The problematic period of the final years of the Soviet Union’s dissolution and of the establishment of a new state in the early 90s is mainly thought of as a time of crisis, but at the same time when new freedoms of expression met established avant garde tradition, creativity in the music scene blossomed, something that had previously been impossible.

In Ukraine, next to Kyiv in terms of creativity was Kharkiv, whose highly active and diverse music scene began to flourish at the beginning of the 90s, although this was often undocumented, as it was not easy in relative terms. (Music was recorded ‘by request’ in recording kiosks and similar ‘studios’ of varying degrees of legality and equipment quality. Beforehand rock had been seen as officially unacceptable in the city; judged revolutionary, Western, and standing in opposition to the Communist system.

This is not to say that such music did not emerge however. The creators of rock music operated in a completely underground manner in the late 1980s and early 1990s. They drew inspiration from punk and referred to avant garde, dadaism, and various forms of experimental music. Among the essential bands was Igra, which soon transformed into the highly original Tovarish; the primitive noise rock creating Chichka Drichka and Kazma-Kazma, the latter of which included an extended wind section, combining orchestral arrangements and Medieval melodies with dark humour and an out rock vibe.

Most of these bands had a direct relation to the Novaya Scena, which was then busy promoting noncommercial and avant garde music. Festivals organised under the banner included concerts in different genres, ranging from post punk to contemporary academic music. Its director Serhii Myasoyedov worked on engaging and original Ukrainian bands in the context of European independent music.

The Novaya Scena phenomenon quickly spread to other cities and became a term by which artists were searched for in the early 1990s. A significant achievement in the early 90s was several independent German labels issuing Novaya Scena compilations. New Scene: Underground From Ukraine! 14 Bands From Kyiv & Kharkiv and Ukrainischer Underground capture a fertile period between 1989 and 1991, featuring aggressive and uncompromising music, close to the New York No Wave sound. Thanks to these releases some English-speaking listeners learned the phrase Novaya Scena and it became a generic term for Ukrainian independent music of the 90s.

After three big festivals of the same name held in 1988, 1990, and 1992, with the latter also taking place in Kyiv and Donetsk, three Cult of Modern festivals we organized during 1994-1996 period, combining music with visual and performance art – together with phenomena such as the Lviv Alternative festival, Polish’ Koka Records, and the Quasi Pop Records label releases from the beginning of the 2000s reveal a broader perspective of the Ukrainian underground. After the last big festival, ‘Східний експрес’ [East Express], held in 1997, Novaya Scena came to an end.

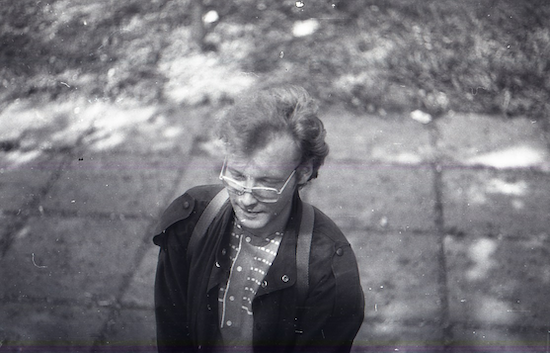

One of the artists who was constantly active in this network of underground bands was Oleksandr Yurchenko, a Ukrainian musician and illustrator, who functioned between Kharkiv and Kyiv and, from the 1990s and co-founded bands such as Yarn, Merta Zara, Elektryky, Kvitchala v Serpni, Radiodello, Suphina Dentata, Suphina’s Little Beasts and Blemish (many of whom have been re-released by Bloomed In September Tapes in recent years). His works include cheerful indie rock and multi-layered avant garde experiments. His genres include synth pop, industrial, post rock, ambient, funk, dark folk, and improvisational modal music using synthesizers, electric viola, and homemade instruments. He was one of the most important figures from this scene, yet the most mysterious.

Yurchenko has created music that is difficult to pigeonhole, somewhere at the intersection between folk, industrial, and drone music. In Elektryky, who recorded two albums before transforming into Yarn (which would combine medieval aesthetics, folk motifs, and some contemporary trends in alternative music), Yurchenko used the dulcimer for the first time, played prepared cymbals and an electro viola of his production. On the band’s second album, he used a plucked string instrument made from the remains of a balcony frame, according to legend. It was a board with four strings and a guitar pickup. Yurchenko had to rearrange the instrument for each song. He was an outstanding melodist, too, adding minimalist themes on the guitar or keyboards (you can listen to the recording of Yarn here).

In 1994 Yurchenko and his wife Svitlana Neznal created the Merta Zara project, which produced only one, home-recorded, session during their time. He played the electric viola, while she sang and played mandolin. The only result of their work was the track ‘Ubrannya’, released on one of the compilations mentioned above. However, the world remembered Yurchenko a few years ago with the reissue (first by Delta Shock, then Glasgow’s Night School) of the neo-folk recording Znayesh Yak? Rozkazhy made with Svetlana Nianio and initially released in 1996, on which Yurchenko’s combined hammered dulcimer with Casio keyboard lines.

Although Delta Shock and Bloomed In September Tapes have started releasing music from his archive in recent years, the Shukai label, founded by Dmytro Nikolaienko along with Dmytro Prutkin and Sasha Tsapenko, have collected a vast body of his work on Recordings Vol. 1, 1991-2001.

The album’s culmination is Yurchenko’s main work, ‘Count to 100. Symphony #1′, documented in August 1994. A single 25-minute piece of layered bowed drones which create a quiet drama which unfolds gradually with some lo-fi distortion weighting the piece, creating a dimension of transience, perhaps of irretrievable loss, which at one point succumbs to plummet into ambient depths. This track showcases the stringed instrument of his own invention. He processed the sound through a reverb chamber live, followed with some manipulation of the tape loops. The improvised recording session was held at home – he turned the instrument into a unique tone generator using guitar delay effects, loops, and an Oreadna portable cassette recorder. It was one of the last hurrahs for an acoustic-based process before Yurchenko turned to mainly electronic instrumentation in the late 90s when he recorded albums with Svitlana Nianio.

At the beginning of the 2000s, Yurchenko decided to edit the original version of the symphony; attempting to restore the recording using production effects. At the end of the work on this project, he left this version in his archives and decided to publish the original recording in the late 2010s. Now, thanks to Shukai, a Muscut sublabel, we can listen to the edited version from 2001.

Another aspect of Yurchenko’s sonic signature can be enjoyed here via his elaborate and weird arrangements in the spirit of DIY. ‘Intro’ sounds like an endlessly-looped stream with delicate fragments of guitar sound twisted into a deep pattern. ‘Merta Zara’ takes its name from a project by Yurchenko and his wife. As Yurchenko had a deep knowledge and appreciation of music from Central Asia, it is understandable that such tracks stand in a folkish tradition but combine the acoustic sound of his invented mandolin with electric cello. Yurchenko draws attention to the sonic textures and timbres of the instrument – traditional music and his melodic skills are intertwined here.

Solo recordings of Oleksandr Yurchenko, made during the last decade of the 20th century, draw attention to how he experimented with sound and sought out new paths towards creative freedom. His drone symphony can be compared with the works of such avant-garde composers as Glenn Branca or La Monte Young. Listening to them now, retrospectively, I would also add a comparison to the music of Swans and Godspeed You! Black Emperor. Yurchenko wasn’t able to have his music released officially in the 90s and made only a few copies of these tracks for his friends. He was a forgotten figure for many years due to the lack of documented, officially released recordings. In the 2010s, he was asked for an interview but refused, already suffering from a severe illness. In April 2020, he died, leaving behind a great, if mainly unknown, musical legacy.

Like Valentina Goncharova, Yurchenko searched for sound in how he played and by constructing unconventional hand-made instruments. Shukai once again unearths a forgotten (also for political reasons at the time) gem of the Ukrainian underground to a broader audience and broadens our perspective on the country’s experimental scene in the 1990s.