After decades of colonialism, civil unrest and dictatorships, Indonesia has only recently begun to grapple with the question of what to do, post war. With the fall of Suharto in 1998, years of censorship began to ease – and current president Joko Widodo’s election in 2014 sparked a huge Internet boom in distributing knowledge and power. For Aditya Surya Taruna, otherwise known as Kasimyn, one half of Gabber Modus Operandi, that question has taken up the better part of a decade, and has resulted in his solo project, Hulubalang.

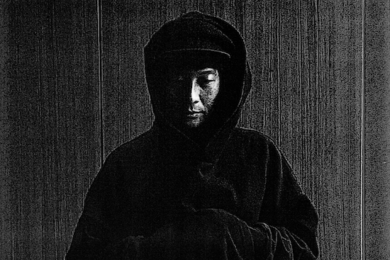

Long before he teamed up with Ican Harem to form GMO, Taruna had been mulling over ways to emotionally respond to what he calls “the mess of the archive”. Throughout his life, Taruna had visited many war archives, like the War Remnants Museum in Saigon, Vietnam. “I would check the credits of the pictures, and most of them were anonymous.” It was a visit to the Tropenmuseum in Amsterdam, The Netherlands, where Taruna’s mission became clear. It’s where he encountered the album’s cover art, whose caption only read: some man from East Java. “That’s it,” he says, resigned. “This guy was somebody’s parent, somebody’s grandpa. It became a commodity for my anger.”

Today, he’s smoking cigarettes and enjoying the sun in Bratislava, where his wife’s family is from. Taruna finished Bunyi a few months ago, and is contemplative and careful when it comes to the intent of his work. Bunyi Bunyi Tumbal is his newest album, a reflection on the legacy of war in Indonesia. There are certainly conflicts both political and personal embedded in that, so when Taruna claims that the album is not “political”, it can be rather confusing. To understand how that’s possible, you’d have to look at how modern Indonesian society views the wars. Taruna generalises that there are two major camps: those who demand some sort of apology or reparations, and those who want to accept the war and start forgetting. “People also have the right to forget things if it’s painful.”

Indonesia as a nation has undergone several periods of colonisation – most notably from the Dutch and Japanese – but even beyond that history, there are tense relationships between ethnic groups. Growing up in the district of Tanjung Priok in North Jakarta, Taruna is descended from an ethnic Chinese lineage on his father’s side. The group has faced severe targeted violence over the years, most notably in the May 1998 riots, where over 1,000 people lost their lives. That background has profoundly affected how his family has processed their history: “We don’t talk about it, we shut it down.”

So perhaps that’s what influences Taruna when he says: “The media seems to have this tendency towards preserving old stuff. I don’t care about that. It’s already destroyed. I care about my curiosity about how their feelings might have been when it happened.” Even in that statement alone, it’s telling that Taruna is too inquisitive about the past to forget about what happened. In fact, that speculative aspect of his artistry has seeped through GMO’s work, imagining the possibilities of Indonesian dance music away from the strictly commercial demands of outsiders. As Hulubalang, Taruna is interested in a future liberated from modern politics, its consequences, and its connotations.

“Let’s say there’s a village in my hometown in central Java,” he explains. “They don’t have any political or religious affiliations. Then the colonisers come. Then, from the city, the big powerful smart academics come, saying: ‘We need to be against the government, because they’re repressing us.’ In the end, the village doesn’t want to be part of anything; they don’t care. That’s what I feel, because at the heart of things, I’m an anarchist.”

Don’t be tempted to slap a capital A for Anarchy on Bunyi, however. He is explicit in his assertion that the album is not supposed to bear a political stance. “I don’t think it matters for a Western audience to dig deep with this, because it’s so personal for me that it doesn’t reference popular politics,” he explains. “I don’t want it to be an ‘oi punk’ album, or an ‘electronic, left-anarcho album’. It’s more about feelings.”

That also applies to his project name, Hulubalang, which was chosen for two reasons. One: it captured the complex political nuances of Bunyi. Hulubalang were both territorial rulers and warriors from the 1500s onwards, and were most notably active during the Aceh sultanate. Though they technically operated under the Sultan, they also had some of their own independent power – in some areas of West Sumatra, Taruna says later over email, they’re considered anarchic. They fought the Dutch until the last Aceh sultan surrendered at the end of 1903, whereupon they switched loyalties and ruled under the Dutch and Japanese colonisers. The Cumbok War (1945-46) ended the era of the hulubalang; shortly after, many were executed without trial, people believing they had abused their independence. “They’re not really heroic, but they’re also not enemies. They’re inbetween.” He also used the name, he smiles, because “the word is catchy”.

The emotion that was trickiest for Taruna to capture was that of innocence, imagining a world before it was touched by history. “I’m not romanticising it, but I have a lot of curiosity. This thing is so far away from me, but it’s so familiar – the face, the shape, the nature, the expression.” In order to access that world, Taruna dug back into tradition to excavate buried emotions. “Popular music is always in major and minor keys, but 100 years ago, more than half the world didn’t know that shit. What kind of feelings did they have back then?” he wonders. “My grandpa definitely didn’t go, ‘Oh, I feel sad, I’m going to play a minor key’. The feeling is completely obsolete for them.

“Don’t get me wrong, I love blues, I love emo, but if I listen to traditional music, I find there’s a layer of feelings. It’s a crazy territory that I can’t find in modern music,” he continues. “Listening to Burundi vocalisation, or Bulgarian, I’m like, ‘What the fuck were they thinking and feeling?’ It’s so weird and interesting.” He refers to death rituals in particular, saying that death is more celebratory in Indonesia, and the sounds of gamelan singers attracted him. In a tourist area, the singers merely sound “ethnic” and “cultural”. But listening alone? “It sounds fucking creepy”.

On other songs like ‘Tunkai’ and ‘Buddakawan’, he relied on the unique harmonics of Indonesian music, pitching up vocal samples so they didn’t neatly fit within the octave. But in most cases, Bunyi was the result of pure experimentation: “Most of it comes from having fun, not in a conscious, ‘I know this theory’ – not at all, I’m not that smart,” he jokes. “Just, ‘Oh shit: this sounds interesting…’”

Taruna is also interested in the potentials of distortion, both as a sound and a concept, and it’s particularly salient when applied to his thoughts on postcolonial identity, something which he credits to American philosopher Wendy Brown. “It’s not about self-claiming whatever happened in the past, but destroying something for the future,” he explains. He’s speaking from the perspective of GMO, but it rings true for Bunyi, too. “The beauty of this new world is when the marginalised are empowered by technology, they can decide whether they want to preserve or destroy. The best thing is actually when they’re destroying. If you’re destroying the perspective of the culture, it’s destroying the idea of how this culture will be built in the future.”

He continues: “This conversation of ‘are we preserving this?’ – this wasn’t happening to European artists. ‘Are you gonna bring back classical music?’ They hate it already! I’m not saying Asians need to hate their culture, but it needs to have a free interpretation of what this can be, rather than just ‘oh I love traditional music, it’s so spiritual’. Everyone can do whatever they want.”

On the one hand, Taruna wanted to be true to his feelings, and on the other, create a future without necessarily erasing the past. It was a delicate, specific brief he had set himself, and he struggled for several years to fulfill it – that is, until Björk came along: “If I didn’t work with Björk, I don’t think I could have finished this album”. GMO had been enlisted to help produce several tracks on her most recent album, Fossora, one of which was ‘Atopos’. It is a record that channels the grief of her mother’s death and pandemic-induced isolation into a plea for hope and connection. When you listen to ‘Atopos’, it isn’t hard to imagine how those lyrics may have helped him deal with the thorny issues of his own project: “If we don’t grow outwards towards love / We’ll implode inwards towards destruction”.

“Björk is close to the Buddha for me – and I’m a full-blown atheist,” he jokes. “The first time I got the files from her, I was like, what the fuck? But once I wrote ‘Atopos’, I had a clear mind: this is how I should finish. Back then, I worried so much about Hulubalang. I didn’t even think it would be released, I made it personally for myself. I thought it was some artsy bullshit mentality that nobody would understand. What I learned from her is that as long as you can articulate it and you know how precise things can be, you can do it as weirdly as Fossora.”

It seems that the answer to Hulubalang’s question, of what to do post-war lies in acceptance; Taruna has found his own way to say that perhaps the most valuable course of action is nothing at all. “I don’t want people to use this narrative of: I’m going to listen to this because I want to support ‘the cause’,” he says. “There is no fucking cause, and even then, the cause is done. The only thing you can do is whether you like [the album]. There’s nothing I or the listener can do about this.

“And it’s not nihilistic: I actually find it optimistic that I, of a certain historical, political and cultural background, can make art out of it; to embrace that these things happened. I can live with it and move on."