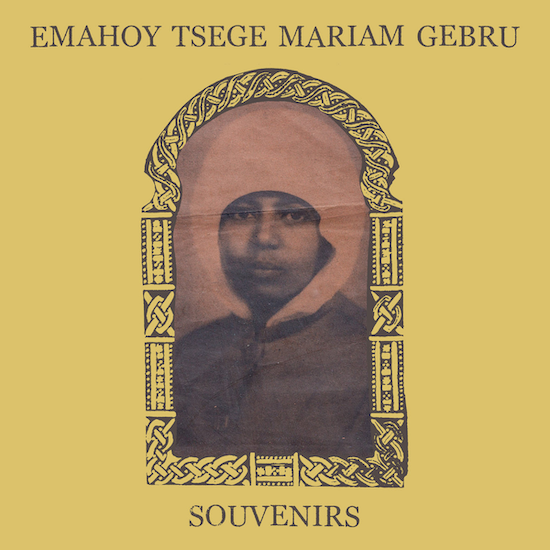

It is easy to forget how fundamental the idea of home is and the emotions that this idea can evoke in times of distress. “Clouds moving on the sky / My heart has never stopped missing home”. We can hear the voice of Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru singing these words on the opening track of Souvenirs, a selection of home recordings she made while still home in Addis Ababa during the 70s and 80s, but reflecting on a dangerous period of exile which was bound to come. Later, she wonders, “Crow of the sky / …Let me ask, have you returned / from my beloved country?” The feeling of longing is immense. Her work exists on a threshold between ‘running away’ and ‘aiming towards’. It’s hard not to connect her separation from home with images of Ukrainians emigrating from where they were born or Palestinians looking for sanctuary slightly closer to – but still absent from – home. There is no room for souvenirs when grabbing a small rucksack or carry-on bag in a rush. Emahoy made the souvenirs of this album by herself: they are compositions created in a most simple fashion by pressing record on a cassette player, into which she sings and accompanies herself on the piano.

This compilation album, released today by Mississippi, is a collection of songs of loss, mourning, and exile. Recorded between 1977 and 1985, these compositions differ from anything previously released by the artist. You can hear the birds outside the window as Emahoy performs; it is intimate, you feel as if you are sitting beside her. Written and recorded while still living at her family’s home in Addis Ababa, she sings not just generally with nostalgie but also specifically reflects on the 1974 revolution in Ethiopia, sparked after several years of drought and an outdated socio-economic structure, which was followed by the Derg military coup and the Red Terror in Ethiopia.

Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru’s name is a result of her life as a nun: “Emahoy” is a title given to female monastics in the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church (like “Sister” or “Mother” in other Christian traditions), ‘Tsege-Mariam’ is a chosen name (meaning “flower” and “Mary”), and ‘Gebru’ is the name of her father. She was born in 1923 in Addis Ababa into a family of intellectuals privileged in the country as far back as the 12th century. This certainly influenced her opportunities in life: at the age of six she went, with her sister to learn piano and violin in Switzerland, the first Ethiopian schoolgirls to do so. There, her talent was nurtured and she was also exposed to Western classical music. At the age of ten, she returned to her homeland and played regularly for Haile Selassie. Her relatively elevated position in society opened doors for her that were not generally opened: she was the first woman to work in the Ethiopian civil service, to sing in an Ethiopian Orthodox church and to officially translate.

This state of affairs lasted only a short time – in 1936, Mussolini’s forces invaded Ethiopia. Some members of her family were killed, and the rest, along with Emahoy, were deported to Asinara Island and then on to a tiny village close to Naples. After five years of occupation, she resumed her studies in Cairo under a Polish violinist, Alexander Kontorowicz. She learned the music of Schubert, Mozart, Chopin, Strauss, and Beethoven. But life in North Africa did not suit her and she returned to Addis to work at the Ministry of Foreign Affairs – this time as the country’s first female secretary.

Her ‘sliding-doors’ moment might have happened when she was 21, but Selassie refused her permission to go to London, even though she had been offered a scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music. She fell into despair and nearly paid for it with her life. She turned, instead, to religion and abandoned music, became a nun, and spent ten years in a hilltop convent in Ethiopia – her new ascetic routine including always walking barefoot. A decade later, the death of the religious community’s leader became one of the reasons why the group began to fracture, so at 30, she returned, yet again, to Addis.

Emahoy started playing music for the third time. But this time she eschewed the Western canon – instead of Chopin’s mazurkas and Beethoven’s sonatas, she created original compositions. Influenced by the experiences of the previous decade, she wrote pieces such as ‘The Homeless Wanderer,’ ‘Mother’s Love’, and ‘Homesickness,’ infusing the classical training of her youth with the pentatonic chants she was singing in church. This time, the emperor permitted her to travel abroad, so she went to Germany in the early 1960s and recorded her first music, released on Spielt Eigene Kompositionen in 1967. For the next decade, she turned increasingly towards Western classical models, using titles including the words “nocturne”, “sonata” or “symphony”, with a clearly emphasised exposition of the compositions and their developments. She was opening up to the world, but the world was not yet aware of her – the question of whether this was her strong intention, or to what extent it was necessary for her name to become established in the West, of course, being another matter entirely.

Either way, it was another two decades before broader interest materialised in her work. Since the late 1990s, the French musicologist and producer Francis Falceto has been releasing albums of Ethiopian music from the 50s, 60s and 70s via a series called ‘Éthiopiques’ on the Buda Musique label. Thanks primarily to this venture people across the world now recognise the different sonic characteristics of Ethiopian musicians such as Mulatu Astatke, Mahmoud Ahmed, Gétatchèw Mèkurya and Muluken Melesse. But number 21 in the series was a record that existed as far away as possible as it felt possible to get from Ethiojazz while still being recognisably from that country. And it featured the music of Emahoy Tsege Mariam Gebru.

If Astatke and Mekuryia turned Ethiopian musical traditions towards jazz, she carried out a similar manoeuvre with classical music. Her compositions have a remarkable fluidity and are full of virtuosic ornamentation, but it is a riddle to assign them to a particular genre and tradition. There is the serenity of Eric Satie in the pentatonic scales, and the delicacy of Debussy. And if one finds something of jazz in them, it is more likely to be in the complex music of Duke Ellington or Mary Lou Williams.

An incredible part of the increased interest in Emahoy’s music was made thanks to Mississippi Records, which released her first official vinyl record a decade ago – a compilation of recordings from the 1970s. Kate Molleston created a documentary, The Honky Tonk Nun and included her in the Sound Within Sound book. Mississippi Records then followed up on interest in Emahoy’s music with the exceptional Jerusalem album a year ago. It highlighted that fact that the Nun had received conventional music training which was far more European than Ethiopian in its precepts.

Souvenirs was originally sold by the artist herself as a homemade CDr and as such was known to relatively few. But this album actually opens another chapter in her career: this time she sings. These moving anthems were recorded as a personal statement, intended to be private due to censorship, probably without the intention they would ever be released generally. But finally, they are here with us because of the many coincidences in the musician’s life.

What is also different from previous recordings released by Mississippi is the sound quality, which up until now has always been clear and clean. Souvenirs has a low-fidelity quality which makes it an analog of bedroom pop. But the extraneous noise and murk doesn’t matter, as the emotional charge in these exceptional pieces is incredible, suffused with some of the intensity of the times they were recorded in. A decade after these recordings were made and her mother died in 1984, Emahoy joined hundreds of thousands of other Ethiopians in exile, bringing these tapes with her. At the age of 50, after experiencing war, exile, study in Europe and Egypt, a decade in a monastery, and the release of three solo piano and organ albums, she went into poverty, joining the Church of Kidane Mehret in Jerusalem. She remained there for the rest of her life. Until 2005, she had no access to a piano, so she composed only on paper. Until 2014, her music was typically hard to come by.

This has changed thanks to pianist and improviser Maya Dunietz and her husband Ilan Volkov (principal guest conductor of the BBC Scottish Symphony Orchestra), who published her compositions in a printed volume for the first time. They were supposed to meet the composer last year, but sadly she passed away in March. But she left archive recordings in her cell, including three boxes of cassettes, among them the original version of Souvenirs.

What we can hear now comes from a deep commitment. Despite restraint and other difficulties, her main focus on her spiritual practice later in life which meant she barely played and lived in obscurity. Souvenirs is another piece of this puzzle, a document of exile and war made by a virtuoso, mesmerising pianist in supposed privacy. It still resonates with the beauty with which it was imbued but has also gained a more modern, universal patina.