"I was losing it. I’d lost it. I felt the world was against me. It was getting ridiculous. Out of control. I felt hysterical all the time. I was having a psychotic episode, and everyone around me was dreading what I might do next."

Marc Almond – Tainted Life

"This Last Night In Sodom was the sound of two people who’d taken too much of everything and lost control."

Dave Ball – Electronic Boy

On the flipside of Soft Cell’s ‘Torch’, issued 7 May 1982, the fabulous ‘Insecure Me’ asked the listener to consider if "the hand that holds the whip" was not their own. As Marc Almond stared at a story concerning himself in the Evening Standard the following year, he may have had pause to ask himself the very same question. The story concerned him storming into Record Mirror’s Long Acre offices, approaching the writer Jim Reid at his desk while brandishing a bullwhip. Reid’s drubbing of Marc and the Mambas’ recently released Torment And Toreros had been the final straw. Almond was overworked, his fitful creativity spinning in myriad directions. He was stressed out by tabloid scrutiny and ‘superfans’ constantly ringing his Soho doorbell, his patience worn thinner by the ingestion of too much speed. He had finally snapped.

Horrified by what he read in the newspaper he responded by drafting a panic-stricken retirement letter, detailing how "confused and unhappy" he was with both the music business, and himself; seeing himself as adrift from "the person I really am" and "feeling I’m losing my soul". He declared the next Soft Cell album This Last Night In Sodom would be their last. Reports of Soft Cell’s dramatic, imminent retirement spread like wildfire across the press, reaching his oblivious partner Dave Ball via record label Some Bizzare. The following week in a piece for pop magazine, No. 1, entitled ‘My Exciting Future’, Almond walked things back slightly. Bored with media exposure, he said, and seeing himself "dissected into little pieces on the page" he also knew, "in my heart I couldn’t give up singing. Since last Friday it’s been like a funeral. I’ve felt like Meg Richardson sailing away on Crossroads!"

Within weeks a new Soft Cell 7-inch hit record shelves. ‘Soul Inside’ positively revelled in the drama and chaos, Almond on a cliff’s edge while Ball pounded at the keyboards frantically. Emotions were explosive and mixed, a torrent of no-fucks-left-to-give abandon, existential despair and heroically defiant survival instincts in four and a half minutes. The epic 12-inch maximized melodrama, replete with gongs, drumscapes and multi-tracked Marcs hollering into the abyss. The wind machine-heavy, Tim Pope-directed promo video referenced many of the scandals that had engulfed the group, including Almond and manager/ record boss/ accomplice Stevo’s recent trip to the Phonogram offices. The label had decided to double pack the uncompromising ode to casual gay sex ‘Numbers’ with a free copy of ‘Tainted Love’ in an attempt to make it chart; after seeing this the pair rampaged through the label offices, setting off fire extinguishers and smashing platinum, gold and silver discs adorning the walls. ‘Soul Inside’s wild, glorious self-sabotaging pop crept up to 16, higher than any of The Art Of Falling Apart’s singles. Sat atop the top spot for six weeks was Culture Club’s ‘Karma Chameleon’. In an age where everything was going pop, with Soft Cell’s outsider siblings The Cure (‘The Lovecats’) and The Banshees (‘Dear Prudence’) poised for top ten success, the duo had emerged as the real goth & roll rebels. As Boy George bitchily quipped, "Marc Almond is for people who wear black and hate their parents." More than ever they resembled an English Suicide, even covering ‘Ghost Rider’, with Clint Ruin, aka Jim Thirlwell of Foetus.

Of all the pop acts that proliferated in the early 80s, it was Soft Cell who retained punk’s sharp, provocative edges. But extra-curricular activities during the creation of This Last Night In Sodom revealed just how far from the mainstream they’d ventured. Released in November, Dave Ball’s solo album In Strict Tempo featured contributions from Genesis P-Orridge and Gavin Friday. Equally outré were Almonds NYC gigs with Nick Cave, Lydia Lunch and Thirlwell under The Immaculate Consumptive banner.

Never ones to shy away from the dark side, This Last Night In Sodom would be a full-on plunge into the forbidden. Staying in London, avoiding NYC’s multiple nocturnal distractions, they recorded at Trident in Soho, and Wessex Sound and at Pink Floyd’s Britannia Row in Islington. Inspired by Phil Spector, much of it was recorded in mono, a one-channel vortex intensifying Sodom’s claustrophobic variety. At its core, Almond said, was "a mix of dirty R and B and our punk roots" but around this swirled gothic torch songs, dark psychedelia, industrial clangour and twisted synth pop. Ball’s Hammond B3 organ and Leslie cabinet also provided a link to original 60s garage-punk.

A new addition to his synth arsenal was the PPG Wave 2.2, a digital/analogue wavetable hybrid with a high price tag of £4,000. Fleshing out the hi-tech electronics were real bass, guitar and percussion, Gary Barnacle adding wheezing and chugging sax. Supplying backing vocals was Gini Hewes, part of the Venomettes string section heard on Torment And Toreros, who’d marry Ball in January 1984. Former producer Mike Thorne felt The Art Of Falling Apart had strayed too far from Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret’s winning formula, yet Almond had felt that it was still "too lush-sounding". This time there would be no compromises as they seized the reins themselves and proceeded DIY punk-style, Ball especially eager to flex his production muscles.

Drugs fuelled the sessions. Ball later said he was "consuming vast quantities of coke and speed", while Almond’s amphetamine diet was obvious from opener ‘Mr Self Destruct’s reference to "shooting the A". Despite the disarray, the singer told Smash Hits, January 1984 that in the studio, "the chemistry and sparkle" remained intact. Nevertheless he felt fidgety recording, convinced the songs only came alive onstage bathing in waves of frenzied, sweat-soaked adoration from the crowd. Ball, however, frustrated by Soft Cell’s live sound, immersed himself in studio process.

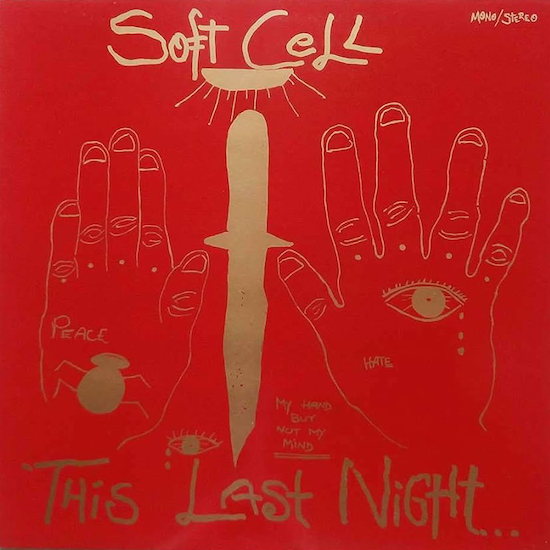

In February, ‘Down In The Subway’ was issued, a cover of grand guignol rock & roll from the ‘Great Balls Of Fire’ co-writer, Jack Hammer. A suicide letter to a cold-hearted, red-blooded baby, the sorrowful saga of "jumping on the train tracks" fitting snugly into Soft Cell’s world. There was little press for Sodom when it emerged on 28 March, perhaps in part because Almond and Ball weren’t on the cover. Instead the singer had found an illustration in a book on mental illness, drawn by a psychotic schizophrenic, depicting two hands, one inscribed with the word "peace", the other with "war", a dagger dangling ominously in between with "my hand but not my mind" scrawled by its tip. Almond, working with designer Huw Feather saturated the drawing in red and gold, apparently to emulate Bournville Chocolate packaging. The pop art touch made the final result darkly exotic, and the album slid more easily into the goth record collections of 1984 next to the Banshees’ Hyaena and The Cure’s The Top than next to that year’s blockbuster pop.

It was an extreme visualisation of Soft Cell’s self-destructive urges, of Sodom’s mood swings. But it also reflected Thatcher’s ‘new Britain’, as its contradictions were central to Sodom, Almond seeing it as both "dangerously hard-hearted and hypocritically moral". He added that "the album title was intended as an apocalyptic statement to suggest that this was our final night of freedom before the impending catastrophe. God, in this case, was substituted by Thatcher." Soft Cell’s close ties to NYC meant that Almond had heard of AIDS ravaging the US gay community early on (‘Down In The Subway’s non-album b-side was called ‘Disease And Desire’). As Frankie and hi-NRG took horny, homo-hedonism into the charts, Sodom was like grim prophecy, warning of the backlash that would ensue once AIDS became mainstreams UK news.

It’s now widely held that Sodom’s reviews were mixed but the pop magazines were enthusiastic. "Soft Cell go out with a bang", wrote Smash Hits’ Neil Tennant, himself just weeks away from the release of Pet Shop Boy’s first single, ‘West End Girls’. He praised "songs about sin, squalor, suffering" on a "hot rockin’ collection" with "luscious Spanish sensuousness, hot and revengeful, richly textured synthesizers and twangy guitar", concluding that it was "a triumphant farewell". No.1 agreed hailing it as "dense, intense and atmospheric, an impressive affair". The NME were less effusive, with Paul Morley, smug from Frankie mega-success, calling it a "shambles", ending his review with a graceless "piss off, Soft Cell".

Far from being an impenetrable mess, Sodom was a masterpiece of taut, frenzied cohesion though. Opening with ‘Mr Self Destruct’, a stomping Tamla-Motown beat is overlaid with impudent punk nihilism, an amphetamine rush of auto-destructive autobiography concerning "building your life up and smashing it down". As it hurtles forwards, Ball’s organ flashes back to his Northern Soul past at the Blackpool Casino, while present day pop is no doubt the target of that "sick of the slick" line, echoed by Almond in Smash Hits in January 1984: "I always wanted Soft Cell to be an antidote to the slick sickness perpetrated by a lot of modern groups, the charts at the moment are back at 1975. Real, sterile, unimaginative, government music with no real subversiveness or riskiness or anything ragged around the edges."

‘Slave To This’ follows, pulverising, punishing and industrial. Over relentlessly pounding drums and deep, growling bass Almond spews out "fear, threat and filth", a troubled mind and a sick world stuck in a feedback loop. Almond’s vocals summon up grotesque images in a multi-layered assault, a nightmarish phantasmagoria of echo-laden, garbled angst about being "sick and tired", "used and abused". Reality is distorted, fractured, broken down into Burroughs-ian cut-ups ("cold-hearted sperm murder"), sent frantically spinning into a kaleidoscope pattern. Adding to the cacophony are sampled, indecipherable voices, incessant, nerve shredding, like a detuned TV that can’t be switched off. Sickening thrills come with Scott Walker-esque croons and chants of "that’s right" as if Almond’s scrambling to remember Mud’s ‘Tiger Feet’. By the end he’s turned preacher, decrying a tearless response to a crucified Christ, exposing the spiritual poverty in weaponised religion. This is the raging id of the 80s; the experience of Almond seeing himself become fodder in Murdoch’s media machine of "slob culture" as the fake, snake oil salesman piety of televangelists triumphs.

While the once cherubic Depeche Mode were tackling issues regarding faith themselves by 1984 (‘Blasphemous Rumours’) and turbo-charging their own version of Soft Cell’s "perv-pop" (‘Master And Servant’), Soft Cell’s ‘Slave To This’ dark electronic delerium was closer in vibe to Mode label-mates Fad Gadget, who were also bowing out that year with Gag, or Coil’s Scatology. Sodom was a building block towards an industrial future, its opener’s title lifted by Nine Inch Nails for their own track, ‘Mr Self Destruct’, a decade later. Following on, ‘Little Rough Rhinestone’ initially feels like a leap from the shadows, bejewelled with pretty melody and bell-like sparkle. With equal parts psych-pop whimsy and goth teen angst, the atomised beat recalls Joy Division’s ‘She’s Lost Control’, while the little boy lost dreaminess recalling Robert Smith soon reveals the hard-hitting sorrow, buried deep in "frightened little eyes". There’s a gaping absence here, left by a mother’s betrayal and a solitary friend who’s moved away, barely filled by imaginary pen-pals, ghostly reminders of a love that was never there. Violence takes its place, leaving this eternal child beaten, with the vacant stare of the "nearly dead". He’s just like "a hundred little Johnnys, who went the same way". Is this Rechy’s Johnny Rio again? Stricken by an emotional howl as he cruises? Or Nik Cohn’s Johnny Angelo? The infantile, self-destructive rocker who possibly inspired Ziggy Stardust? A saxophone chugs and synths buzz in the ever-receding sweetness, ending with a desperate plea to all that’s left in this "limbo of loneliness": God. The trauma in ‘Little Rough Rhinestone’s darkling fairy tale was all too real. Almond’s troubled family background – his estranged father was talking to the tabloids at the time – was a woefully insufficient foundation for navigating fickle fame and homophobic abuse around every corner, from unfunny Rowan Atkinson skits to bullying from other musicians at London’s Columbia Hotel, according to Associates’ Alan Rankine.

‘Meet Murder, My Angel’ is, for Almond, "the darkest Soft Cell song of all – about the lover who wants to murder his love as the ultimate expression of affinity". It’s a ballad as malevolent as Robert Mitchum’s preacher Harry Powell in 1955’s southern gothic noir, Night Of The Hunter, hands tattooed with love and hate, resembling Sodom’s sleeve. Ball’s sound design is stunning: sombre but glinting synth pop, with feedback and ghostly twang, recalling Joe Meek’s gothic productions circa 1961, John Leyton’s ‘Johnny Remember Me’ and The Moontrekkers’ ‘Night Of The Vampires’. Almond hovers over the retro-futurist horror, multi-tracked like a horde of satanic Johnny Rays, their airy menace met by his climactic lower register’s real terror closing in after the diabolical lure of this sinister serenade, predictive of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds’ 1996 album, Murder Ballads.

‘The Best Way To Kill’ was literally ripped from tabloid pages, inspired, Almond says by a "feature which described different types of execution methods… and asked readers to decide which was their preferred way to kill people". For Almond, the lurid survey exposed the sadistic rot in Thatcher/Reagan’s "moral straitjacket", a malignant virus that bleeds into AIDS anxiety, where "dishonesty breeds like poison in an unhealed wound". But its also another punky "two fingers up" at aspirational pop’s confines, wanting to "tear it down, rip it up", reroute pop back to punk’s original, idealistic, revolutionary zeal. Sodom was, for Almond "a phlegm of gob spat in the face of whoever". From fear-inducing authoritarians to callous critics ("the men with the pens") there are plenty of targets here.

‘L’Esqualita’ takes its name from the New York drag bar, then situated on 8th avenue largely catering to Latino and Black gay men and transgender women. It’s a tale of a "Carmen in cling film" who will "take on the whole floor", sex workers who "spend the rent on a new dress" and a ferocious diva who will "sing of her sequins with tears and with traumas". Rogues rub shoulders with the defiantly glamorous: "hoods", "Johns", "a slob of a Corsican junkie" named Kowalski, a name no doubt plucked from Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire. This is Jaques Brel-style chanson transplanted into an American demi-monde, Almond’s real life observations transfigured by a raw, tragic poetry evocative of both Williams and the Mexican-American Rechy again, but this time his 1963 beat-adjacent, hustler travelogue City Of Night. Bohemian squalor is immortalised in the lines, "We could go out to dinner, but we’re always on drugs" also conjuring up the Warhol crowd. Soft Cell embodied the Velvets’ spirit more originally and faithfully in 1984 than any pale, sexless Jesus And Mary Chain Xerox approach. Like the diva of ‘L’Esqualita’, Almond "hams it up but means every word", theatrically wringing every last vestige of drama from this seven-minute showstopper, which is brooding and derisive one minute, yearning with "a deep love for love" the next. Ball’s haunting synth and Barnacle’s sax add to the deep red pathos, tawdry like a nightspot, burning like a sunset. Foreshadowing solo Almond, it placed him, in pop’s gayest year, in a romantic tradition of queer libertines, at odds with Frankie’s priapic bad boys, Bronski’s politically charged normality and Boy George’s camp coyness.

If ‘L’Esqualita’ showed how far Soft Cell had travelled since 1981, ‘Surrender (To A Stranger)’ flashed back to their synth pop origins. The central location a "one-night hotel", sex in rooms pungent with "tobacco and sweat", unwashed sheets with "stories to tell", disapproving looks dished out by the man on the desk. Attempts at escape veer from Almond’s incantatory flourishes soaring to far-off places, to sad daydreams about "being someone I could believe in", to death by frothy coffee ("drowning in my cappuccino"). Almond, alienated, caught between puritanical judgement and loveless grind, can’t distinguish Adam and Eve from Sodom and Gomorrah. Another torrid maelstrom, another "existential howl" into a spiritual void.

Throughout Sodom imagination fails to triumph over bitter reality just as Almond’s restless artistry couldn’t fend off a hostile world. Those tensions had always existed in his characters, the bedsitter torn between glitzy club-land and dingy lodgings, the ‘Facility Girls’ with "true love stories" romances and paranoia. They would resurface on ‘Soul Inside’ b-side ‘Her Imagination’, a Baby Jane-style saga about a woman trapped inside dashed dreams of movie stardom.

On ‘Where Was Your Heart When You Needed It Most?’, Sodom’s climactic apocalypse, there’s no exit from a "living hell" where people are reduced to sex-object commodities, where friends "die laughing" at your pain, even though "they cry the same tears". In this soulless dystopia the only chance of survival is to put on a mask, wear waterproof make-up, create a hard face with all vulnerability. The song is turned into a hellscape by Ball’s blast of noise, organ and walloping beats; disorienting, stentorian, hypnotic. All vestige of living grace is gone, save for a brief, wistful piano break, tenderness an illusion like "those photocopy soap opera stories". Almond’s taunting delivery and the titular question are a challenge to resist, defy and transcend at all costs, no doubt a note to self, its electrifying angst mirrored by The Cure’s Disintegration. It brought Sodom to a peculiar close, Almond and Ball reached dizzying new heights while their characters, romantic dreamers and fragile souls, sucked into this black hole horror, had nowhere left to go.

Peaking at 12, This Last Night In Sodom sat uneasily in the pop landscape of 1984, an uncompromising vision branded "commercial suicide". In Almond’s words, "it fizzled out", sinking into the shadows as Wham!, the tanned, grinning antithesis to Soft Cell, went imperial as summer’s charts heated up. By then Soft Cell were gone, disbanding after two sell-out nights at Hammersmith Palais, grief sweeping across tear-stained audiences, as a coked up Ball couldn’t feel his face. Earlier in January, he told Smash Hits "three albums is all we could ever manage". Almond echoed the sentiment in No.1 wanting to avoid "Soft Cell churning out album after album year in year out". But he was fraught with mixed emotions, painfully aware of what they were squandering.

This Last Night In Sodom may have found Soft Cell torn and frayed, "going down fighting". But chaos isn’t necessarily inconsistent for Soft Cell and the album hangs together more fluently than most 1984 UK pop albums. For all the year’s blockbuster brilliance, outside of cool jazz (Café Bleu, Diamond Life), Black America (The Poet II, Purple Rain) and indie (The Smiths, Rattlesnakes, Reckoning), most of 1984s treasures spun at 45 not 33 rpm. The grand 80s folly had truly arrived; Bowie’s Tonight, The Jacksons’ Victory, Culture Club’s Waking Up With The House On Fire and Frankie Goes To Hollywood’s record-breaker Welcome To The Pleasuredome. Beyond great singles, behind high-gloss production and beneath alluring sleeves, there was little else to these major releases. That May, The Human League’s long-awaited Hysteria had been a bland disappointment.

Post-split, Ball formed the short-lived Other People with wife Gini and Andy Astle. Almond returned in October with Vermin In Ermine and a clutch of string-enhanced Scott Walker-esque 45s, his wayward tendencies shrouding a survivor’s sturdy work ethic. For Ball, Sodom is "not technically perfect but raw, heartfelt and brutally honest". For Almond, it was "the definitive Soft Cell record". You could say the same of their preceding two, but where The Art Of Falling Apart is bolstered by its assorted single b-sides, This Last Night In Sodom, like Non-Stop Erotic Cabaret feels satisfyingly, devastatingly complete. In the next century Soft Cell would reform, but their original 1984 swan song remains one of pop’s grandest, grubbiest exits, expanding with possibilities as it soundtracks disintegration.