“I am not who I used to be. I came back haunted”

Nine Inch Nails

One evening in 2017, a 21-year-old musician called Haitao Yang was walking to his car in a parking lot. His life was about to change forever. He’d moved over to the US from Taiwan the year before for work. As he approached his vehicle, he saw two figures in the dark trying to steal it. “I just remember one person walking towards me,” Yang tells me. “Then I was on the ground.”

One of the carjackers had shot him in the head at close range. The bullet entered the side of his skull. What happened next has haunted Yang ever since. “There was a feeling of being so isolated and alone. I was floating in a giant ocean and there was no land anywhere. I felt impossibly isolated but at the same time it felt like I was really unsafe. It was viscerally terrifying.” Yang was having what’s known as a near-death experience. As we talk on Zoom seven years after the attack, with steel plates in his skull and years of extensive physical therapy under his belt, he’s still visibly shaken by what happened.

A near death experience (NDE) is an episode when a person sustains a severe, life-threatening trauma or injury – such as drowning, a heart attack, blunt impact, asphyxia – but survives. The unusual things they remember from these episodes have fascinated scientists and spiritualists alike for centuries, with some believing that it holds the key to understanding life after death.

Common characteristics reported by NDE survivors include recalling the sensation of floating above their own body and looking back at it, walking towards a light, a review of their life, meeting dead friends and relatives, a heavenly realm of peace and love, and often the opportunity to make a decision to either return to their human body or continue into this beautiful other world. Yang’s case was atypical however.

“It was very much a paradoxical feeling of everything being vast around me, but feeling claustrophobic,” he remembers. “It was nothingness, in a frightening way.”

After being revived, he spent days in and out of comas and that whole month is a blur to him. After leaving hospital care, he fell into an infernal depression. Months went by and he became aware that he had to find a way to process this traumatic experience. Just over a year after the attack, Yang had the idea to start a band. As a lifelong metalhead and multi-instrumentalist, he started writing music for a new atmospheric black metal project. Laang 冷, which means ‘cold’ in Mandarin, features Yang on vocals, guitar and production, with Willy “Krieg” Tai on bass.

“Some people keep a diary, I made an album,” Yang tells me, referring to their first record Hǎiyáng 海洋. “It’s helpful to be able to externalise what we feel,” he reckons. “This was my way of working through it.” Their new album, Riluo 日落,sees Yang reflecting on the “place beyond hell” and sharing “pieces of my experience I wasn’t comfortable sharing before, and mourns the loss of who I was and the acceptance of becoming who I am now.”

Yang isn’t the only person to be inspired to make music after having an NDE. Tony Kofi grew up in Nottingham and, upon leaving school at 16 in 1981, got an apprenticeship as a roofer. Whilst on a job one day he fell from a three-story building. As he plummeted, he was certain he was going to die and describes time “standing still”. He felt relaxed, and experienced a number of very specific visions. In them he saw places he’d never been, and people and children he’d never met. “The one thing that really stuck in my mind was me standing up and playing an instrument,” Kofi remembers in a BBC interview from 2021. “I just thought, ‘This is the weirdest feeling in my entire life.’ And then that was it, I completely blacked out.” Thankfully he doesn’t remember hitting the hard concrete headfirst. Days later, Kofi woke up surrounded by family in a hospital in Notts, bewildered and in serious pain. As he made his recovery over the coming months, this vision of himself playing an instrument – which he’d later find out was the saxophone – kept replaying in his mind. He claims he could even hear the music it produced. “Every time I closed my eyes, these images were there… I couldn’t understand it, I thought I was going crazy.”

He received compensation money and, despite having no interest in music before the accident, went straight out and bought himself a saxophone for £50. He believed that what he saw during his NDE was his future self, his fate, that he was “being shown something.”

Kofi taught himself sax by copying his parents’ old jazz records and trying to recapture the sounds he’d heard while in his altered state. He kept his visions secret but kept practicing night and day. His family didn’t support him at first but he was adamant. “I told my dad, if I go back [to not playing sax] I may as well have died in that fall,” he recalls. Eventually he applied and qualified for a scholarship at the prestigious Berklee College of Music in the US. After graduating he’s gone onto become an award-winning jazz multi-instrumentalist, releasing six albums and recording with artists such as Courtney Pine, Macy Gray and Harry Connick Jr. And now that he’s a father he’s sure that the children he saw in his visions were his actual children that he went onto have.

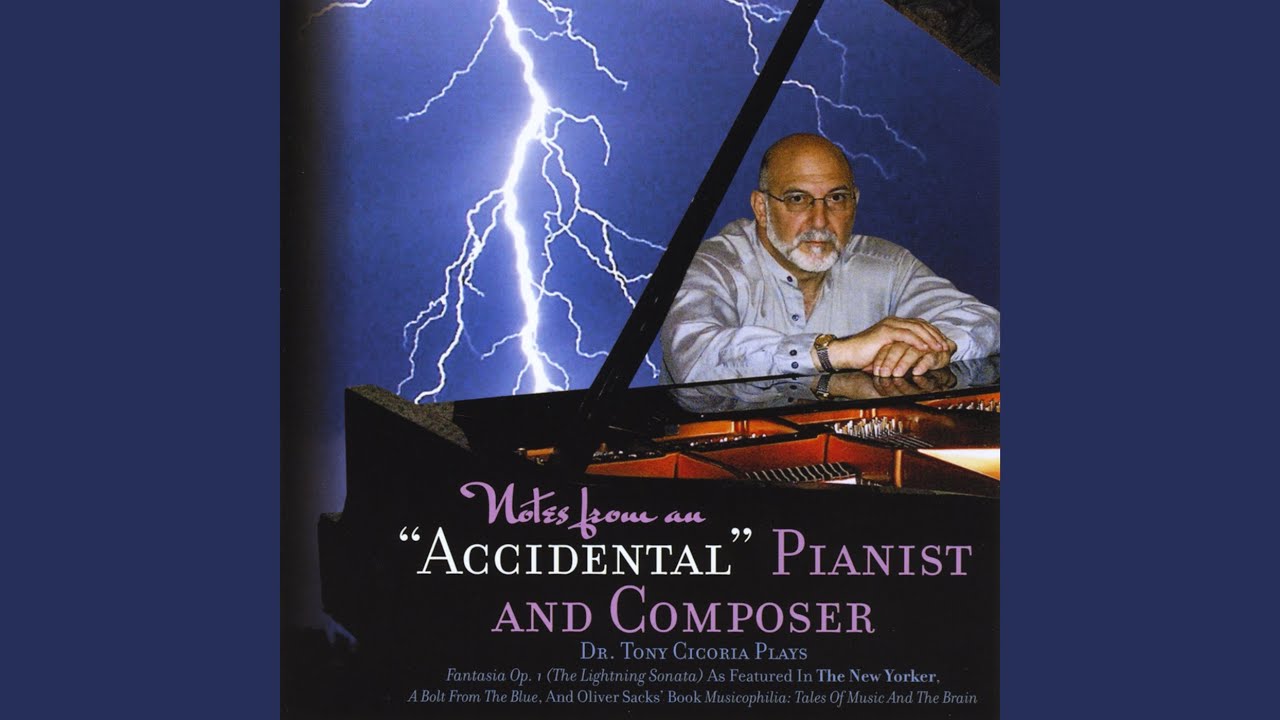

There’s also another Tony, orthopedic doctor Tony Cicoria, who in 1994 suffered a near fatal electric shock in a phone booth in upstate New York. “I was surrounded by a bluish-white light… an enormous feeling of well-being and peace,” he told the late neurologist, Oliver Sacks, in 2007. “The highest and lowest points of my life raced by me. Then, as I was saying to myself, ‘This is the most glorious feeling I have ever had’—slam! I was back.”

When the 42-year-old woke in the hospital he was delirious. “The fog cleared after a few weeks, and then I started to have this incredible desire to hear classical music,” he recalls, speaking to VICE in 2020. “So I bought this CD of Vladimir Ashkenazy, a famous Russian pianist, playing his favourite Chopin [pieces], and I started listening to it nonstop. But then I had this realisation that listening to this would not be enough. I would need to learn how to play it.”

Besides a failed attempt to learn piano when he was a child, Cicoria had previously had no desire to play. He wasn’t even interested in music, let alone classical, before the accident, but during his recovery he dreamed of playing his own compositions on the piano. “I would get up at four o’clock and I would practice until I needed to leave for work at six o’clock. I would then go to work and I would work 12 hours, come home, spend an hour with the kids – it was kind of my ritual – and then I would be back at the piano till midnight and I couldn’t see straight anymore.” In 2008, fourteen years after his accident, Cicoria stepped out onstage at the Goodrich Theatre in New York for his first public concert. He released his impressive piano concerto album Notes From Accidental Pianist And Composer the same year. It’s remarkable for someone who taught himself piano and had no musical ability until he was in his 40s. Reminds me of the old joke: “Doctor will I be able to play the piano after the operation?” “Yes.” “Great, I never could before!”

According to physician Darold Treffert, Cicoria developed a condition known as sudden savant syndrome. Treffert worked as an advisor on the 1988 film Rain Man and concludes a 2009 essay by describing his study into cases such as Cicoria’s as a way to “learn more about ourselves… and uncover the hidden potential – the little Rain Man – that resides, perhaps, within us all.”

Maz Sibanda is a septuagenarian psychic from Brighton & Hove‘s National Spiritualist Church. I spoke to her about NDE’s one morning over a coffee in a quiet café. “Sometimes it’s [the] spirit’s way of showing you what you’re capable of,” she explains. “We’ve all got our own guardian angels and our own guides that help us through life depending on what guidance we need.” Sibanda and the other members of the church claim that they communicate with the dead every week, something that helps those in mourning. “There’s a part of us that isn’t physical. That you don’t find in medical books. In [the] spirit you haven’t got pain, you’re just energy. I like being able to help somebody out of their grief when they come to church and give them evidence that whoever still lives on.”

Sibanda says that music is a big aspect of her relationship with the ‘spirit realm’. She realised this back in the 70s when she first began doing séances with her friends. “Spirit used to tap on the tables, they used to tap out songs, and we used to sing along with the songs. That was their way of building up energy. It turns out the guy under the table was my uncle, who used to play the drums when he was here.”

Spiritualists often sing together before séances, she explains. “Whenever you sit in a circle, you usually try to raise the vibration because you have to have some positive energy. How you do that is by talking and laughing and in some circles you sing hymns or music.” This connects with many spiritual and religious ceremonies from all over the world and throughout history, of course. In Buddhism, Christianity, Islam and Hinduism, for example, hymns, prayers or chants are often sung together to bring the group into harmony.

Obsessions with their NDEs is what led Cicoria and Kofi to become musicians, and Yang to start a band. But this type of experience can’t always be processed and transcended. Per Ohlin from the Norwegian black metal band Mayhem, who performed under the name Dead, was pathologically obsessed with his own mortality ever since suffering a particularly grim NDE as a schoolchild in Sweden. The victim of ruthless bullies growing up, vocalist Per once got beaten so badly when he was ten years old that his spleen burst. His mother found him unconscious without a pulse in his room days later and gave him CPR. It was touch and go and he ended up in a coma for some time before recovering, physically at least. This brush with death started a macabre obsession with his own mortality that led him to bury his clothes so they’d rot and “smell like a corpse”, to collect and inhale jars of decaying roadkill, self-harm to the extent that his arms needed to be fixed up with GafferTape, starve himself until he suffered near constant nosebleeds and even to sleep in coffins. After fronting the seminal band for three years he tragically took his own life, sparking off a chain of events that negatively altered the entire course of black metal.

Given the advances in modern medical science – with many who once would have died now being revived and resuscitated in hospital – it’s safe to assume that more people have NDEs now than ever before; around 40% of those who’ve had CPR or cardiac arrest, according to one study. But NDEs are by no means a new phenomenon and researchers are now reconsidering their significance through history. Traditional rites of passages are now being reinterpreted by some to potentially have involved NDEs. One such idea is that immersion baptisms (as thought to have been carried out by John the Baptist) were in fact ritualised drownings – a way of helping followers “see the light”, lose a fear of death and be “born again” – in other words, near death experiences. It’s clear that NDEs can often be life-changing for the survivors, so, the theory goes, St John could’ve been inducing such profound transformations amongst early Christians. So profound, in fact, that Jesus himself was awakened to his own holiness and his relationship with God through one of these very experiences at the hands of John The Baptist. The Gospel of Mark [1:10-11] reads, “As he was coming up out of the water, he saw the heavens torn apart, and the Spirit like a dove descending upon him. And a voice came out of the heavens, ‘You are my son, the Beloved, with you I am well pleased.’"

John Neihardt’s 1932 book Black Elk Speaks is the powerful story of a chief and holy man of the Native American Sioux who describes what some have interpreted as an NDE undergone while he was severely ill as a child. While lying unconscious for twelve days, “dying and just breathing barely” he remembers “Thunder Beings” coming from the clouds, flying horses and visiting the council of the “six Grandfathers”. He saw his experience as a revelatory spiritual message about the sacredness of earth and all which lives here.

In cinema, the concept was tackled in Joel Schumacher’s 1990 thriller Flatliners, with Julia Roberts, Keifer Sutherland and Kevin Bacon. The well-loved B-movie follows a group of medical students who experiment with journeying to the life/death threshold to see what will happen. By stopping their hearts and then restarting them, they explore an intense and kaleidoscopic other world. It’s fun at first but things soon turn dark as they’re visited by past traumas, regrets and mistakes. “Everything matters, everything we do matters,” Kiefer Sutherland’s character exclaims.

Now is probably about time we stop and ask, what is actually going on in NDE’s?

Dr Jane Aspell is a cognitive neuroscientist who works at Anglia Ruskin University in Cambridge. Her research, she explains, includes inducing “something a bit like an out-of-body experience in healthy people using virtual reality… I do this because the broad topic of my research is how the brain creates a sense of self. In an out of body experience your sense of self is radically altered.”

She’s currently looking into this as treatment for chronic pain. “If you see yourself from the outside, we find that this can actually reduce pain in the person who has pain all the time. We’re not exactly sure why this happens but they talk about seeing themselves from the outside and it’s almost like they can they kind of feel compassion for themselves.”

I ask her, as a neuroscientist, what she believes is happening when people have NDEs. “I don’t believe that the mind and consciousness can exist apart from the brain. Being a scientist it doesn’t make sense with what we know about the world. Your brain can continue to be active even for a few minutes when the heart is stopped, especially if you’re in hospital and they’re doing CPR and things like that. So the brain doesn’t immediately switch off. It’s still alive.”

But where do the heavenly visions come from? “Your brain’s not getting enough oxygen and therefore it’s going a bit haywire. It’s creating these experiences for you, which includes the out-of-body experience. Our brain is able to create experiences that feel very real, but are basically hallucinations. Like when we dream.”

She cites the fact that people from all over the world have “similar brains” as the answer to why there are so many similar characteristics in different NDEs. She goes onto to say that the idyllic experiences are down to the culture and ideas of heaven and death that the survivors grew up around, whether they believe in an afterlife or not.

Dr Jeffrey Long is an oncologist who for the last 25 years has dedicated his life outside of his practice to studying NDE’s. He founded the Near Death Experience Research Foundation (NDERF) which has collected and studied over 5,000 experiences from all over the world – the world’s largest of resource of its kind. He’s also written two books on the subject, including New York Times bestseller Evidence Of The Afterlife: The Science Of Near-Death Experiences.

“In some of the more detailed experiences people hear a choir singing, instrumental music, some combination of things or something that really defies earthly words”, Dr Long explains, from his office in Kentucky, US. “They often feel a great sense of peace and love, and the music seems to be part of that big picture of enveloping love on the other side.”

Amongst the 5,000+ experiences detailed on the NDERF, is a description from a woman named Edna, who had an NDE while suffering pre-eclampsia during childbirth. “I was surrounded by the most wonderful music – similar to panpipes. This music was everywhere and the feeling was so peaceful and pain-free.” She recalls being told that she was in "The Halls of Music" – a “clearly mystical or unearthly realm”. Another NDE survivor, called Timothy N, describes hearing the sound of “thousands of bright voices singing in harmony”. He almost died while drowning as a child back in 1960. “The music I heard has made me very fond of music – I have even been a reviewer of ambient music for a magazine.”

Dr Long acknowledges the possibility that some cases on his site could be fake, and has come across a handful that seem to be. Overall, though, he’s confident that the thoroughness of the in-depth 50 question questionnaire puts the majority of jokers off, and the continuity in the results he reads suggests that people are truthfully sharing their experiences.

He sees the music that people make after having NDEs as “their loving outreach to humanity. They want to share something that was so inspiring to them, so incredible to them. People try to bring back a small piece of the heaven that they encountered to share with people around the world. It’s really an act of compassion to try to share that wonder with the rest of us.”

According to Dr Aspell, however, the link with NDEs and music, and our deep connection to music in general, comes from the fact that music and language activate similar brain regions. “When you’re listening to a person talking and you can hear the emotion in their voice. It’s because of the prosody and rhythm, it’s not the words that they say. So I think that’s what’s happening with music." This explains why music is a useful tool in conveying emotional information that words sometimes can’t, and why some use it to communicate the strangeness of the near death experience.

But what about the bleakly terrifying NDEs, like Yang’s? “First of all, they’re rare,” Dr Long explains. “In my experience of doing this for over 25 years, the great, great majority of people who believe they’ve had a hellish near-death experience actually didn’t. Something called ICU delirium is by far the most common event that’s confused with what seems like a frightening, hellish NDE.”

Laang

I ask Maz about Yang’s experience of a “place beyond hell”. “It’s very, very unusual, but sometimes people are stuck. They are too frightened to pass over. They might have regrets. They might think they’re going to get punished, because that is ingrained into you through religions. Especially through Catholicism, you think you’ve got to be good and God is watching you.” She goes onto say that in the Spiritualist Church they don’t believe in a heaven or hell, like other religions do.

So, what does all this mean for our understanding of the afterlife?

Neuroscientist Dr Aspell believes that “It’s just the way our brain responds when it’s deprived of oxygen”, she tells me. “This is not to say that there is no afterlife. I hope there is. But I don’t think that the near-death experience is necessarily good evidence for it. I think the explanation is the fact that we have similar brains which respond in similar ways.”

Kofi and Cicoria, like many NDE survivors, believe that there is an afterlife waiting for us and that they’ve been there. Dr Long concurs and sees his research over the last 25 years as evidence. Yang, however, is not so sure. Reflecting on his harrowing NDE he says, “If there is an afterlife, I hope it’s not that. I never want to experience that again.”

What is clear, however, is that studying or experiencing the mysteries of what happens when we die often serves to reinforce the sanctity of our time alive. What actually happens when we die is yet to be fully understood, but just as music is a big part of our lives, it too may be big part of what happens after.