down by comparing the finished version with what might have been. But it is the record on which we got to hear clearly for the first time who Ghost was, is, and was going to become.

Just as its three predecessors may have been great despite the lamentable sabotage they were subject to during the manufacturing phase, so The Pretty Toney Album is a gem where the flaws arguably help make it dazzle. True, ‘Tush’, a collaboration with Missy Elliot, finds both these most idiosyncratic of artists being shoehorned into a rather early-00s-mainstream-rap-by-numbers puffa jacket of a song that neither seems particularly excited about it, even though their performances aren’t lacking in either conceptualisation or effort. There are, as before and as would remain the norm after, several skits which offer a degree of entertainment the first time you hear them but become at best irritating and at worst offputting on further exposure, making the whole thing a more wearying listen than it needed to be. And, of course – Exhibit One for the prosecution in the case that’s been developed over the years to argue against this as being one of Ghost’s better LPs – there’s no appearances from any other Wu-Tangers on the mic, the first time that had happened on a solo LP from any of the group’s members, and a legitimate source of angst for those who had come to expect, and to adore, GFK’s interplay with Raekwon in particular. But despite these reservations, and indeed perhaps particularly because of that last one, this is arguably Ghost’s first truly solo album, marking the first time, perhaps, where we were given a glimpse of who he really thought he was, and wanted to be.

The sound of the record bears similarities to previous Ghost and Wu releases – it’s clearly cut from similar sample-based cloth – but strikes out in a subtly but significantly singular direction. Rza produces only two tracks – one a slightly extended skit, the other (‘Run’) which would also turn up on Cappadonna’s debut album – and True Mathematics one. The remainder come from outside the Wu camp, with the exceptions of ‘Save Me Dear’ and ‘Holla’, which are credited to Ghost himself. Nottz, Dub Dot Z, No ID, Money Boss Players’ Minnesota and Emile, fresh from co-producing some Obie Trice tracks with Eminem, were all either briefed by Ghost to bring him their most soulful beats, or he picked the ones from their beat tapes that cleaved most strongly to the early 70s sounds that he grew up with. This didn’t seem all that remarkable at the time: Rza had dug deep from the Hi Records vaults already, Al Green and Willie Mitchell loops fuelling umpteen Wu classics as the group enacted their first five-year plan. But here, Ghost isn’t finding the acerbic or on-edge elements and building eerie and disturbing tracks out of them: he’s diving into the soul mines and coming back with smooth jams, string-drenched melodies and sung hooks. This was no accident.

"I’m a soul baby," he told me during a brief but vividly memorable encounter in the lobby of a budget west London hotel during the summer of 2004, Ghost resplendent in a New York Rangers baseball cap, red Wu-branded sweatbands, neck chain featuring a massive bejewelled Virgin Mary, and the full-length white bathrobe that had been his sartorial signature since Rae first told him about Genovese crime family boss Vincent "The Chin" Gigante turning up to a court hearing in his dressing gown as part of a years-long bid to demonstrate mental impairment. When asked what music featured in his current listening, instead of current hip hop or even breakbeat-ready 60s funk artists Ghost listed a slew of early 70s soul stars: the Delfonics, the Stylistics, Blue Magic, Curtis Mayfield. "If I was born back in those days I probably woulda been a singer and doing the same thing that they did," he said. "And soul music is what I am right now, to the rap game. You know?"

Indeed we do, and listening to The Pretty Toney Album makes this unignorable. Despite ‘Tush’ and Digga’s polished, precision-tooled track for the celebratory ‘Ghostface’, the predominant vibe is sharp-suited, strategically emotive early 70s soul. Even the steel-toe-cap toughness of ‘Metal Lungies’ is powered by a piece of sophisticated protest soul performed by the Southern Christian Leadership Conference’s Operation Breadbasket Choir and Orchestra. But it’s on the two tracks he produced for himself where Ghost let himself finally and exuberantly off normality’s leash. ‘Save Me Dear’ uses the same Freddie Scott tune – ‘(You) Got What I Need’ – that Biz Markie had turned into ‘Just A Friend’ in 1989. Ghost overlays it with the deathless drums from the live version of Mountain’s ‘Long Red’ and, avoiding using the hook Biz had re-sung or the piano intro he’d lifted, instead goes for Scott’s verse. Yet, in a decisive break with hip hop’s by-then near 30-year orthodoxy, he raps not over a carefully pieced-together selection of those parts of the song that Scott doesn’t sing on, but just slathers his lyrics on top of the original 45 – singing and all. Hearing it in 2004 was the hip hop equivalent of a bomb going off, or of Ghost doing a Christ-in-the-temple scene, upending the incumbents’ tables, shoving the fakes and the frauds out the door. Suddenly, everything that had seemed inviolable or sacred was no longer a barrier – anything was possible, if you were prepared to risk the inevitable ridicule. Hip hop’s promise – made right back in the early days under Kool Herc’s apartment building and out in the parks across New York’s boroughs – was suddenly back at the art form’s centre. If you had the combination of imagination, talent, gall and verve, you could turn old records into new ones. Forget the crisp sheen that Dre ushered in on The Chronic or the high-gloss version of breakbeats that the Bad Boy label had taken to the top of the globe’s pop charts: all you needed was a record that spoke to you, something you wanted to say, and a compellingly original way of saying it. And just as you’re recovering from that seismic shockwave, along comes ‘Holla’, which performs the same trick, only more so – Ghost rap/cry/singing over not just some parts of, but the whole of The Delfonics’ ‘La La Means I Love You’.

This is something he had been trying to do throughout his career to this point. ‘Holla’, he told me, had been around since the Iron Man days and was in contention for that record at one point in its difficult gestation. The original version of ‘In The Rain (Wise)’ followed the same format, with The Dramatics’ 1971 single as its musical bedrock. Everything has to find its time, he said, but admitted to a degree of uncertainty about how this approach would be received.

"I was kinda like, you know, little nervous at the time back then," he said, referring to when he first attempted ‘Holla’ in 1996. "The way I do it’s got to be that emotion. Sometimes I had to practise to get up in that mutha like that. I had to keep on saying it and saying it. When I wrote it, you know, like when I did ‘I Can’t Go To Sleep’, I coulda did it more better. But we had to get it done. So I was just really practising that style; I was still practising, you know what I mean? So, like now, when I hear it, I could have sung it ten times way more better."

Another one with a similar approach was dropped from Pretty Toney – bootlegged or compiled on mixtapes over the years under the titles ‘Beatles’, ‘Black Cream’ and ‘My Guitar’, it used most of jazz guitarist Jimmy Ponder’s 1974 instrumental cover of ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’, but, according to Ghost, Def Jam baulked at paying the $100,000 quoted to clear the sample. (The idea proved to be one that was too good to let go of: on the Clan’s 2007 album 8 Diagrams it was the seed that grew into the lavish ‘The Heart Gently Weeps’, with guitar parts played by the late George Harrison’s son, Dhani, and Red Hot Chili Peppers’ John Frusciante, a hook sung by Erykah Badu, and strings arranged by RZA. Ghost wasn’t the only member to rhyme on it but at least he didn’t get thrown off his own concept.)

As he hinted in our conversation, he wasn’t done with this most extreme yet most simple approach to making a hip hop record. ‘Big Girl’, from Ghost’s second Def Jam album, and arguably his masterpiece, Fish Scale, uses The Stylistics’ ‘You’re A Big Girl Now’ while ‘Supa GFK’, on The Big Doe Rehab, performs the same trick with Johnny Guitar Watson’s ‘Superman Lover’. We might as well lob in More Fish‘s ‘You Know I’m No Good’, ostensibly a remix of the Amy Winehouse single, perhaps also describable as a duet, but really more of a duel – like a hip hop/soul Shane and Kirsty, the pair sound as if they’re sparring, Ghost’s increasingly unhinged performance providing an arresting, almost alarming contrast to Winehouse’s study in lacerating resignation and recrimination. Ghost’s version removes her vocals for the second half of her verses but his lyrics only fill in those spaces, emphasising the sense of a dialogue rather than a guest appearance appended to an earlier, separate take.

Nobody was making records like this back then; nobody is making them like this today. It’s not hard to guess why others have not followed him. Ghost was willing to risk ridicule in order to suffuse his music with emotions that, in other hands, might have come across as overly affected or put on, but from him just felt real. Songs like ‘I Can’t Go To Sleep’ which appeared on the third Clan album, The W, and found him sing-rapping over hefty chunks of Isaac Hayes’ reading of ‘Walk On By’, and his debut’s most open-hearted moment, the hymn to his mother, ‘All That I Got Is You’, opened that door. These songs removed the barricade that prevented all those ‘keepin’ it real’ rap stars from allowing their audience a glimpse of their own moments of emotional fragility or self-doubt, paving the way for a more reflective strain of writing in rap. But in his whole-song-sample tracks, Ghost didn’t just upend convention about what could be considered viable raw materials for a hip hop song – by patterning his flow on the soul singers his parents bought records by, and adapting his delivery to echo their emoting, he sung-rapped his way into listeners’ hearts in ways other rappers would never be able to match. There aren’t many willing to show those sides of their personality today: back then, I suggested to him, there were barely half a dozen rappers who you sensed felt comfortable expressing real emotions on record. Why do they need to maintain this icy front?

"Because, it might be, sometimes people don’t wanna have to let they feelings go," he suggested. "They might be too tough for it, or think they too tough for it – or illmatic, that’s that state. The other side of…" He drifted off for a moment, lost in the thought.

Some of them, I suggested, are probably scared to.

"Yeah. Exactly. They might look on me as a sucker," he said. "But you should say how you really feel, man! If you’re tired of things, if you want God to help, just say it! ‘Please help me, please God, please lord, I love you so much – I don’t know which way I’m going but could you guide me and let me go in that direction, man, where, you know, you can let me see again? If you could just take the curtains over my eyes and just open my way, please! I don’t know how to go in!’ And that’s what I wanna do."