Tom Waits, New York, 1985, Anton Corbijn

One of the more revealing cliches of fantastical fiction is the rubbish dump world. It’s a cliché within a cliché – the mono-habitat single biome planet – and though there’s little logic why such dumping grounds would come to exist, their usefulness is clear for storytellers. They provide layered environments, full of anachronistic tech and retrofitting opportunities, accidents and innovations, suggestions of an ancient future, as well as plentiful underdogs and overlords. In a deeper sense, the attraction to rubbish dump worlds may lie with one decisive factor – they are not fiction. This is physically true, given how the West uses the so-called developing world, from electronic waste dumps in Ghana to the shipbreaking ports of India and Pakistan. It is also culturally true. Our prevailing view of the past, seeing distant pinnacles from our own lofty position, is the result of historical astigmatism. An alternative sharper view is that it’s all junk, colossal piles of it from earlier epochs and our own, through which we constantly sift and recycle for our daily needs. We don’t have to imagine the rubbish dump world. We already live in it.

In one of his periodic, frequently hilarious, appearances on the Late Show With David Letterman, Tom Waits talked with self-deprecating charm about how he could get no recognition from his children other than “they seem to like me as a driver… I take the turns really fast”. And despite his best efforts, hanging around conspicuously in music shops, no recognition came from the music-loving public. Yet when he drove his kids to the landfill, “Twelve guys surrounded my car… Everybody knows me at the dump.”

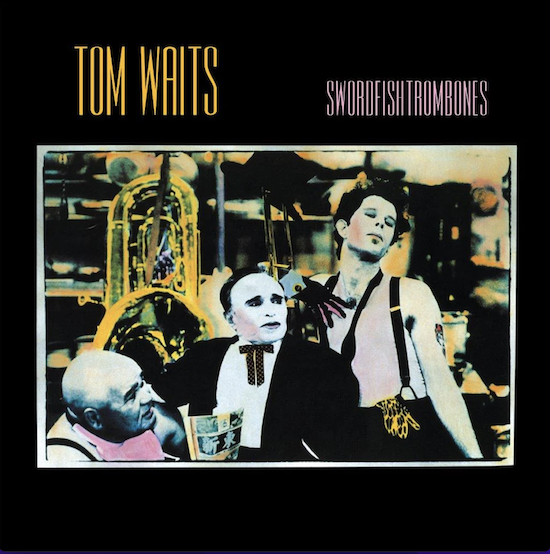

Listening back to Waits’ Island trilogy of Swordfishtrombones, Rain Dogs and Frank’s Wild Years, I was reminded that I was essentially one of those guys at the dump. Listening to them a second time, I realised I’d never left. Neither has Tom Waits. Simply because, in his music and persona at least and with the greatest respect, Tom Waits is the dump. The story of the Island trilogy is how he transformed, from a degenerated piano man of a New York City damned to forever repeat a single autumn night in 1955, to a very different creature indeed – a clattering magnetised bionic man pulling in detritus from every landfill from Fresh Kills to Laogang. Where once Waits had dealt in self-conscious standoffish cool and the plausible deniability of irony, now he was dilapidated and inflammatory and misanthropic, no longer smoking in doorways with collar up, newsboy hat down, amidst the drowning neon, but instead marauding through the streets of every port, a junkbot-golem, mechanical and rhematic, pulling himself in a hundred unanticipated and brilliant directions at once. How had this happened?

The difficulty in escaping a condemned path is that it often works so well. All that’s required is to simply continue, change nothing, repeat until the diminishing returns run out and luck follows suit. By the early eighties, Tom Waits had built an impressive body of work – albums like Small Change and The Heart Of Saturday Night – but it was apparent something was off. The problem appeared to be his schtick. It’s certainly not difficult to find the bathos and schmaltz in Waits’ early songs (even in his finest like ‘Martha’ and ‘Tom Traubert’s Blues’) or point out that his position as a psychopomp to New York’s underbelly came from choice and not necessity, unlike many of the real-life versions of the protagonists and bystanders of his songs.

Yet early Tom Waits was a performer and so he performed, often with tongue-in-cheek, a role that was demanding; he lived the hard-drinking nightclub life, after all, for many years. It was a far weirder position than it may have seemed. This wasn’t just another coked-up Laurel Canyon singer-songwriter or half-baked Dylangänger. This was a twenty-something who sounded like an eighty-year-old, staggering around inside an Edward Hopper painting, whistling In the Wee Small Hours of the Morning to himself, an artist who hadn’t seemed to have noticed or been told the Sixties had happened. Viewed in a certain light, this was outsider art. The problem wasn’t the schtick, which exists for all artists, consciously or otherwise. The problem was timing, context, relevance. Waits’ New York City was always partly mythic but in an age of Basquiat and Travis Bickle, the New St. Marks Baths and CBGBs, no wave and breakbeats at block parties, it was fading into the realm of history and he into a heritage act.

Another problem was trajectory. The likeliest routes ahead for performers like Waits – hedonism, wit, piano ballads in strip joints, no eye-contact and a treble whiskey on the rocks – were sadly self-parody or self-destruction. Some of Waits’ strongest influences like Jack Kerouac managed both. It wasn’t even a route ahead. It was a spiral, as Waits acknowledged, bemoaning that he felt like he’d nailed one of his feet to the floor and was doomed to move in circles.

And then it all changed. Swordfishtrombones appears to be as the fracture point, marking the schism between the Waits of before and after, but in fact the split had already happened. The clue was a subtle one, and was to be found on a quiet corner of his last Asylum record Heartattack And Vine. ‘Jersey Girl’ was all heart. One of Waits’, or anyone’s, finest love songs. It had that early hours lullaby sound Lou Reed managed to capture, via opiates and Dion, on the Velvets’ third album or Coney Island Baby. The song was dedicated to Kathleen Brennan. The great schism in Waits’ life was her. The rupture was falling in love. She made him the artist he was to become.

It seems an incredible risk to jettison everything and everyone from before. Yet the safe harbour Tom Waits had been nestling in wasn’t safe anymore. He couldn’t stay. Brennan gave him the courage and the wisdom to venture out on his own. Gone were the skilled collaborators like Bones Howe who gave his early albums such a lavish sound. Gone too were Asylum Records who took one listen to Swordfishtrombones and dropped him from his contract. Waits was free, free to sink without trace if the gamble didn’t pay off but free nonetheless. He assembled a coterie of brilliant leftfield musicians and signed a deal with the more maverick Island label, but all depended on the album’s reception. The timing was everything. The puritan revolution of punk had altered so much of the musical landscape, ushering in the period of remarkable reinvention that was post punk, like a controlled burn to make the soil more fertile. In the last act of his old guise, the soundtrack for Francis Ford Coppolla’s much-derided One From The Heart (where he’d met Brennan), Waits had shown he’d already obtained another secret weapon – restraint. It was there on the track ‘You Can’t Unring the Bell’. And it was there on ‘Jersey Girl’. If a musician learns the power of restraint, they’ve a good chance of mastering dynamics and know how to unleash its wild opposites. Which is precisely what Swordfishtrombones did.

Abandon all good taste ye who enter but that’s what’s required to make something actually radical. ‘Underground’ is the way in (and the immediate exit for the faint of heart). A rickety basement door, no sign, an ungodly light behind it and the music, a strange lurching shanty. Waits is less a singer than a master of ceremonies, his voice a bellow, rasping of a hidden world of troglodytes below our own that is simultaneously inviting and threatening (“they’re alive, they’re awake while the rest of the world is asleep”). The strings of the pizzicato guitar about to snap or slip out of tune. The band seconds from implosion but hanging together. Listened to at the time, with a previous knowledge and love of Waits’ work, the first thought must have been, ‘What the fuck has this guy done to his career?’ A question that, creatively at least, is not asked nearly enough.

‘Shoreline’ confirms this was no aberration. The descending guitar line takes us further down into a hollow world, unmistakably urban, unmistakably nocturnal but elsewhere, no longer New York pastiche but Hong Kongs or Bangkoks not quite of this planet but some other. There are traces of the old Waits for sure, but the dial is turned up so high, it’s all distorting, warping, no longer a street performance of verity, more fantastical, almost sci-fi R&R, a gutter form of magic realism.

To find the right direction, Tom Waits had to go wrong, excessively, extravagantly wrong. To find something true, he had to wholeheartedly embrace fiction. Learning what not to do was essential as was the importance of not being earnest. With playful vandalism, Waits had to dissemble his tired over-composed persona and the cloying need for authenticity behind it (there are few lies as duplicitous as sincerity), which often led to mawkish outcomes. Swordfishtrombones was thus the sound of an artist unlearning bad habits, resisting comfort zones, and opting instead for surprise, invention, instinct and intentional disorder. It took considerable effort and skill, aided by exceptional musicians, to conjure up a whirlwind but that’s what it sounds like. Every so often, the eye of the storm would pass over the listener and the few moments of calm would be filled with quiet openhearted romance, as with the gorgeous Brennan-tribute ‘Johnsburg, Illinois’, before the tumult began again, as if to implicitly demonstrate the shared shelter of a relationship in the storm that is life.

At the centre of this whirlwind too was the new character Waits was building around himself, that clattering metallic scrapyard scarecrow. He’d kept pieces of his old self but now they were indistinguishable from parts that he’d refashioned and cobbled together from elsewhere, namely from vast listening habits. The sources were divergent from one another, but all shared a sense of being on the peripheries, whether they’d been discarded, forgotten, just emerging, long marginalised or deliberately planted themselves there – Howlin’ Wolf, Harry Partch, Brecht and Weil, Thelonius Monk, The Pogues, the Brothers Grimm, Captain Beefheart, Skip James, Agnes Burnelle, William S. Burroughs, Gavin Bryars…

The musical forms too were not necessarily contemporaneous, in the Western zeitgeist at least, and had a similarly left-behind feeling. There was richness to be found in the apparently redundant, and few around clever enough to mine it. Junk was not junk at all but treasure and relics from the deepest of places that fashion had hubristically disregarded – klezmer, cabaret, rhumba, polka, muzak, bossa nova – and with them certain then-underused instruments that they utilised to great effect – bagpipes, glass harmonicas, banjos, pump organs, trashcan percussion, and above all marimbas, landing like rain on circling ripples. The originality of Waits’ new sound was partially due to the multiplicity of these influences and their common denominator of otherness. Hence also his cast of characters, most of them dialled up into the grotesque (Ralph Steadman was an acknowledged inspiration) but also the unreliable narrators of many of his songs, bar the ones dedicated to Brennan. From now on, Waits wouldn’t be burning himself out to live up to some image of sincerity, risking health and sanity in the pillories and pyres of fame. Instead, his persona was a hybrid, built from exchangeable parts, which allowed for effective shapeshifting. Waits would play the roles and strike the poses, wear the pork pie hats and the gramophone horns, tell the puckishly tangential stories and embrace the Barnum & Bailey or even conman approach, offering a choice of faces to sell you.

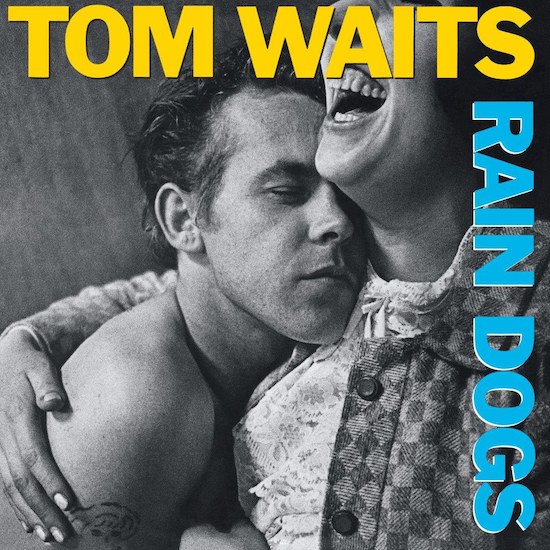

It was with the release of Rain Dogs that all doubts and chance of retreat were dispelled in what may be the strongest collection of his career. The alarm raised by Swordfishtrombones had died down, but the weirdness remained (see the street-level gargoyles of ‘Cemetery Polka’), albeit balanced with ballads that felt genuinely wise and lived-in (‘Hang Down Your Head’, ‘Time’), rather than the artificially-wizened songs of before. The sense of outsiderdom is strong throughout. The title refers to hounds that had their scent of home washed away by downpours and spent their days lost and wandering, dogs with whom Waits has a convincing affinity. The cover of the album was perfect too – a snap of ecstatic disrepair from Anders Petersen’s Café Lehmitz series, taken in the red-light district of Hamburg, where the lines are blurred between voyeur and devil-may-care participant, and between life-affirming abandon and life-shortening decadence. What makes the photo series (and the album) so fresh still is its spontaneity and absence of moralism. Rather than romanticise or condemn, you are thrown into the midst of this world. It’s music you can dance to (‘Jockey Full Of Bourbon’) or lament to (‘Anywhere I Lay My Head’). We’re no longer told the piano has been drinking, we can hear it (‘Tango Til They’re Sore’). The contemporary obsession, now, of art as a tool is refreshingly absent, and so too is the stifling tyranny of intention. Instead, this is art as location and immersion. Rain Dogs makes it clear that this trilogy is partly a travelogue, even if the places visited are semi-imaginary, from the disorientated orientalist vision of ‘Singapore’ to the crazed A-train of the mesmeric ‘Clap Hands’, charismatically pitched to you by someone rifling through your pockets. It’s a ragged masterpiece.

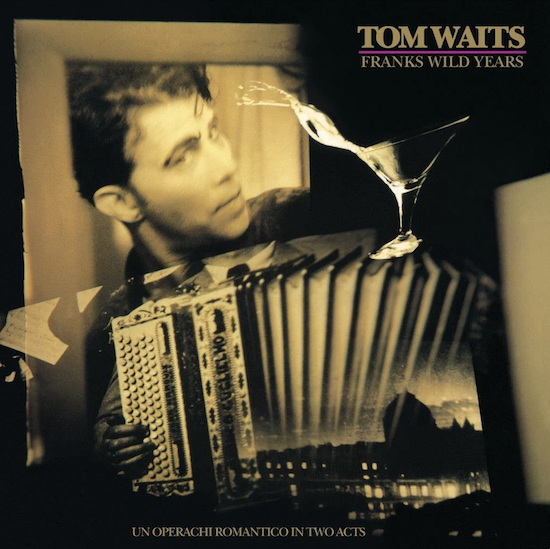

A consummate album by anyone else’s standards, Frank’s Wild Years feels less like the third instalment of a trilogy and more like a minor satellite of two much larger worlds. Its songs are fragmentary and point the way to the future in good ways (fractured theatrical peaks like Alice and Blood Money) and bad (slipping into new comfort zones like smuggling 12-bar blues under clanging metal and megaphone hollers). The engine here, like all Waits’ work to follow, is powered by the tension between chaos and solace, though its finest moments are its most oneiric, the ones that sound like fairground farewells recorded during some secret decade of the 20th century – ‘Blow Wind Blow’, ‘Innocent When You Dream’, ‘More Than Rain’.

As joyfully reckless, inspiring and intoxicating as ever, the Island trilogy marks the moment when Tom Waits found love, quit his previous job and became a collector. It didn’t matter what he collected, other than it had to be unexpected. Pieces of language from eerie nursery rhymes to heavy wooden chests tied with etymological ropes. Knickknacks and curiosities. Stories people had long forgotten hearing. Wolf tickets. Broken clocks. Lucky Tiger grooming product. The tarantella. Bathtub gin. Swallow-tail coats. A weathervane rooster. The Rose of Tralee. Now as then, amid all the discarded junk of the world, three crooked trees are somehow growing, and if they can then others might and do and will.