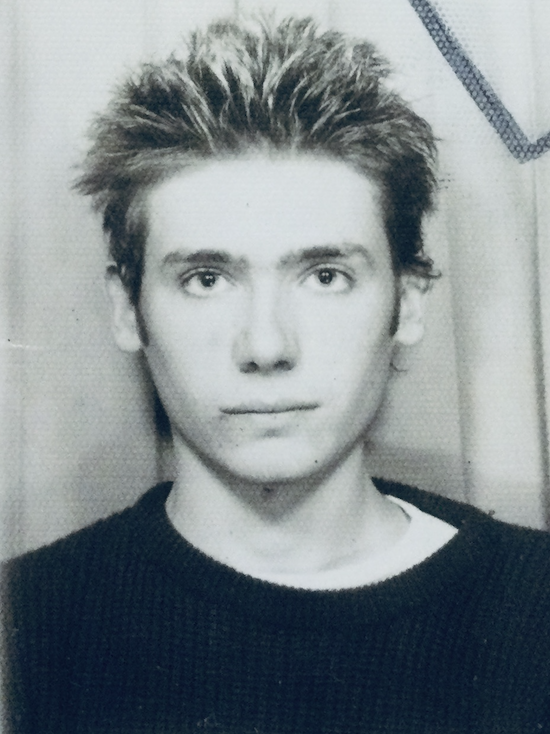

When you interview implausibly tall Monmouthshire musician Nicholas Allen Jones, the second the round red icon on iPhone notes is tapped or the record button on the Zoom H6 is clicked, a large pair of sunglasses appear on his face. Regular as clockwork. I’m not even sure where they materialise from. It’s at this moment he becomes Nicky Wire; or that used to be my guess at least. I assumed it was, in some respects, the temporary adoption of a rock star archetype’s carapace, a protective shield from behind which he was able to say the things that needed to be said – the things that perhaps bookish Nick from Blackwood might baulk at. A tactic that allowed him to think, ‘What would Nicky Wire the famous and outspoken musician say when asked a question like this?’

Today, in a nice hotel room in Bath, before a Manic Street Preachers fan club-only Glastonbury warm-up show, there is a lot of light streaming through the townhouse-sized windows and I can see that for much of our talk he has his eyes tightly closed behind his shades. So perhaps it’s not so much a strategy for keeping the process separate from his daily life as it is simply a way of concentrating on what he’s already decided to say.

He’s a funny guy, to the extent it’s very easy to miss the essentially downer nature of a lot of what he says as he says it. He’s erudite and uses about ten different words for melancholy in 90 minutes, again, dissipating some of the immediate negative implications of the conversation somewhat. He’s good company and very engaged with the process of being interviewed but there’s no banter, no wild off the cuff jokes that are going to come back to haunt him years later, no formulating new ideas or positions in real time. And certainly, as he acknowledges at several points, there’s no desire to bad mouth other famous musicians and no small amount of contrition for the occasions when he did. Times have certainly changed.

As well they should. He’s older now of course, even though he’s still probably the most striking looking 50-something in the majority of the rooms he walks into. He’s formulating different processes to cope with the ongoing physical and mental stresses of someone firmly in middle age yet still playing a relatively demanding role in a very popular rock band. It’s during the aftershock of entering your sixth decade that it becomes clear the sad and stark realisations of your middle years aren’t going to resolve themselves; all of that hectic ‘mid-life crisis’ energy and darkness doesn’t go anywhere. It hangs round like an unwanted house guest, looking through your cupboards for Bacardi and crisps, firing up Netflix. “It’s unshiftable”, he says at one point.

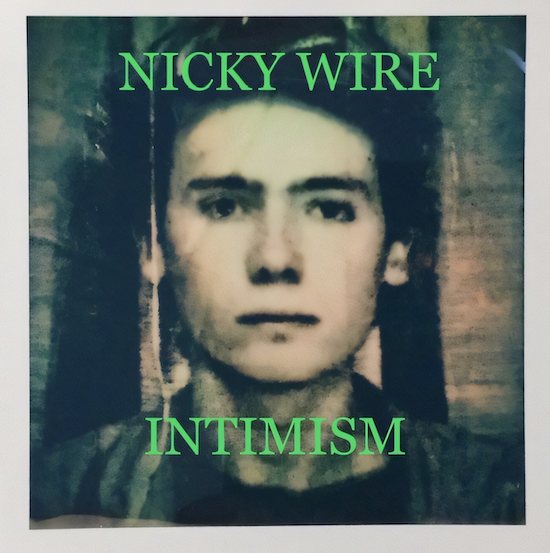

A sometimes self-deprecating, sometimes bolshy, sometimes beaten down expression of this realisation about ageing – an acceptance that your life has reached its terminal velocity – informs, infects, amuses and salves at various junctures on Intimism his excellent new “low-key” solo album, the follow up to 2006’s I Killed The Zeitgeist. The irony being that this is clearly a very well-executed, twelve-years in the planning strategy against melancholy. Or, to be more precise, a strategy to integrate and accept melancholy afresh, to embrace it, as if it were an old friend, while writing and singing ruefully about how it intrudes remorselessly into every nook of his life like a blinding headache.

There are two tracks on Intimism with the name ‘Migraine’. The first of these slinks along on a bed of hissing percussive metal, with wandering bass and an angular guitar striking odd chords, all of which really provides the loose framework for a sun-scorched soloing trumpet locked in battle with a heavily muted twin. At the very least, we’re very knowingly being put in mind of ‘electric’ period Miles Davis, specifically Bitches Brew, and more specifically again, the tar-black throb of ‘Spanish Key’. On the second of these tracks brass man Gavin Fitzjohn returns on trumpet but this time there are a number of different takes that have been spliced, edited together and layered on top of one another. Over the top of this psychedelic jazz fusion bed, Wire chants lazily: “Nicky Wire is no more, he’s lying face down on the floor. His knees are fucked, his back is sore, his face parades a thousand years, his mind is numb, it’s full of fear. The makeup is a-runnin’, the tears they are a-comin’.” The keyboards ape a shattering crystal vibraphone and as the track boils over into blown out noise, the intrusion of vivid guitar licks can’t help but make you think of Mahavishnu Orchestra’s John McLaughlin; in spirit at least.

Usually when indie bands ‘go jazz’ they are not altering the structure of what they do – as good as tracks like ‘The National Anthem’ by Radiohead and ‘MBV Arkestra (If They Move Kill ‘Em)’ by Primal Scream genuinely are – it tends not to go further than temporarily drafting in outside musicians to sprinkle a jazz vibe over the framework of a more traditional rock song. ‘Migraine No1’ was free-improvised live in the room as a band, while ‘Migraine No2’ was, more in keeping with a Bitches Brew-mindset, arranged and edited from a number of different improvised takes. Nicky Wire was, for that afternoon at least, his own Teo Macero. Although he puts it this way: “I felt a bit like Captain Beefheart: instructing musicians while having no musical knowledge myself.” Naive these tracks may be, but they’re definitely not indie rock. Speaking as someone whose copy of Ted Gioia’s How To Listen To Jazz sits defiantly half read on his book shelf, I’ll leave it to someone else to pontificate on whether this is good or even allowable jazz but I do feel qualified to say this much: it’s thrilling in this context.

Hang on a second… Free improvisation? ‘Spanish Key’? John McLaughlin? Inner Mounting Flame? Teo Macero’s editing techniques? There’s no time for niceties. We’re getting into the tough questions right from the get go! Nicky Wire, why have you gone jazz fusion on your new album? “This album is a mosaic. Some of it is 12 years old. And 12 years ago I was going through a huge John McLaughlin phase. I was listening to a lot of Mahavishnu Orchestra. I would annoy everyone with Bitches Brew side two on playlists and in the dressing room. The way Miles Davis moved into rock and created something completely new and unhinged… his band really didn’t give a fuck. Even though the playing is off the scale, it’s just really stroppy music.”

Some of the other musical touchpoints for Intimism such as Big Flame, A Witness, even Go Go Penguin, don’t initially seem congruent but there is a through line: “James [Dean Bradfield] was always banging on about Big Flame and I could never understand it. But then I played a record of theirs at a slower speed by mistake on vinyl once, and suddenly I got the jazziness of it.”

I’m only part-joking when I say I suspect that his solo career has been designed by committee to syphon off influences that could be disastrous to the ongoing trajectory of Manic Street Preachers, and I’m unsure how serious he’s being when he laughs: “That is 100% correct. It’s such a big juggernaut just coming down here to Bath and then on to Glastonbury, setting up the visuals, the sound checks. I’m not saying we’re the biggest band in the world but it’s still a massive vehicle to get going. I wanted Intimism to feel like it was less committed, more casual; but I did want to feel like it contained all of those things that are not needed in Manic Street Preachers.”

The Migraine tracks are not musical degeneracy, thoughtless dilettantism or a trolling of longtime fans though. As the word suggests, Wire is trying to conjure up a synaesthetic, dissociated feel of its namesake neurological condition: a sense of “being broken” by migraine. He is at pains to say he’s one of the lucky ones as far as sufferers go but these events come, approximately, once every three months with intense visual distortion, nausea and an incapacitating headache lasting for two or three days; the sum being a “hospital ward feeling”. His strategy for nipping these “cluster fucks” in the bud sounds unscientific, mediaeval almost, but is in the main successful: “I bury my fist in my left eye where they always start and then lie on it”. Then “strong painkillers and lots of ginger ale”.

Full disclosure: leading with jazz experimentation has been something of a misdirection. The rest of the album is anthemic FM rock, arena indie and Americana in its songwriting, while spiritually, and sometimes tonally, in some debt to the spirit of C86; Felt and the (criminally forgotten about) Weather Prophets as much as Wilco and the Pixies. Wire mentions Felt a lot today, as he has done in plenty of previous interviews. Occasionally, in the past this may have been to lower expectations over what might euphemistically be called his bass player’s singing voice, as much as to express fandom. But – without wanting to throw any more unnecessary shade – Intimism is an album he could only have recorded now. No disrespect to the Nicky Wire of 2006 or 2009 but objectively speaking, he’s come a long way vocally since, say, ‘William’s Last Words’ from MSP’s Journal For Plague Lovers. The change stems from “improving technique, singing quieter, tracking more, spending more time singing to myself, writing in a particular range that suits me”. Plus, as he laughs, “With ‘William’s Last Words’ I recorded one take and Steve Albini said, ‘Well, that’s all of the emotion – you don’t need to do it again.’” Certainly why would you do a second vocal take when you could spend an entire half day checking the drums are mic’d up optimally?

His singing voice now reminds him of a lot of the music he grew up with, harking back to an age when he wasn’t “focused on the technical capability to reach notes rather than an image of who the person with the voice was”.

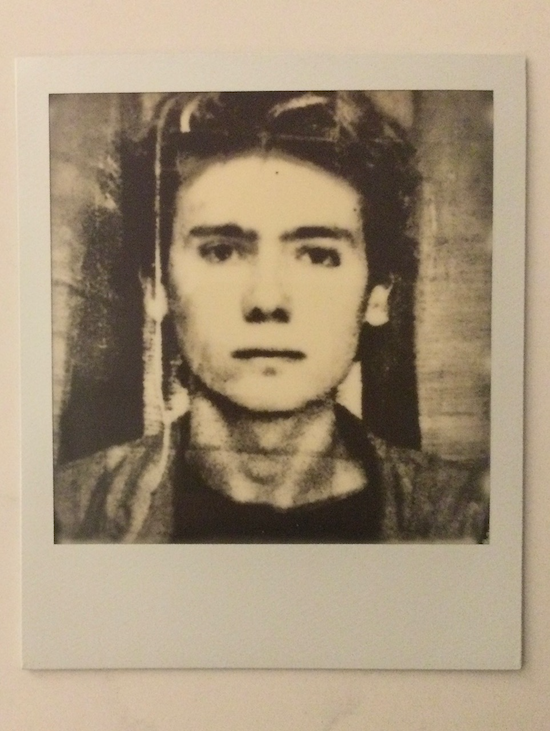

He knows there are plenty of record labels who would have put Intimism out and says it “might have been nice for vanity’s sake” to have it pressed up on vinyl but he’s decided to release it as a digital-only album on Bandcamp via Sepia, in order to keep it “as me as me can be. The bit of artwork that exists is just a Polaroid of me. I don’t want the rigmarole of pretending this album is something that it’s not.

“I’ve just tried to think of myself as a 16 year old, going into [hallowed Cardiff record shop] Spillers – like me and James used to at that age after we’d been busking to raise the money to buy the new record by the Triffids, The Go-Betweens or the Shop Assistants.”

The cover “Polaroid selfie” was taken by Wire while a callow second year undergraduate at Swansea University in the late 80s, and early evidence of a life-long obsession with the photographic medium: “Years ago when on tour with the band, I’d be up at 7.30am and go out around whatever city we were in and take maybe 30 to 50 Polaroids. I wouldn’t really look at them. I would go back to my room and seal them in the hotel envelope. I still haven’t looked at any of them. It’s a kind of art experiment. Those trigger points made a big impact and framed the sense of fragmented memory that set the scene for the album a bit. ”

Sometimes, musicians in Wire’s position want to signal that the press, or perhaps their own fans even, have them wrong somehow. The implication is there are invisible hoops musicians in successful groups are impelled to jump through, so they initiate a solo career as a kind of perception corrective, an acid bath which will strip everything away and reveal the ‘real’ them. And to symbolise this new level of intimacy and honesty they ‘strip away’ all of the frippery and sit at a piano, or dust down an acoustic guitar. Of course, as often as not, this is simply another exercise in obfuscation, another layer of disguise to hide the truth which could be either be too bland (‘I’m worried next year’s tax bill might be too big’) or too thorny (‘I’m irritated by my band mates and sometimes even my family’) or too painful (‘I somehow lost my relevance without even noticing’) for airing in public. So perhaps there is some honesty in releasing an album which is very big and brave sounding, but where there is a marked contrast between the FM-friendly, major key optimism of the music and the melancholy, beleaguered, rueful nature of the lyrics; a dialectic for those still searching for beauty when experience suggests it might now be in short supply. A massive sounding record, about to be slipped out with little fanfare while no one is looking.

He says: “I hate the phrase ‘the authentic self’ because I have no idea what that really means. There was an art movement called ‘intimism’, which included the great Gwen John who I’m a big fan of, and it was about these mundane paintings of the interior, which were made almost holy in their ordinariness. I’ve always been attracted to that because I love the mundane nature of being inside. I can’t tell you how many lovely summers me and my brother had closing the curtains and watching cricket all day long. It was beautiful.

“There’s a line on the album, ‘I’m not a socialist anymore. The social bit leaves me cold.’ I am still a socialist and I do believe in it but I’ve always struggled with the communal, social aspect of it. I see so much excitement and beauty in things like my memory of being 12 and in my room watching Steve Davis get the first 147 ever at the Lada Classic on a black and white TV.”

There are a bunch of songs here that are ’arena sized’ and at least four of them feel like they could have been contenders for Manic Street Preachers-status but apparently they are “too fragile”. MSP singer/guitarist James Dean Bradfield is a fan of the Intimism however and an executive producer, loaning dazzling sunburst soloing to ‘You Wear Your Heart’, slide guitar on ‘The Ballad Of Baby Blue’, bass and extra guitar on ‘Keeper Of The Flame’ and a solo on ‘Tactical Retreat’.

Wire himself played most of the guitar and bass as well as drumming on ‘Perfect Place To Grow’ and ‘White Musk’, while elsewhere the role is filled by Manics studio tech Rich Beak. Another person in the MSP team, Loz Williams is described as a “Mensa-level intellect”, “essential” to the project and being “like Stephen Hawking” when working on music in the studio; he fulfils the role of lieutenant to Wire on Intimism, helping him record and produce the album as well as playing all keyboards and pianos.

Too fragile for the Manics or not, long lead single ‘Contact Sheets’ burrows into the consciousness and is another prism through which Wire can view the past: “I look back at Mitch Ikeda’s photographs of the band because I’ve kept all of his contact sheets, marked up with his chalk pencil. It creates this absolutely gorgeous warm feeling, unlike the cult of digitalism, of scrolling through pictures on someone’s iPhone. Contact sheets are part of a vanishing world. I’m so glad I’ve got all this stuff.”

Wire admits he has become the de facto Manics archivist, something about which he clearly has mixed feelings. From the original chromaline plates of album artwork to original band photographs, he has everything stored “in an annexe” in his house. Does it keep him awake at night? “It keeps my wife awake at night.”

He says he’s a collector rather than a hoarder but before I even have time to interrogate this suspect-sounding statement he blurts: “Here’s an exclusive for you: I do have about 100 flannels from different hotels.” One hundred flannels. One hundred fucking flannels. Even spread over three decades, no one could pass this industrial scale larceny off as an accident, there must have been some nefarious plan: “I guess it’s the nearest I’ve come to criminality. But I am obsessed with both hotel stationary and with being in other places. With the song ‘Sullen Welsh Heart’ I had to go to South Korea in order to finish it. I had to be in a hotel room in the most unWelsh place of all before I could finish this distillation of the Welsh psyche.”

The extent to which Wire has moved into and occupied AOR territory is occasionally as stunning as it is disconcerting. The track ‘Ballad Of Baby Blue’ is both genuinely catchy and vaguely reminiscent of the Travelling Wilburys. I mean, I like the Travelling Wilburys and their genuinely catchy songs, I don’t mind admitting it, but it’s also hard to reconcile this fact with his role in the Manics single ‘Faster’, one of my all-time favourite rock songs, which I hear him playing a superb version of with the Manics later that evening. But this is what happens. Did I find ‘Handle With Care’ hard to reconcile with ‘All Along The Watchtower’? With ‘While My Guitar Gently Weeps’? With ‘In Dreams’? Who can remember that far back.

‘White Musk’ is written for his late mother and her unwavering love for the bright and cheerful Body Shop fragrance: “It’s five years just gone now since she passed away and, you know, for all my self-loathing and lacerating reappraisal of regret, the one thing I wake up every morning and think is that I was so lucky to have my parents. I would always want to buy her Chanel or something but she was always like, ‘No, no, I like White Musk for Christmas… and Tweed for my birthday.’ [laughs] My parents’ relationship with our music was really important. They were so encouraging. As were James’ parents. The money we needed to record [debut single] ‘Suicide Alley’ was given to us by them. We would never have gotten anywhere without that. My parents really enjoyed me being in a band – not in a show off way, but if it ever came up in the supermarket she couldn’t wait to bring it up. I can’t tell you how lucky I feel really. There are a lot of horrible backstories out there, but mine simply wasn’t.”

It’s during ‘White Musk’ that one of the unifying thematic structures of the album is easiest to discern: “When my parents died, it took me and my brother two years to clear the house. At times we couldn’t even go there due to the lockdown. There were so many lovely things to go through it felt like a tactile archive of our lives – the actual substance of what made us the people we are today. The house bound us together so tightly it was kind of heartbreaking to leave it and I started questioning if memory can survive the loss of losing the physical entity that helped make the memory itself. A bit high concept I know.

“Our childhood school has been knocked down; the school that me, James, Richey and Sean went to – and Joe Calzaghe, Britain’s greatest ever boxer – and now there’s literally no trace of it left. And Sound Space Studios, in Cardiff, where we recorded The Holy Bible? Fucking flattened. So I was asking, ‘Is it just the cognitive memory that remains after the place has been smashed to bits? Or is there something else?’”

On the breezy ‘California Skies’ – as much a nod to Glen Campbell as it is Wilco – there is a reference to the Manics saying at the Roosevelt Hotel in LA, with its decadent Tropicana swimming pool decorated with a David Hockney mosaic. It was 1992, during the band’s first tour of the States, just after the riots. Wire was already beginning to feel that they had lost their way both in failing to break the States and also temporarily abandoning their British roots for a more Americanised hard rock sound, which would become most audible on the following year’s Gold Against The Soul: “The idea of America was obviously very big for us. I think the trouble was, in many ways, it was really easy for us in the UK because there was a route we could follow. It was: get a piece in the music press, then get a cover, then get Radio One and then get Top Of The Pops. And we actually did it in eight months with ‘You Love Us’. And then we went to America and realised that there was no pathway other than endless gigging and talking to people; and the press wasn’t to the same standard as it was here. It really wasn’t. And me and Richey not being able to play? It didn’t matter in Britain, but when we got to America it really did matter [laughs], so there was a lot of pressure on James and Sean to carry us.”

Of course, this is not to say they don’t have a sizable cult following in the States. Recently the band enjoyed a “magical” co-headline tour of large theatres in North America with Suede where he was blown away by how rejuvenated the other band have become since reformation, but the suggestion remains that it wasn’t a jaunt that either group could have undertaken on their own. If ‘California Skies’ is a song of regret over not ‘conquering’ America as a younger person, he is nothing if not philosophical now that he’s older: “Failure is such a huge part of being in a band. Without it, bands are just on a linear trajectory of boredom. We’re about to reissue Lifeblood, which was a catastrophic failure at the time, as was The Holy Bible, but without them we’d be such a lesser thing.”

If Wire sounds like he’s somehow resigned, it’s not true though; there are always strategies, outside of MSP, outside of Intimism: “I’ve been writing. I was watching a documentary on Paul Bowles in Tangiers – my wife thinks Sheltering Sky is an absolute masterpiece, and she reads a lot more than I do – and one of the themes was automatic writing. So I thought, ‘Fuck it. I’m going to write a book.’ And I feel like I’m cleansing myself through that process. I set myself a target of so many words a day. I’ve got a good title, Modern Fragments. It’s a long essay. An interior monologue. No characters. There’s a chapter on the glory of bin night; a weekly peak of excitement for a man in his 50s. There is relief that the recycling is done, and when the council come and take it all away the next morning, it feels like a tiny but amazing victory. And I think having tiny victories in your 50s is important because you don’t get to have the big ones.

“I’m just trying to navigate things. I’m anti- that sentiment of ‘What journey have you been on?’ I don’t fucking know. ‘Are you living your best life?’ I don’t know what that is, I’m just trying to fucking keep it together.”

And this is also not to say that there isn’t energy left for the project. He reveals they now have 12 songs written for a new Manics album which should see the light of day next August. He doesn’t want to dwell on it yet for obvious reasons but describes it as “really fizzing” and “uptempo” with a working title of Critical Thinking: “I don’t know where we get the energy from; it’s not particularly easy being in the band when we’re all juggling so many things. We’re all diverging. It’s so easy to lose patience with people when you get to your 50s and we do with one another now. But 15 albums in 30 years. We’re powering on. Like with Mark E. Smith it became just about the work in the end. And that’s fine. I’m trying to reach that rather than the energy becoming about everything else.”

He’d like to do a one off solo show for Intimism in theory, but there are no plans to play it live at the moment, and certainly none to tour it. It’s a shame as these songs are begging to be played live. It seems dank memories of previous solo shows might not have faded enough for comfort quite yet: “I did a couple of shows during I Killed The Zeitgeist – I was drinking then – and they were horrendous. I remember playing the Hay Festival and people were just flooding out of the doors while I was stuck in this monologue about Italian wine. It was… unnecessary.”

Although never a “gigantic” drinker, he quit for good 12 years ago. When you don’t drink for a long period, thankfully, I’ve found at least, it eventually becomes second nature. I no longer think or dream about alcohol. But I do occasionally resent not having the quick fix means of thinning the veil, of loosening up mental channels, of conjuring the sublime, of easily sprinkling some magic across the quotidian. I mean, not everyone can fit things like meditation or a new spiritual practice or psychedelics into their lives, so how does Wire deal with that absence? “It’s a really good question, because I do absolutely miss that feeling of slight abandonment of the senses. I do miss it. I just remember being absolutely hammered in Glasgow and writing the lyrics for ‘It’s Not War, Just The End Of Love’. I just scratched them out on a hotel notepad without even having to think about them too much before I went to bed. I miss it. There’s too much going on… buzzing away in my head. It’s not particularly healthy. And my only way of shutting down is either via nature, or being stuck in the house watching TV or listening to Radio 4. And it’s been like that for a long time.”

But this is starting to feel slightly too rueful, surely there’s a therapeutic aspect to the making of melancholic art? Or does it just exacerbate the situation? “It allows you to embrace it. I’ve come to realise anxiety is an absolutely natural part of being, and denying it is probably worse than realising it exists and then having to deal with it.

“When the Manics started I believed the Kierkegaard maxim about anxiety being freedom. I don’t necessarily think it’s freedom anymore but I think it’s unavoidably present in everyday life.”

And with that, the glasses come off.