The sound of a zither or a psaltery or a dulcimer – a wooden-bodied, finger-plucked or hand-hammered, fretless instrument, often held in the lap or manipulated near to the body – can provoke a bracing, often spiritual sensation in the listener. Where does that come from? Is it because of powerful albums like Laraaji’s Ambient 3: Day Of Radiance, PJ Harvey’s White Chalk or Jean Ritchie’s Appalachian Dulcimer? Is it about the survival of these old, fragile instruments in an increasingly digital world? Or is it about the contact of a fingernail or soft skin with thin metal or gut, and the noise this startling connection produces, a sound that ultimately vibrates in a body held tightly and tenderly by the performer to his or her own, or is manipulated carefully by touch?

For me, it’s all three. A resonant, historical imagination always trembles in recordings of these distinctive, usually handmade instruments, and on Dorothy Carter’s Waillee Waillee, oceans of feeling oscillate, undulate and reverberate after only a few bars of track one. This is partly about the way Carter’s instrument is played – she creates patterns of repetitive shiver rather than shimmer, at the ends of phrases or through whole melodies, often on top of heavy drones played on bowed chimes and steel cellos – but also because the initial sonic hit has a tough edge, cutting and slicing through the surrounding silence like a knife, before shaking all over.

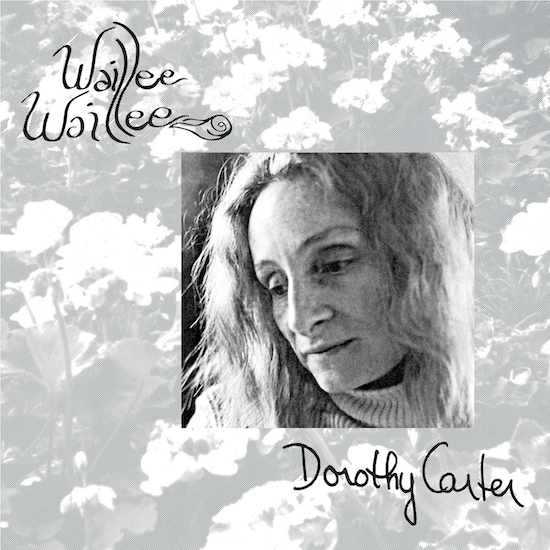

Originally released on a private press recording in 1978, and now reissued forty-five years later by New York experimental label Palto Flats and Putojefe Records, Waillee Waillee was made by Carter when she was 43, a single mother with two young children: a son, Justin, and a daughter Celeste, after whom she named her label, hinting towards her love of unusual instruments (a celeste is a high-pitched bell-piano and the chiming instrument that leads Tchaikovsky’s ‘Dance Of The Sugar Plum Fairy’).

Parts of her early biography appear conjured up by folksy, hippified AI. Born in New York City in 1935, she lived in a commune, worked on a Mississippi steamboat as a ship’s boy and ran away to a Mexican cloister with an anarchist priest (haven’t we all). On the liner notes, Danielle de Picciotto [of Hackedepicciotto], a good friend of Carter’s when she moved to Berlin during the 1990s, says she grew up in her grandparents’ Victorian mansion in Boston, living a lonely childhood, hidden away in the huge library playing piano, “listening to her grandmother belching”. She was also “not averse” to psychedelic experimentation or herbal science.

But beyond the mythology-worthy, Lemony Snicket-like background, Carter was also someone who studied and played doggedly, working hard to promote the traditional tunes and techniques that she loved. Initially a performer on the Irish harp studying music in conservatories in Paris and London, she devoured books on music of the Renaissance, Elizabethan courts and the French troubadours. Shown a psaltery in a music repair shop while getting her harp fixed in the 1960s, she “found a strange recognition… THIS was the instrument I wanted to play”. (Carter was putting together notes on the history of the zither family before her death, excerpts of which are printed in the reissue liner notes.) The fact these instruments were accessible to people without musical training and were “easy and quick to learn," also inspired her.

Carter also co-founded an avant-garde New York music and art gallery and a new age collective, Central Maine Power Music Company (CMPMC) with Constance Demby and Robert Rutman, touring music and art in museums, planetariums, colleges and universities. (Rutman also invented the steel cello and bow chime, what he called American industrial folk instruments, the playing of which gives Waillee Waillee an extra-terrifying layer of atmosphere; he also released Waillee Waillee on cassette on his label, Rutdog Records, following the Celeste vinyl version and the masters were found in his Berlin studio after he died in 2019.)

In Carter’s last decade (she died of a stroke, living in New Orleans, in 2003), she briefly found fame as a co-founder of the Medieval Babes, whose first album, Salva Nos, was an international hit, before she parted ways with the band. Her tours of folk festivals in the mid-1970s, however, she writes in her notes, is where she “really started to learn about American folk music and traditional music.”

It’s instructive that her mentors back then included traditional lodestars like Jean Ritchie and Pete Seeger, but her liner notes feature tributes from experimental pioneers like Alexander Hacke and Laraaji. But listen to this astonishing record – made after a less avant-garde debut, 1976’s Troubadour – and those extremes make sense. Carter used her instruments to explore folk’s vibrating connections in radical, almost insurrectionary ways.

Its title, Waillee Waillee, refers to ‘Waly Waly’ (Wail, Wail), a folk song of Scottish origin, which has many iterations (as folk songs invariably do). Even though she may have learned it from friends, her lyrics and melody lines are close to Burl Ives’ 1952 version as well as Marianne Faithfull’s gorgeous cover in 1965, both of them under one of the song’s alternative titles, ‘Cockleshells’. Carter’s arrangement is starkly different, its metre shifting between eight, then five, then seven beats to the bar, pushing and pulling the listener into its tale of love being bonny and new, then fading and "waxeth cold". Its musical setting is also different to the other tracks, featuring Carter on piano, and Rick Nelson (not the rockabilly singer) on bass. Her playing has a 1970s Paul Simon singer-songwriter saunter to it, as if this is her attempt to be her most mainstream, the stop-start metre and a piercing recorder introduction aside.

Most representative of the album are the seventy-five seconds of doomy, tremulous hammered dulcimer that begin it, adding a sinister edge to the start of an American folksong, ‘The Squirrel Is A Funny Thing’. You wonder if Joanna Newson had a copy before making The Milk-Eyed Mender; its combination of naive, childlike wonder, minor-key witchy dread and manic playing certainly suggests the early 2000s US psych-folk class might have been influenced by an old copy. Carter’s singing voice, deep and keening, is also arresting. When she sings, “the rabbit’s got nothing for a tail, but a little bunch of hair” you wonder, with a chill, what she’s planning to do with it.

‘Dulcimer Medley’ follows, joining a 13th-century French troubadour tune, ‘Robin M’Aime’, and an Austrian dance. The effect of this mix of nursery rhyme melody and slightly out-of-tune twinkling is unexpectedly touching, creating a soundworld that burrows back to impressions of childhood, and the wound-up, wonky iridescent sounds of music boxes. The knowledge that these tunes have survived because of their simplicity is touching too, knowing they hang so delicately on these strings, and these instruments of real fragility.

Then comes a huge shift and one of the album’s most jaw-dropping tracks, ‘Along The River’. Taking lyrics from James Joyce’s 1907 collection Chamber Music (as have other artists like Jim O’Rourke and Steve Shelley), Carter creates an indelible, intense impressionistic epic, flooding the track with rich textures, painting a strangely tangible world. Dulcimer and psaltery strings suggest trickling water, falling water, heat haze. Recorders swoop softly above the mix like birdsong; Carter’s voice, high, woozy and feral, joins two minutes and twenty seconds in, telling us that love has “dark leaves on his hair.” Later, he bends his ear to music, Carter’s vocals swooping and diving like a swimmer in high heat, telling of us his “fingers gently playing upon an instrument.”

‘Summer Rhapsody’ is similarly abstract and ambitious, but more of a suite. An uncredited wind instrument — another recorder, or a kind of tin whistle – gives it a sinister air, like John Francis Flynn’s 2021 version of ‘Tralee Gaol’, before a bowed chime and shaken percussion suggest ozone-fried heat and sneaky snakes in the reeds (from the first minute to the second of this track, you imagine this drone soundtracking a particularly terrifying future-shock sequence of Koyaanisqatsi). The hammered dulcimer’s harsh textures keep pounding and pulsing, and you wonder for Carter’s wrists and fingers. There is an insistent, unstoppable fervour to this music quite unlike anything else I’ve – genuinely – ever heard.

‘Celtic Medley’ has a sweet, Christmassy feel, its notes ringing out like bells (it mixes Irish waltz ‘Planxty Irwin’, Scottish border ballad, ‘The Lonely Glens Of Yarrow’ and ‘South Winds’, an 18th-century Irish tune played by many American mountain dulcimer players). ‘Autumn Song’ is another Carter original, jittering, quaking, convulsing, log drum percussion joining her unstoppable rhythms. If this tune was a drug it’d be banned pretty quickly. ‘Tree Of Life’ begins like an outtake from Wendy Carlos’ soundtrack for The Shining, before building into a spectral, heavenly, fever dream. Then Carter’s wordless vocals come in, followed by reverberating, echoing ruminations on the cycles of nature, her syllables stretching over many seconds, forcing us to listen in, listen deeply, in a way that recalls the deep work of Pauline Oliveros and the recent, gorgeous album Tree by The Durutti Column’s John Metcalfe.

“The tree of life/ Growing everlasting branches”, Carter sings, slowly, wailingly, purposefully, beautifully – but it is when her vocals echo her instrument’s melodies directly on this track that this album reaches its peak. There is so much to revel in, to be stunned and staggered by in this astonishing record, but when her sound is indistinguishable from the sound of her instrument, when her vocal chords and her hammering hand become one, tightly and tenderly, the bracing, spiritual sensation is enough to make me believe in anything. The power of music to soar us spiritually skywards forever, for all time, for starters.

Waillee Waillee is reissued on 1 December by Palto Flats and Putojefe Records