Le Peintre II (Le Peintre et son modèle II) [Der Maler II (Maler und Modell II)], 1923. Huile sur toile, 85,5 × 130,5 cm

Saint-Louis, Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest Morton D. May © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka, 2023, VEGAP, Madrid

Warped and grooved, the italic initials ‘OK’ sit uncomfortably in the corner of every painting by Oskar Kokoschka. Like a scar, his signature is scratched deep into the surface of his works – his defiant ‘I was here’ to the history of art.

Kokoschka tirelessly promoted himself as the foremost portrait artist of the 20th century. Inspired by the Wagnerian idea of Gesamtkunstwerk – the Total Work of Art – he sought complete control over his own image. And Dieter Buchhart, Anna Karina Hofbauer, and Fanny Schulmann, curators of A Rebel From Vienna, have bought and resold his story, in their similarly European exhibition.

“Rigidly individualistic,” (according to his biographer, Rüdiger Görner) Kokoschka refused to identify with other movements. With his first patron, Adolf Loos, he turned his back on the Vienna Secession and its Arts & Crafts off-shoot, the Wiener Werkstätte in 1910, to pursue his own multidisciplinary path. He snubbed the Parisian art market – perhaps a means of self-preservation from his little commercial success – and in the UK, distanced himself from artists’ groups in St. Ives and north-west London, where he lived for a time in the 30s and 40s. We hardly see how these places and people – from Fred Uhlman and Diana Croft, to fellow émigré artist Marie-Louise von Motesiczky – influenced his life and works. Only how he impacted them.

Though he often portrayed his cultural milieu – writers, musicians, and performers – Kokoschka scarcely depicted visual artists, reluctant to promote the competition. In Rebel From Vienna, we see a portrait of Carl Moll, who co-founded the Secession with Gustav Klimt, but here as a collector, a bourgeois businessman – and not an artist.

One of many contradictions: the artist was happy to claim his influence by more classical, traditional artists, like Rembrandt, Titian, and Raphael. At best a moderate, but most likely more conservative than his peers, his traditional tastes ensure his late works are somewhat comfortable, nostalgic, if not plain fence-sitters. (Whilst publicly opposed to abstract art, it clearly influenced these figures’ blurred forms.)

By the time Murderer, Hope of Women (1909), his controversial play, was published by his Berlin-based patron Herwarth Walden in Der Sturm, he had already started, as the gallery wall texts put it, to “stage his own artistic development”. In the same year, he shaved his head to resemble a prison convict, a performance created for his public image.

Oskar Kokoschka, Alligator snapping turtles (Riesenschildkröten), 1927 Oil on canvas. 90,4 x 118,1 cm Kunstmuseum Den Haag, The Hague, The Netherlands © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka, 2023, VEGAP, Madrid

“The human is always at the heart of what I do,” he once proclaimed, and Rebel From Vienna is similarly anchored in his own figuration. His self-portrait from 1917 leads the exhibition; he points to the wound in his side, a man bound to suffer, like Christ.

Others are portrayed with less flattery. He never quite gets to the grotesque of the Neue Sachlichkeit (‘New Objectivity’) artists in Germany, but pokes fun at the connected bourgeois culture of Vienna. In reality, his interest in exposing society’s ills manifested as the same sort of voyeurism over the sick, and women, as recently addressed by the likes of academic Gemma Blackshaw. So whilst publicly proclaiming to see through pretence and privilege, it’s impossible not to see how he profited from his novelty. Nor how his portraits of other people, and even double-portraits on relationships, are really more self-portraits of the artist.

From interwar Prague, Kokoschka started to construct his own myth as an anti-Nazi, anti-fascist pacifist. 600 of his works would be seized by Nazis from German museums, nine of which were exhibited in the infamous Entartete Kunst exhibition (1937). Some went missing, and many were sold to private collections, like the infamous Die Windsbraut (‘The Bride of the Wind’).

Instead, we see archived articles by the Nazis – carefully collected by Kokoschka – which serve as evidence of his targeting and resistance; his defiant Habsburg jaw in Self-Portrait of a Degenerate Artist (1937) is the closest we get to seeing him as part of Austria in this time.

Glossed over is the extent to which Kokoschka actually collaborated with former Nazis after World War II to further his own career. In 1953, he accepted money from Friedrich Weld, an Austrian gallery worker who had worked for Hermann Göring in Paris, to establish his School of Visions in Salzburg. This decision was justified in the name of post-war reconciliation. But by this time, he was already being internationally represented by the Welds Gallery, in Salzburg, Austria.

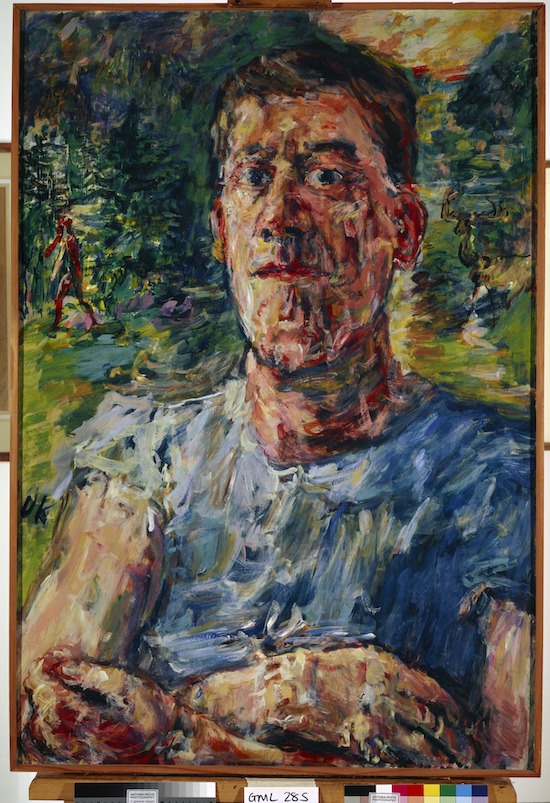

Self-Portrait of a "Degenerate Artist” / Autoportrait en « artiste dégénéré » / Autorretrato de un artista degenerado (Selbstbildnis eines “Entarteten Künstlers”), 1937 Oil on canvas 110 x 85 cm National Galleries of Scotland, On loan from a private collection © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka, 2023, VEGAP, Madrid

After World War II, Kokoschka ramped up his own propaganda machine, from the safety of his lakeside home in Switzerland. Here, he performed the European artist, positioning himself close to political power with portraits (and photo opportunities) of Theodor Körner, the first president of Austria elected by universal suffrage, and Konrad Adenauer, the first chancellor of the Federal Republic of Germany in 1966. In a grainy documentary, Kokoschka awkwardly positions himself and Adenauer in front of the camera, ensuring it captures their stilted embrace and gripped whisky glasses.

Sadly, Rebel From Vienna neither shows these political portraits, nor acknowledges this long tradition in Kokoschka’s practice. By the post-war period, he had already depicted the former President of Czechoslovakia Tomáš Masaryk, Ivan Maisky, the Soviet ambassador in London, and even Mahatma Gandhi – in perhaps the Indian politician’s first Western portrait.

From his School of Visions, to donations to the well-publicised Oskar Kokoschka Fund of War Orphans, he sought to educate people of his life as he saw fit. Rebel From Vienna’s wall text admits that My Life, Kokoschka’s 1974 autobiography, was more a work of creative fiction; “an exercise in glorification” which reflects the editorial control he practiced over his estate during his life.

Indeed, we should never underestimate the subtle power of a well-written caption, and Rebel From Vienna does not disappoint. Whilst Kokoschka scarcely spoke about the women in his life, except as romantic interests, here Alma Mahler is detailed as a composer, neither a muse nor lover.

Rather than dwell on the Doll – the focus of most previous documentaries on the artist, and a stage to perform his avant-garde credentials – the exhibition does better, implying Mahler’s influence on his life and practice. We see how she encouraged him to take inspiration from modern media like films, including The Coming of Columbus (1912), and how their travels to Italy helped him ‘find himself’ as a colourist.

(Still, Nell Walden’s portrait and patronage is nowhere near Herwarth’s, her husband. And Olda Palkovskà, a lawyer and the initiator of most of his career moves is exclusively referred to as his wife.)

Anschluss – Alice au pays des merveilles / Anschluss. Alicia en el país de las maravillas (Anschluss – Alice im Wunderland), 1942 Oil on canvas 63,5 × 73,6 cm Wiener Städtische Versicherung AG – Vienna Insurance Group, en prêt permanent au Leopold Museum, Vienne © Fondation Oskar Kokoschka, 2023, VEGAP, Madrid

Unlike his contemporaries Klimt and Egon Schiele, Kokoschka’s artworks did challenge binary depictions of womanhood. But his works will be remembered for their contradictions, rather than their originality. His exaggerated figures borrow as much from traditional Italian Mannerism as Vincent van Gogh’s impastos, the forbears of German Expressionism like Käthe Kollwitz, and other forms – like Japanese art – which here, don’t get a look in.

For Görner, the artist would always be difficult to popularise due to his complex paintings; only the Doll, as a story of failed romance, would break into the mainstream understanding of the artist. In this exhibition, which draws heavily from the Oskar Kokoschka Zentrum in Vienna, we come full circle, to see him as part of the same Viennese art establishment that he first publicly rejected – but, perhaps privately, always wanted to be recognised by.

A Rebel From Vienna is so worth spending hours rifling through. It asks whether we can ever engage with an artist like Oskar Kokoschka more objectively, on our terms, rather than his – and who gets and who reproduces that power to tell their own history.

Oskar Kokoschka: A Rebel From Vienna is at the Guggenheim Bilbao until 3 September 2023