"O wad some Power the giftie gie us / To see oursels as ithers see us! / It wad frae mony a blunder free us / An’ foolish notion". These words, written by Robert Burns in the late 18th Century, are ever-green. What waster with a love of amplified racket gets to to see their own work at one step removed, as if through the eyes of others? Yet this is exactly what happened to Ministry’s Al Jourgensen recently when he was dragged by some well-meaning friends to see a tribute band to himself. Moreover, this was the band With Sympathy, named after and exclusively performing an album that for nearly 40 years he’d viewed as a foolish blunder. He came face-to-face with a very personal nemesis. "There was no advance warning, there was no guestlist, there was no VIP, I just showed up… wasted," Jourgensen said with characteristic candour on a recent YouTube interview. "I was amazed. I watched 800 people on a Tuesday night in Echo Park really responding to this and went like ‘Whoa, I don’t get it’. So the next day, I went back and listened to the album and I hated it as much as ever! It brought back a flood of different emotions. But by the end of it, seeing that band made me realise that this is not something to be angry about for the rest of your life. This is OK, let it go”.

The ill-starred With Sympathy, Ministry’s 1983 debut, can seem to be a confusing and even risible album for of those who know the band as sturm-und-drang industrial metal pioneers. The blistering triple whammy of albums from 1988’s The Land Of Rape And Honey via 1989’s The Mind Is A Terrible Thing To Taste to 1992’s Psalm 69 – The Way To Succeed And The Way To Suck Eggs essentially rendered void the musical avenues from which they came, marking out a scorched-earth pathway straight to some intimidating new aural Armageddon.

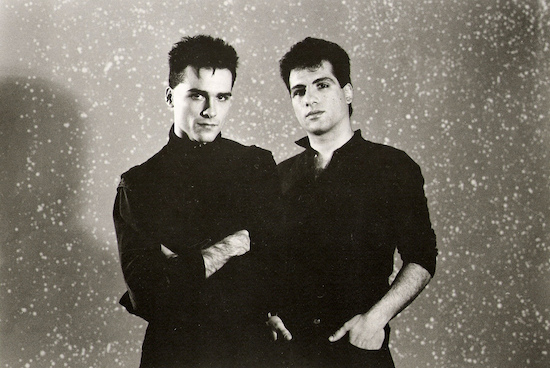

As a young fan who loved Ministry for this unholy triumvirate, stepping back in time via a copied C90 to the forbidden world of With Sympathy was an experience that provoked mirth and disbelief. It was impossible to square our spectral cult leader, he of the skeleton mic stand and Mad Max regalia, with this gauche synth pop meeting of Dave Gahan and Marc Almond. What was the story with Jourgensen’s peculiar faux-English accent – "Well I walked back, from this faraway land" he chirps on the Numan-ishly titled ‘Effigy (I’m Not An)’, "Walked right into a room with me mum and me dad".

We fans all knew that ‘Work For Love’ had been the ‘hit’ from this record but never saw it as a highlight, more a jaunty slice of upbeat and slightly unpalatable white-boy funk reminiscent of early Level 42. There was a track on here called ‘Say You’re Sorry’, for God’s sake. Could it be that Jourgensen, this supposedly fearsome iconoclast, had just been a bandwagon jumper all along?

In May 1983, when With Sympathy was released by major label Arista, it was stepping into a world in which the pop charts were evolving at an intimidating rate. Thriller, Michael Jackson’s world-conquering magnum opus of the previous year, was strafing the airwaves and the new horizons of MTV. ‘Beat It’ was the number one single in the US, with Eddie Van Halen’s apocryphally speaker-igniting solo marking a rare burst of raunch onto the mostly sanitised realm of US pop radio.

In the UK, the number one single was Spandau Ballet’s ‘True&#…