She’d seen it on TV, way back in 1967, when she was nine. A hand coming through the window. A child-like spectre whispering. A scene from the BBC’s adaptation of Wuthering Heights. She’d always been into “that sort of thing”.

Ten years later in the top floor flat of a Victorian house, located at 44 Wickham Road, Brockley, random childhood viewing is spun into musical gold. It’s a March evening. The curtains are wide open and Kate Bush keeps gazing at the full moon, sat at an upright piano, a £200 second hand purchase from Woolwich. Soon she’s lost inside a new song with a circular chorus, becoming the ghost of Catherine Earnshaw. To get the details right she reads Emily Brontë’s 1847 novel, and some are already there (“so cold… let me in your window”). Other strange coincidences and synchronicities draw her deeper in. She shares the author’s birthday, like the novel’s headstrong heroine, everyone used to call her Cathy too, Cathy with her “queer dreams that alter the colour of her mind”.

During that summer of 1977, it is recorded at AIR studios, four storeys above Peter Robinson’s department store, and the hustle and bustle of Oxford Circus. Clustered around her at the Bosendorfer Grand piano, session musicians’ jaws drop as she plays ‘Wuthering Heights’. Producer Andrew Powell’s arrangement adds twinkling textures, from his celeste to Morris Pert’s crotales (a disc-shaped glockenspiel). Earthier elements come from Powell’s melodic Fender Jazz bass lines, Duncan Mackay’s organ and Stuart Elliot’s drums. An elegantly sweeping 18-strong string section, joined by three French horns, wraps itself, like gathering mist, around the final masterstroke, Ian Bairnson’s double-tracked Les Paul solo.

At the centre is Bush, ivories spiralling octaves, settling once her unearthly voice enters, high as a hovering phantom, full of scary, seductive conviction. She nails the master take in one complete performance, later saying “When I sing the song, I am Cathy.” It baffles and beguiles. Rhapsodic melancholy full of major chords, tightly organised hysteria, an oddity that’s oddly anthemic.

It was another song cut for Bush’s debut album, The Kick Inside. The inevitability of destiny hangs over its overnight mixing session, engineer Jon Kelly carefully working the faders of AIR’s spangly Neve console to get the balance just right. Spurring things on, “drinking everything up” is Bush, already working out the dance routine, making notes so she can one day oversee production.

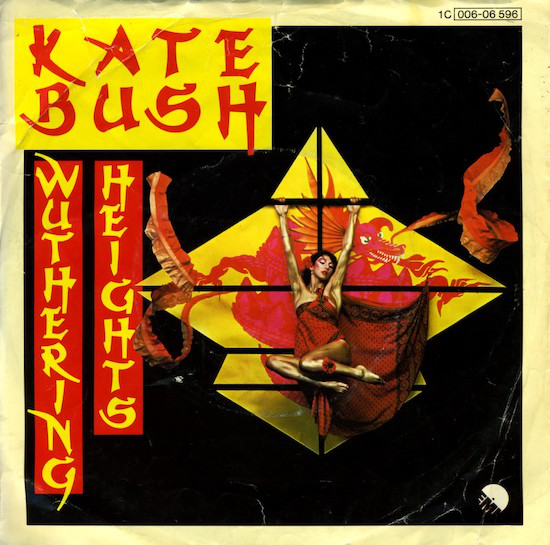

As winter sets in, it starts working its magic. EMI want ‘James And The Cold Gun’ to be the debut single, Bush wants ‘Wuthering Heights’. The label caves in, convinced it’ll take a few albums to break her anyway. Scheduled for a 4 November release, Bush is unhappy with the sleeve shot of her in a pink leotard. Taken by veteran photographer Gered Mankowitz at his Great Windmill Street studio, the image will soon be plastered across buses, underground stations and empty store-fronts. But a more subtly sexy Kate, clinging to a kite, will grace ‘Wuthering Heights’ eventual cover. Fears that it’ll get lost in the yuletide frenzy push its release back, as ‘Mull Of Kintyre’ climbs to the festive top spot.

Most radio stations agree not to play the demo copies already sent out. One exception is Capital’s Tony Myatt. Before ‘Wuthering Heights’ hits shelves, it casts a spell across the airwaves, entrancing and irritating listeners; melting hearts, jangling nerves, stopping them dead in their tracks – many picked up their phones to demand another spin. Reviews will be equally polarised; “bizarre” says Ian Birch of Melody Maker, “mesmeric” says Bob Woffinden at NME, “rotten” judges Rosaline Russell from Record Mirror – the diversity of opinion, that for Bush hero Oscar Wilde, reflects a new, complex and vital work of art. The Brontë society thinks it’s a “disgrace” but John Lydon loves it (although his mum thinks it sounds like a bag of cats). It’ll finally arrive in record shops 20 January 1978, just days after the Pistols split.

It starts to climb. Number 42. Number 27. Number 13. Number 5…

Then shortly after Charlie Chaplin’s coffin goes missing in Switzerland, ‘Wuthering Heights’ reaches number 1, dislodging ABBA, and staying there for four weeks. It bears no resemblance to post punk (it was released on the same day as Magazine’s ‘Shot By Both Sides’), or to MOR (Brotherhood Of Man’s ‘Figaro’), or to disco (The Bee Gees’ ‘Saturday Night Fever’). But other piano-propelled hits sung by women will join this number 1, starting with Blondie’s breakthrough ‘Denis’, although this is a cover and Patti Smith’s ‘Because The Night’, which was co-written with Bruce Springsteen. Romance is back but the last time it came across the moors from beyond the grave to top the charts was 17 years ago, via John Leyton’s Joe Meek-produced ‘Johnny Remember Me’.

The headlines hyperventilate (“Wuthering Wonderful!”, “A Tonic For The Doctor’s Daughter!”), and cameras snap, including, by the end of the year, David Bailey’s, for Vogue. Kate Bush, now proud owner of a £7,500 Steinway Grand piano, the first to make tea in the studio, is the most photographed woman in Britain.

In 1978 Kate Bush seemed like an overnight sensation. But what pirouetted into public view fully formed had taken years of preparation. It had started at home, at the East Wickham Farm, a domestic academy of rich, arcane knowledge in Welling, Kent.

Music was everywhere – her GP father, Robert, playing Chopin, Schubert and Beethoven at the piano, her Irish mother, Hannah, a nurse, a dancer. Pre-school, Bush sang along to Irish and English traditional music, as she had it, dirty sea shanties and Bert Lloyd; rich narratives defying logic and taboos, full of tragedy, transformations and bawdy humour, raw poetry of fantasy and flesh.

Her older brothers were also busy exploring folk traditions. Jay was a published poet and photographer, while musician Paddy was an encyclopaedia of archaic, pan-global instrumentation. Their old 45s and prog helped shape her musical imagination and she was sophisticated beyond her years, viewing pop through a much wider lens than mere current trends. Books were everywhere too, a library’s worth. They were, Bush said, a very observant family, fascinated by what motivates people. This keen interest in psychology would surface in her work’s piercing, delicate insight. Conversation was her biggest influence: “People are full of poetry”, she once said. By the age of 11, her own poems featured in the school magazine – there were stanzas on the crucifixion, alienation, death and deathless romance, coming through “gates of glass” on ‘Call Me’, existing beneath the “pimpled surface” on ‘You’. They came with record collection references too, on Epitaph For A Rodent (Donovan) and Blind Joe Death (John Fahey).

She developed more populist tastes, with TV’s visceral impact and the discovery of her own musical heroes. Elton john’s Madman Across The Water was rarely off the turntable. She loved Bowie’s “constructions” and “insect-like beauty”, and cried at Ziggy’s farewell show. Besides Roxy Music’s “moods and atmospheres”, her ears were equally open to outré novelty (Napoleon XIV) as they were to studio-bound perfection (Steely Dan). Billie Holliday and Lotte Lenya aside, her influences were largely male, though she’d later single out Joni Mitchell and Joan Armatrading as “special”. But Bush’s musical life started as the female singer-songwriter boomed. 1971 alone had Blue, Tapestry, Carly Simon’s No Secrets and Judee Sill. In 70s Britain there were a stunning sequence of albums from Sandy Denny and the underrated Lesley Duncan.

Life inside the gates of St Joseph’s Convent Grammar School contrasted starkly with what her brother Jay referred to as her home’s “warm Anglo-Irish mish-mash”, its rigid rules and adolescent social Darwinism making her “introvert”. The collision between home and school produced a wide-eyed, world-weary tension in her work, idyllic and foreboding forces fuelling that romantic, gothic imagination. Compare shy, unassuming Cathy hiding behind her hair in the school photo with the one seen through Jay’s camera inside East Wickham; dressing up, projecting an image, rehearsals for pop’s magnetic, reluctant future star. Sedate Englishness shrouded a “wild Celtic streak”. It was, as early song ‘On Fire Inside A Snowball’ put it: “Hot inside the ice”.

Those songs emerged swiftly after her Dad showed her the middle C on the piano, and she discovered chords (something she described as “the most exciting thing”). Composing put her poetry to music, channelling the “excess of emotion” inside. What started as a “private thing between her piano and imagination”, according to brother Jay, resulted in an ever-expanding songbook, copyrighted through self-addressed mail, captured on an Akai tape recorder. Plugger, Ricky Hopper, a Cambridge friend of Jay’s, circulated the tapes. Labels rejected them as “morbid, heavy and negative”. But Pink Floyd’s David Gilmour immediately heard a “remarkable talent”. He recorded her several times, alone at the piano, and in August 1973, with Unicorn’s rhythm section at his Essex home studio. ‘Future Army Dreamers’ B-side, ‘Passing Through Air’, comes from these sessions; doe-eyed, dreamy soft rock, remarkable for the barely 15-year-old Bush.

In June 1975, Gilmour funded recordings at AIR studios. They were cut with an illustrious cast; producer/arranger Andrew Powell, Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick, and players who’d worked with David Essex, Cat Stevens and Bowie. Of the three tracks recorded, ‘Humming’, aka ‘Maybe’, was Elton-indebted (like gorgeous home demo ‘You Were The Star’). The other two, surfacing on 1978’s The Kick Inside, showcased something unique.

‘The Saxophone Song’ had evocative scene-setting (“a smoky Berlin bar”), sensual musicality (“a beautiful sax like a human, a sensuous shining man being taken over by this instrument”) and role-playing (Bush as the “surly lady” spectator). Powell was, Bush says, “incredibly tuned into my music”. His keyboards flicker “like streams of light flashing off” the sax to the narrator. Alan Skidmore, who’d played with the Brian Auger Trinity, blows the titular instrument, neatly contained ripples of free jazz, flowing from player, instrument to listener. Everything merges in music’s boundary-blurring, life-changing power.

‘The Man With The Child In His Eyes’ was cut live, the not-yet 17 year old Bush at the piano, with a 30-piece orchestra. Equal parts hazy 70s confessional, haunting Old English ballad, it gave Emerick goose bumps. Drafted in her early teens, the inspiration was, Bush says, “a man I’d been in love since I was 13… a real schoolgirl crush”. It’s a “fantasy trip” about an idealised older male who retains his child-like wonder (compare with Joni Mitchell’s man-child frustration on 1976’s ‘A Strange Boy’). Released in May 78 to showcase Bush’s song writing, after ‘Wuthering Heights’ eccentricity, it peaked at 6 in the charts.

Teenage longing is given a similarly mythical, mystical spin on early home recording, ‘Something Like A Song’, with its Wind In The Willows-style dream lover. Bush’s voice emulates the pipe-playing phantasm’s tune, soaring into pure sound. Bafflingly abandoned, its nocturnal visitations from an oddball romantic co-star foreshadowed Misty’s tryst with a snowman several decades later.

The AIR sessions secured a deal with EMI that was finalized in summer 76. Bush had left school, with ten O’ Levels, forever abandoning any regular career (veterinary, social work, psychiatry). But neither she nor label considered her “ready”. She left home, and studied movement with Bowie’s former instructor/lover, Lindsay Kemp (she’d seen Flowers at the Collegiate Theatre the previous year). She continued dance lessons with Adam Darius and Robin Kovac, co-choreographer of the ‘Wuthering Heights’ routine.

Presenting her songs through dance would avoid ‘woman at piano’ clichés. It also transformed the music itself, worked on alone at night after class. Composition, piano playing and singing all rapidly evolved during this period, accelerating into one balletic “fusion of gifts” as her Dad described it. On the unreleased ‘Rinfy The Gypsy’, dazzling ivory runs accompany a torrid suburban Rapunzel melodrama (see also the strutting swagger of ‘Pick The Rare Flower’). The voice, once deemed “unremarkable” and “foghorn-like”, has become a startling octave-skater, imitating the piano, everything dancing, moving. Behind flash there’s always raw feeling, like Billie Holliday, whose one-octave limits Bush found “so emotional and so tearing”. (Later, Tricky would see the connection.)

EMI press shot

Bush’s pre-fame piano and vocal recordings are a treasure trove of obscure gems. Their release vetoed by Bush in 1987, a Joni Mitchell-style archive campaign seems unlikely. But 2005’s Aerial dipped into this semi-secret history – ‘Atlantis’ (‘A Coral Room’), ‘Craft Of Life’ (‘Mrs Bartolozzi’) and ‘Where Are The Lionhearts?’ (‘Joanni’) are all from this period.

Throughout, real experience bleeds into imaginary innocence – stories flickering with personal “intense yearning”, as Bush herself would describe it. Songs that stare so deep into men’s eyes they become swimming pools. Songs that start like a young woman’s diary entry, then veer off in unexpected directions, delivering sharp insight on ‘Frightened Eyes’. They’re full of swoops and dips, at turns wacky (‘Stranded At The Moonbase’), and heart wrenching (‘Dali’), already possessing a searing emotional purity that’s beyond her heroes. The queer, echo-laden sound quality of ‘While Davy Dozed’ and ‘Come Closer’, adds an almost proto-hauntological texture; both songs are part lovers’ plea, part incantation. With just voice and piano, scenes and moods shift.

While unique, they also sit in a comfortably parallel zone to British female singer-songwriter arcana of the 1970s – Catherine Howe’s What A Beautiful Place, Mandy More’s But That Is Me, and Linda Lewis’ Lark. Bush’s early songs could have snuck onto 71’s The Beautiful Changes by Julie Covington, a family friend, who later covered ‘The Kick Inside’.

Between signing to EMI and recording her debut, Bush made her first forays into live performance with the KT Bush band, featuring drummer Vic King, guitarist Brian Bath, and boyfriend/bassist Del Palmer. After 20 or so pub/club gigs, EMI, no doubt eager to fill a post-Pistols void, summoned her to AIR studios. During July/August 77, The Kick Inside was made, selected by Bush/Powell from tapes containing 100 songs. Organised, professional, super-musical Powell was a perfect foil, assembling a team from Cockney Rebel (drummer Stuart Elliot, keyboardist Duncan Mackay) and Pilot (bassist David Paton, guitarist Ian Bairnson). An orchestral arranger, he’d worked with both groups and provided Al Stewart’s 1976 Year Of The Cat with strings that enhanced its plot-thickening drama. He’d produced baroque & roll too – David Courtney’s …First Day from 1975.

Too exotic, theatrical and sensuous to slip into AOR/MOR, Powell furnished The Kick Inside with sympathetic settings, bathing them in magic-hour luminosity. Much of it was recorded live, sprinkled with striking overdubs (Powel’s beer bottles, Morris Pert’s boobam, Paddy’s mandolin). It’s as deep 70s as starburst lighting, from Mackay’s funky clavinet and sparkling electric piano to ‘Strange Phenomena’, with Bush’s Twilight Zone piano and the bubbling sci-fi synths. Amid the idiosyncratic balladry there’s stylistic variety – funhouse reggae on ‘Kite’ (she described it as “a Bob Marley song”) and ‘Them Heavy People’. ‘James And The Cold Gun’, all vamping piano and savage riffage, rocks on its own terms; a tempo-shift coda, devised live by the KT Bush Band, and banshee-like backing vocals, unleashing irrepressible weirdness. Clusters of Kates festooned the album, flapping their wings on ‘Moving’ and ‘Kite’, “a cast of characters” to support the main lead vocal.

Dedicated to Lindsay Kemp, ‘Moving’ opened and closed with humpback whale-song, a light sound from a heavy creature on a song about the choreographer’s ability to set spirits dancing from awkward limbs. Filling empty vessels up with “moving liquid”, he’s the inspirational lifesaver, “crushing the lily in the soul”, as the music man does on the following ‘The Saxophone Song’.

Efflorescence runs throughout the album’s lyrical lexicon, a sense of things coming to life, growing, physically and mentally, something stirring, kicking deep inside. ‘Them Heavy People’s rolling ball comes stuffed with philosophy and movement, the two linked by the referenced Gurdjieff, the Greek-Armenian Sufi mystic. Here Bush is the wide-eyed eager pupil; by 1981 she’d be staring more quizzically at that ball on the cover to ‘Sat In Your Lap’. Bush may have adopted a ‘male’ approach, but rarely had female experience been so centre-stage. ‘Strange Phenomena’ tied in the phases of the moon with the menstrual cycle. There are period pains on ‘Kite’, pregnancy on ‘Room For The Life’ and ‘The Kick Inside’. Years before ‘Running Up That Hill’, Bush is already acting as a conduit for ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ energies (Trouser Press described the music as “tough, despite its aerial quality”).

‘Strange Phenomena’ was about the unknown forces that guide us, with its “clusters of coincidences”, the extraordinary in ordinary lives. There are chants from Tibetan Buddhism, and elsewhere, “old goose moons” from Cree mythology. But for all the Tarot card mysticism, and whiff of incense and patchouli, at the album’s core is the earthbound, joy of sex. ‘Feel It’ is cringe-free erotica and was one of three solo piano performances recorded (of the two unreleased one was a gorgeous ‘Cussi Cussi’) and was boudoir bliss miles from Joni Mitchell’s lonely “pick-up station” (‘Down To You’). ‘L’amour Looks Something Like You’ with it’s “sticky love inside” was more bittersweet but just as poetically, frankly carnal. Few songs capture rapturous romance the way ‘Oh To Be In Love’ does. The Kick Inside feels suffused with elation, basking in that long hot summer of 1976, when much of it was written.

But it ends with incest and a suicide note. The title track – inspired by folk ballad ‘Lucy Wan’ was a portal to the darker areas Bush would soon explore. Potentially lurid, gloomy material, in Bush’s hands is woven into a judgement-free eternal love-song, like the A-side’s closer, ‘Wuthering Heights’.

The artwork swapped Mankowitz pink leotard for Roxy cover star drifting away in a surreal world, a gold body-painted Kate clinging to a kite, assembled by her Dad, from painted paper and wood. To photographer Jay Myrdal’s chagrin, his portrait was superimposed onto a giant parasol-like all seeing eyeball – a nod to Jiminy Cricket with umbrella, floating past the whale in Pinocchio. The flip’s dark grainy sky, evoking those “wiley, windy moors” was shot by brother Jay, boyfriend Del Palmer illustrated the kite-flying deity; a family-run cottage industry within the world of major labels already. By the time of The Kick Inside‘s 17 February release, Bush was already regretting the ‘Oriental’ lettering. It sailed to number 3, topped the Dutch charts, found its way into Mavis Riley’s hands, and Suzie Burchill’s collection, on Coronation Street

Her pan-generational fan-base and diverse famous admirers Dusty, Bob Geldof, Steve Harley, Sparks, Auberon Waugh, indicated a broad appeal, one that stretched from K.D. Lang in Alberta, Canada, to Brett Anderson in Hayward’s Heath, Sussex.

With fame came unavoidable compromises. Her first Top Of The Pops appearance, 16 February was, for Bush, like “watching myself die”, replacing ‘Wuthering Heights’ carefully prepared backing track with Johnny Pearson’s orchestra. Despite regular, lively TV performances, from Saturday Night At The Mill to the Peter Cook-hosted Revolver, she was better suited to the burgeoning medium of video. ‘Wuthering Heights’ came with two, one in a red dress, Salisbury Plains standing in for the Yorkshire Moors. The other, directed by Keith ‘Keef’ Macmillan, at Wandsworth’s Ewart Studios, saw her twirling, waving, and cart-wheeling, in a white King’s Road night dress, kohl eyes expanding, leaving ghostly trails created by video effects.

For Bush, sudden, unexpected success “blew my routine apart,” wrenching her from the creative process. Her promotional itinerary was frenzied, like going “around the world in 80 days”, taking in Germany, Italy, two US trips, and performing at Tokyo’s 7th Music festival (‘Moving’ reached number 1 there).

Her second album that year, Lionheart, featured just three new songs, ‘Symphony In Blue’, ‘Full House’ and ‘Coffee Homeground’. The rest came from her pre-1978 stockpile. (‘Wow’ had already been considered for The Kick Inside.) Recording took place at Superbear Studios, in the mountain village of Berre Les Alpes near Nice. Powell produced and arranged again, this time Bush assisted. She sought more control, wanting The KT Bush band and brother Paddy to feature heavily. With King now replaced by drummer Charlie Morgan, they’d demoed the tracks in East Wickham farm’s grain store, where she’d played a mice-ravaged Victor Mustel harmonium as a kid, and where she would later build her own studio. Powell used the KT Bush band on ‘Wow’ and ‘Kashka From Baghdad’ but felt they lacked studio experience. His trusty Kick Inside team completed the album.

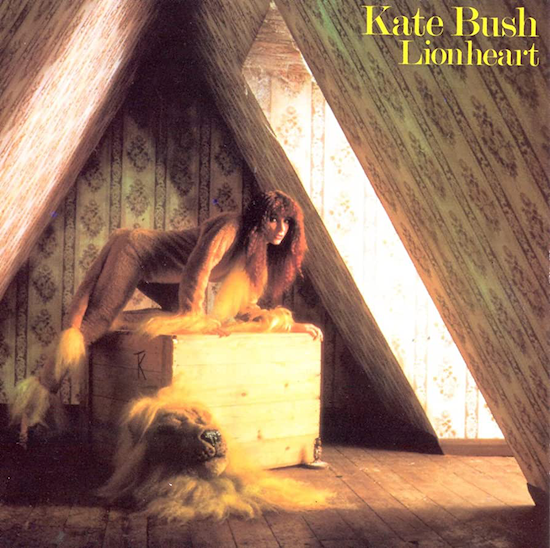

It’s now considered bottom-shelf Bush, a rushed compromise disliked by its creator. In 1978 though, Bush saw Lionheart as being more “adventurous” than its predecessor on every level. Wanting to distance herself from “soft, romantic, airy-fairy vibes”, seeking more “guts”, a “heavier sound”, telling journalists she read more Kurt Vonnegut than Brontë. The title exuded strength: a less clichéd word for ‘hero’, the work of a sturdy Leo. It also shared its name with a 1968 Children’s Film Foundation movie with a very Bush-like plot, involving a boy protecting a fugitive circus lion. The cover evoked East Wickham wonderland, shot by Mankowitz, conceived by Jay; Bush in lion gear crawling across a dressing up box in an attic. Inside, the music had more costume changes than Mr Benn.

Lionheart is darker and deeper, charged with what Melody Maker’s Harry Doherty called “a more vigorous sense of drama” as Bush “lets her subconscious run amok in the studio”. Character-hopping, story-telling, psychologically astute, The Dreaming‘s auteur is already lurking here, even though the Fairlight and sharper sonic edge aren’t. But the collision between Powell’s gloss and Bush’s increasingly macabre, provocative imagination creates a cosy, deep unease. There’s an almost televisual creepiness to the music’s symphonic sweep (‘Kashka From Baghdad’ was inspired by a 70’s US detective show). A year before Tales Of The Unexpected was televised, you can almost see the shimmying silhouette and flickering flames through Lionheart’s sound.

It’s riddled with paranoia. ‘Coffee Homeground’, inspired by a US cabbie, explores its “humorous side”, ditching the demo’s guitars for a Brechtian orchestral romp, Bush thickening the Weimar cabaret with a German accent. The plot, a guest besieged by a poisoning host seems ripped from Roald Dahl’s 1959 The Landlady. But the mock-menace suggests an imagination working overtime. As does ‘Full House’, an early example of Bush’s interest in “distorted” mental states, her murder mystery piano tilting the rock axis.

Uncanny drama, nearly running “your old self” over on a night drive, carries rigorous self-analysis, the intellect wrestling control back from overpowering emotions and the internal chatter of those nagging backing vocals. Both off-kilter songs sprang from a Bush who’d been exposed to the media’s harsh, skewed glare. ‘Don’t Push Your Foot On The Heartbrake’ also used car-driving as a trope for managing emotional vicissitudes. Described by Bush, in the KBC newsletter of Summer 1979, as a “Patti Smith song”, it dragged the quiet/loud dynamics of Horses’ ‘Break It Up’ onto Broadway’, echoing David Bowie’s theatrical twists on US rock.

‘Hammer Horror’ took paranoia into gothic territory, bringing Lionheart to a gong-crashing finale. Bush spoke of feeling spooked in the darkened vocal booth “as if someone else was there”, studio-fright she transfers to the guilt-ridden actor here, plagued by the ghost of the friend he’s replaced in the leading role. She was offered various horror movie roles at the time, “playing opposite Dracula-types”. But inspiration came, not via Bray Studios, but from 1957’s The Man With A Thousand Faces; James Cagney playing Lon Chaney, playing the Hunchback of Notre Dame, as revealed in the KBC newsletter of November 1979. A “nail-biter” for NME’s Tony Parsons, Hammer Horror comes with comic puns from its humour-loving author.

Lionheart’s first single, released just before Halloween, 27 October, ‘Hammer Horror’ slumped in at 44, faring better in Ireland (10) and Australia (17). A great ‘lost’ 45, it’s a multi-tiered melodrama, compressing eerie verses, reggae-bridges and a chandelier-shaking chorus into 4’40”. Cobwebbed grandeur, from piano and harmonium, combines with full throttle terror – shuddering strings, howling guitar. Written back in 1977, pre-fame apprehension meets vaulting ambition, anticipating The Dreaming, fretting ‘Is this the right thing to do?’ The vocals also flash forward to 1982; method actor immersion from multiple personalities, wordlessly sweet one minute, lunging towards the grotesque as she spews out the title, the next.

The frightening fun was visualised in the Keef-directed clip. A Salome-like dancing Bush was pursued by a masked executioner – dance partner Anthony van Laast (co-choreographer of the 1979 tour). In the final frame he throttles Bush, thumbing the nose to some of 1978’s creepier press coverage; ghoulish predictions and feigned concern, about “the music biz tightening its grip around her swan-like neck” (Record Mirror) and about the “strange birds gathering in trees” waiting to prey on the “fragile” Bush (Sunday Times).

EMI press shot

‘Wow’, a no.14 hit in 1979, was also about actors and “the magic of showbiz”. An orchestra warms up, synth arpeggios glow, fluorescent lights scanning the theatre, build-up for the chorus’ pure populist spectacle. Bush’s siren-like voice takes flight, Warhol superlatives swinging from a trapeze (the moment Faith Brown, parodying it, was hoisted into the air). On a song about the performer’s toil of grace, the vocal took countless, technically perfect takes, until she found the elusive alchemy she was pursuing. Bush spent much of 1978 decrying stardom’s “ego and glamour” to the likes of Harry Doherty in Record Mirror and to Tim Lott from the same publication, the “Oh darling! Where’s my champagne?” sycophancy, and the “disgusting” parties. In the verses, rat race reality hovers in the smoke and mirrors; fake praise, thwarted ambition. The only role left for the aspiring “movie queen… hitting the Vaseline” is “the fool”; sharp insight in an era when the only options for him were the closet or sit-com clown.

Meanwhile, the gay lovers in ‘Kashka From Baghdad’ blissfully dwell in their private world, away from prying eyes and judgement, where “they know the way to be happy”. Another Bush story where love exists beyond all social limits, against all odds, its light shining deep within, brighter here than the moon. To make the gay angle overt, she cast herself as the voyeur, longingly watching their “tall, slim” shadows. It sensuously luxuriates in something still considered taboo, the “strong Islamic flavour” summoned by ‘Paddy’s zither-like strumento de porco, adding another layer of oblivious subversion. The mysterious aura has a delicate irony, unsettled by the outside world’s mores, not the happy couple indoors.

She smuggled it onto kids’ show Ask Aspel, the same year the BBC refused to play the no. 16 hit, ‘Glad To Be Gay’. She’d sung about “beautiful” heartbroken queen Eddie on the older, unreleased ‘The Gay Farewell’. Reviewing her concert in 1979, Sounds observed a strong gay presence, euphemistically referred to as “nice chaps… the Judy Garland/Bette Midler axis”. She expressed relief that the national media didn’t scan those lyric sheets, not “wanting to upset anyone who didn’t understand”. But her fearless sensuality forced her to explore areas still considered forbidden for pop.

It was also instinctively inclusive. Kashka followed ‘In The Warm Room’, a heterosexual male bedroom fantasy, a piano ballad full of unresolved jazzy spaces, channelling Holliday, wrapping her vocals around “marshmallows” like a punch-drunk torch singer. It’s pure erotic reverie unlike opener ‘Symphony In Blue’ where sex is just part of the pantheistic philosophising. Here an auto-erotic expression of female pleasure seamlessly flows into ruminations on God, Death, and Music (Prince released ‘For You’ that April). It’s all wrapped in blue, not just the colour of sadness, but also Wilhelm Reich’s orgone energy (she already owned his son Peter’s A Book Of Dreams). Introspection gives way to a broader focus, music being Bush’s higher purpose, seeing herself “on the piano as a melody” – another song where player and instrument bleed into one. Musically it shifts gears, Satie-like dreaminess, sweeping urgency, a circling carousel-like refrain; all part of the symphonic “oneness of all” (see The Beatles’ ‘Within You Without You’).

Grown-up stuff for a record featuring two appearances from Peter Pan “whose tricks keep us on our toes”. On ‘In Search Of Peter Pan’, he’s an escape route for a child disenchanted by the adult world. It rises rocket-like, from school-gate sadness into Neverland-bound space, airborne like so many songs about eternal children, from Scott Walker’s ‘Plastic Palace People’ to Bowie’s ‘Life On Mars?’ to Vigrass and Osborne’s ‘Ballerina’. Here, deep melancholy swells into haunting baroque, choirs of celestial Kates invoking Walt Disney (Peter Pan & Pinocchio’s ‘When You Wish Upon A Star’). Wipe away the fairy dust and there are gimlet-eyed observations on how spirit-crushing adults manipulate children, (granny is putting the “sad old man” in the child’s eyes).

On ‘Oh England My Lionheart’, JM Barrie’s hero steals the kids in Kensington park – just one of many poetic visions of a dying soldier’s Albion, part real, part magical Powell/Pressburger montage. Play the Stones’ ‘Lady Jane’ next to this modern madrigal, featuring Richard Harvey’s recorder and Francis Monkman’s harpsichord, and Jagger sounds stilted, contrived. Its closer to Rupert Brook’s ‘The Soldier’, a WWI poem with “hearts in peace, under an English heaven”. Boldly envisioned as a contemporary Jerusalem, it would later make Bush cringe, at the time it was her proudest achievement. 1980’s ‘Army Dreamers’ was less misty-eyed (grandfather Joe Bush served time in Wormwood Scrubs as a conscientious objector). But there’s no chest-beating jingoism to the romantic nostalgia here. It vividly conjures the bucolic England that united left-wing radicals (William Blake and William Morris) with traditional conservatives, the one Thatcher’s free-market would soon bulldoze its way through.

Released on 13 November, launched with an EMI-thrown party at Dutch medieval Ammersoyen Castle, Lionheart peaked at number 6. One admirer was Tony Visconti, who sent Bush fan mail while making Bowie’s Lodger. Like that 1979 album (and Peter Gabriel’s Scratch), Lionheart is another misunderstood masterpiece, judged more by its context within a discography rather than on its own merits.

Bush scooped many awards in 1978, two from Melody Maker readers, a prestigious Dutch Edison for ‘Wuthering Heights’, but for certain quarters of the music press, it was all a bit too much. Ian Penman, reviewing Lionheart in the NME, lumped her in with MOR chanteuses like Barbara Dickson and Lynsey De Paul. Reviewing her concert the following year Charles Shaar Murray, also for the NME, dismissed her as an elitist throwback to Mainman-era Bowie, telling BBC R4, in 2014, that at the time he considered Patti Smith a “cutting edge female artist”, as if there was a prototype. It was a view rooted in punk past, not pop future, with Bush’s theatrics foreshadowing spectacles from Madonna and Pet Shop Boys. By 1979 old and new waves crashed in the same ocean anyway: Patti Smith resembling Stevie Nicks on ‘Frederick’, Nicks spiralling poetically like Smith on Fleetwood Mac’s unedited ‘Sara’. ‘Wuthering Heights’ and ‘Heart of Glass’ were absent from the NME‘s end of 1978 list (just as ‘I Feel Love’ had been in 1977).

Punk orthodoxy was happy to celebrate Siouxsie, Smith, Poly Styrene and Pauline Murray as the trailblazers they were, but women who fell outside the paradigm could be subject to punk’s dreary, reactionary, even misogynist side (see The Rotters’ ‘Sit On My Face Stevie Nicks’). While Shaar-Murray saw Bush’s music as “too dainty, too prog”; Lee ‘Scratch’ Perry called her “the only angel left” in Uncut, June 2010, while Tricky, writing for Mojo, said “I don’t believe in God, but if I did, her music would be my bible.”

Perhaps those naysaying scribes were as imperceptive as Lockwood, Brontë’s pompous narrator in Wuthering Heights, who couldn’t imagine that Heathcliff and Cathy’s spirits still roam the moors. It may have been a quaint old book on the English GCE syllabus that year, but Wuthering Heights tore through Victorian society, celebrating a union so outside its constraints, it transcended life itself. “It ought not to exist,” wrote Angela Carter on its incendiary, transgressive passion.

The same could be said of Bush who was often traduced as “nice” or “polite”, and the strange phenomena of her 1978. She possessed a deep grasp of passion herself. Catholicism lingered deep inside her. Besides music and English, she had excelled in Latin at school, passion’s native tongue – where the sacred and profane mingle, where suffering and ecstasy co-exist, where good sex is enlightenment, not guilty pleasure.

Scan those 1978 lyric sheets and you find a world at odds with 1970s Britain. A place epitomised by No Sex Please We’re British (whose film adaptation hit screens in 1979); caught between tabloid smut and bourgeois repression. Indulging in upmarket softcore like 1978’s The Stud, but rarely passion.

Punk/postpunk was itself close to being an erotic void – Lydon’s two minutes of squelching, Gang Of Four’s anti-romance/body anxiety, Magazine “drugging and fucking you on the Perma-frost” a few months after Bush invited listeners into the “warm room”. Even The Buzzcocks’ ‘Orgasm Addict’ was a cartoon Priapus.

She praised punk; the Pistol’s originality, the galvanising effect it had on its frustrated audience. But in 1978, Kate Bush was her own one-woman revolution – a gentler one, already stepping out into a sensual world, where all human desire co-exists like it does on Lionheart. If she didn’t wish to offend, she nevertheless posed a challenge, wanting to “intrude”, “to throw listeners against the wall”, “to really lay it on you”.

She hurtled forwards into art-pop, leaving behind her all those early songs, too many left unrecorded. Like Shaar-Murray, who would later praise her “mature” artistry, she became dismissive of her early works. But she’s at her least progressive when second-guessing herself. ‘Wuthering Heights [New Vocal Version]’ from 1986 had none of the original’s freakish beauty and 2011’s Director’s Cut is, to date, perhaps her only non-essential album. Never For Ever, The Dreaming, Hounds of Love, Aerial may be classics from a master, but the genius of youth on The Kick Inside and Lionheart cannot be dismissed. Both come from a curious, passionate young mind, in her words “idealistic, positive, driven”. Both represent what Simon Frith called “the triumph of the romantic will”, both show what Camille Paglia called Bush’s “poet’s instinct for the archaic and universal”.