May the angels bright

Watch you tonight

And keep you while you sleep

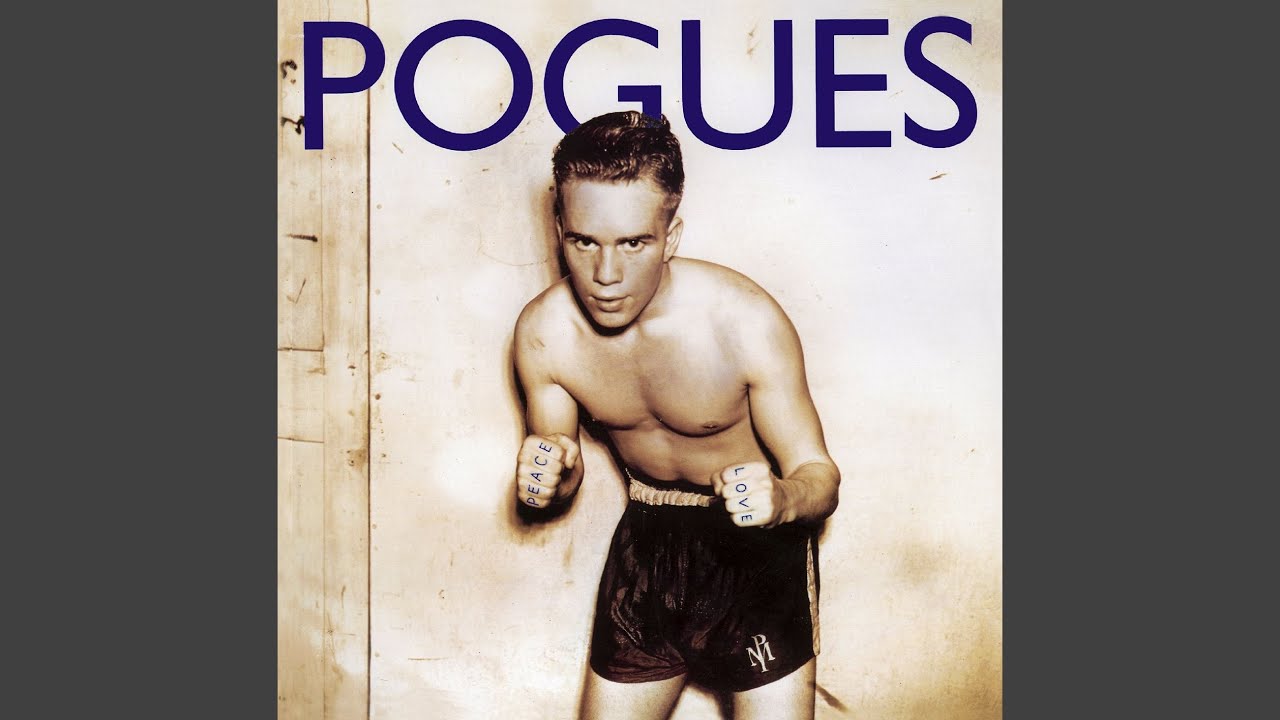

The Pogues – ‘Lullaby Of London’

This is only the second time in my life that I have written anything while fitfully crying. The first was the funeral address for my father. While we know that death is coming to us all, there are some deaths we particularly dread because we know they really will occur. I do not wish to minimise the importance of Shane’s (and I’ve never heard anyone who loved him ever refer to him as just “MacGowan”) dying to anyone else, but in my case I lose a link that helped bring who I grew up to be into the world, a soul who helped me recognise that I had one, and a man whose perceptions and sensibility were like spirit guides for a boy yearning to connect with a greater and richer reality than homework, the rules, and 1980s television. Shane oversaw my path from wanting to be a cowboy (a calling he may actually have had sympathy with, given his appearance in and on the soundtrack of Alex Cox’s Western Straight To Hell, and The Pogues identification with outlaws), to becoming a writer. The very notion of a role model is so trite as to call ahead for ridicule, I know, yet extraordinarily for a man who spent the last eight years practically immobile, who had not released a new song since 1997, and who as early as 1990 was saying that another drink would kill him, I grew up wanting to be like Shane MacGowan.

There is very little point in trying to get away from the centrality of alcohol in any appreciation of Shane, and in his relationship with himself. I’ve often found that the appeal of The Pogues in general, and Shane in particular, is lost on people who find nothing innately cheering in carousing or revelry, and who distrust the excitement of raw, unguarded, open and noisy human communion. Undoubtedly the raising of the collective temperature and mass shedding of inhibitions that occur when people and drink meet were a big part of what made The Pogues and the people who loved them tick. The warmth I felt when I first heard Shane’s voice was very like that first experience of drinking too much, without recognising that I was drunk or what drunkenness was, an induction into a near religious sensibility that changes the mood before eventually altering all of reality. Hearing his voice reached and opened my heart, enabling it to function as part of an aesthetic response to music. And that in turn introduced me to the faculty of feeling itself, not in the childish form of what had passed for emotion before, but the full blooded adult kind that forced me to grow up and find out what was inside me.

Shane’s voice, even more than his lyrics, was the ultimate instrument of light and darkness. Part of this came from his punk background as he could jeer and snarl with the ugliest of them, but he could also display the tenderness that only someone with real strength of character – very different from simple strength – can. On songs like ‘The Sick Bed Of Cuchulainn’ and ‘Bottle Of Smoke’, Shane sang with the irresponsibility and recklessness of one flinging his life against a wall like a glass, smashing himself to pieces in case last orders were called early. At the same time, his vocal on ‘The Parting Glass’, sung when he was still in his mid-twenties, shows that his violent exuberance and rumbustious volleying about was no thoughtless pose. Here he knew the value of life, of what he was casting aside to momentarily experience more, and remained utterly unrepentant as he did so. His factuality was frightening and was meant to be so. On odes to all day drinking like ‘Streams Of Whiskey’ and ‘Boat Train’, songs carried by the giddy jouissance of the moment, the issue of there being a downside is not only acknowledged but accepted with dispassionate sanguinity. On ‘The Sunnyside Of The Street’, he flatly declares: “I will not be reconstructed.”

The painful consequences of not giving a fuck are even more evident in his songs of reflection (‘Lullaby Of London’, ‘Five Green Queens And Jean’), which are sung entirely without self pity, delivered with an imperious shuffle and swaggering nobility, born of the conviction that “the dark end of a lonely street” is where existence loses its pain. In never feeling sorry for himself, there is a suggestion that Shane is never really sorry for anything, which alludes to an even greater darkness in his oeuvre, and in the life of any serious drinker, as what is seeing through all things but a small step towards caring about nothing at all?

Many of the great singer songwriters were born with old souls (Dylan, Reed, Cohen), and Shane was no exception. The irony in his case is that while in his youth he sang with the authority and wisdom of an older man, by the end of his recording life, though still only in his thirties, Shane just sounded elderly. Though lovely and forlorn, his voice on ‘Lonesome Highway’, where he is captured slumped in a bar wearing a Pittsburgh Penguins ice hockey top, singing with his eyes clenched closed as if there is no other way he can squeeze the words out, has to be the weariest vocal ever committed to record.

The discomforting upshot is that for someone of Shane’s gifts, the kind bequeathed to genius, seven albums (five with The Pogues and two with The Popes, as well as a live compilation with The Nips) is not only less than fans would hope for, but far less than many of the all time greats he venerated (Young and Morrison) and also the two contemporaries (also possessed by genius) whom he was frequently lumped in with, Mark E. Smith and Nick Cave. Up until the early nineties Shane enjoyed rough productive parity with these peers, before falling away. While Smith, who despite being persistently out of his box was a prolific album-a-year man to the very end, and Cave, who carefully understood and took his talent as far as it can go with a career of multiple renaissances, ploughed on, Shane hit a wall.

That Shane entered 26 years of creative silence, if one discounts his simply being too incapacitated to pull it together to record new material (which I do, he was no hermit and never “retired”), can seem inexplicable. Unless, that is, one considers the nature of his gift as something elemental. Once it had run away that was it, it was not coming back. His inspiration must, I think, have been so natural that he had to force it to become art, as it would otherwise have remained simply character and charisma, and been subsumed in life. In all probability Shane had relatively little control over his muse, far less any disciplined way to access it (he spoke of simply waking up and writing his masterpiece ‘Rainy Night In Soho’, having passed out the night before on a combination of whisky and acid), especially as he grew gradually less bewitched with the world. Even at his peak and prime, footage of Shane, onstage and in public, often shows a man who has trouble keeping his head up; this of course could be shyness or alcohol, but I think it was evidence of someone who was in turns enchanted by his gift and daunted by its weight.

For a while tradition acted as a support and home for Shane. He came from the school of the Celtic bards and hellraisers (as his definitive interpretation of ‘The Limerick Rake’ is testament to). This is a tendency that has fallen somewhat out of fashion, perhaps tasting too much like toxic masculinity for some appetites, encompassing actors like O’Toole and Harris, writers like Behan, and of course, musicians as broad as Thin Lizzy and The Dubliners, and before them, the mythology of Ireland (and of Britain, with The Pogues hailing from and influenced by both). Even by the standards of this freewheeling trajectory though, Shane was an unconventional fit, his musicianship sired by singing on the kitchen table as a child and humming the tunes he wanted his band to play. To that end, The Pogues’ contribution to interpreting and supporting his great visions ought never to be overlooked. Shane rightly enjoyed a reputation as an inspired lyricist, ‘London You’re A Lady’ is one of the few lyrics in rock that can credibly claim to be a poem set to music, yet some of his most affecting vocals were on songs written by band members: the anthemic ‘Thousands Are Sailing’ by Phil Chevron; the country rock classic ‘Bastard Landlord’ and the majestic ‘Misty Morning, Albert Bridge’, by Jem Finer. It suggests that he knew, despite occasional public carping, what he owed them. The flip side is that though The Pogues released two albums without Shane, there isn’t a song on either that would not have been lifted by his voice. It is hard not to speculate that having outgrown his group, and possibly also his tradition, having being completely immersed in both, robbed Shane of the openings that allow an artist to keep developing and moving forward, and that he floundered to find a new voice.

Conversely, his silence might also be explained by his having succeeded in what he set out to do so early on, as a poet of place. This strikes me every time I walk anywhere that has featured in a song of his. I am tone deaf and always get lyrics wrong if I try and sing aloud, but walking on my own I render word perfect renditions of lyrics of his I have been listening to for 36 years, because the places help me get the words right. This is musical tattooing, Shane’s words committed to my gut like hymns or mottoes, verified by the environment he was describing. Just two days ago I walked along Piccadilly and heard ‘The Old Main Drag’, as I always do, a lyric delivered with matter of fact simplicity, awash with compassion without sentimentality. Shane respects his subject too much to strive, and never plays on the listener’s emotions by exaggerating or emoting because he does not have to; the song is all there on Piccadilly. As such it stands as a refutation of the kind of insult that will emerge again after the initial tributes are done, the snide and racist insinuation that The Pogues were a Plastic Paddy ‘top of the morning’ show-band, fronted by an embarrassing drunk that ought never to have been allowed out of a Kilburn lock in. Sadly it is the sort of thing you hear too many times if the answer to ‘Who’s your favourite songwriter?’ is Shane MacGowan.

Tellingly though, in the last few hours I’ve heard from people who have been hit harder than they thought by the news of Shane’s death, and who in some cases are struggling to work out why. I think it is because Shane understood something precious about life that he helped us understand too, simply by virtue of being himself. We love people like that, and miss them differently from those we simply admire or appreciate. Shane MacGowan is an emotion, a feeling that will persist in his absence for as long as we are romantic and realistic enough to insist that songs, his songs, are the rational response to the confusion and joy of being as free with ourselves and feeling, as he was. May we all aspire to leave as much to those who look up to us.