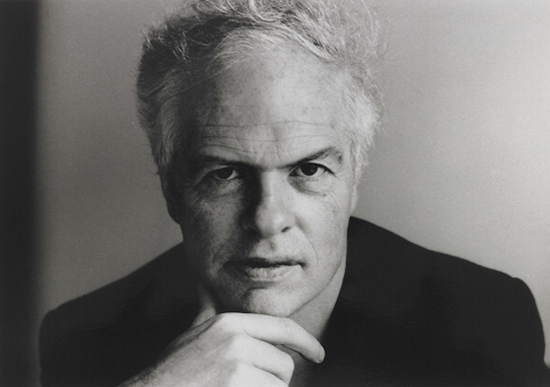

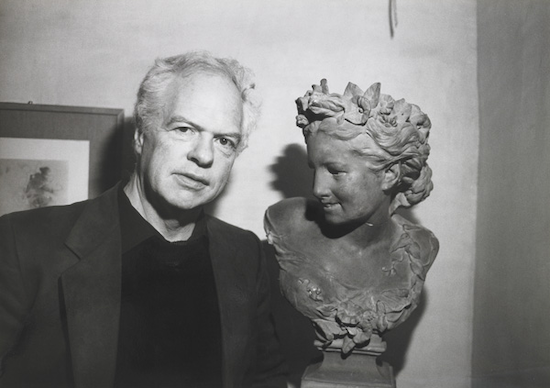

Portraits courtesy of DMThomasOnline.net

“Is it surprising that I’m terrified of art? Not that my book is a murderer, but I sense some devil having fun.”

DM Thomas – Memories and Hallucinations

I, like most, discovered the Cornish writer DM Thomas through his novel The White Hotel. I had just moved from Glasgow to Levenshulme, Manchester, and had heard through a friend about a venue of the same name that wasn’t a hotel at all, but rather a repurposed warehouse on the edge of Salford, in the sinister shadow of Strangeways Prison. “Why is it called The White Hotel then?” I asked, and they told me, and then I read the book, and from then on I was never quite sure what a novel was or what its limits were, but I knew that the form was more expansive than I’d ever thought possible.

Donald Michael Thomas was born in Redruth, Cornwall in 1935, and he died last week of undisclosed causes and with considerably little fuss. Despite being a bestselling author, famously set to tie for the Booker Prize with Salman Rushdie until he didn’t, there has been little reported about his death save for a handful of articles, most of which are paywalled. Yet the effect that his writing has on its readers is, by all accounts, profound.

It is evident that Thomas was obsessive. Or at the very least his writing was obsessive, and it was obsessed among other things with sex, death, Freud, the Holocaust, Cornwall, and Judaism, in no particular order. Allegedly described by an American journalist as ‘the world’s biggest pervert’, Thomas could turn sex scenes into genocides and deaths into ecstatic religious experiences. In his memoir, Memories And Hallucinations, Thomas tells of a woman who once informed him that his erotic poem in The White Hotel invariably made her orgasm, and then of another who claimed that it made her sick. He recounts a French journalist who tells him: “Your book is liked by les femmes, les foux et les juifs!” to which, years later, he responded in the Guardian: “Of course not all madmen, and certainly not all women and Jews; but enough to gain a great number of readers.”

His sexual obsession was evident in his personal life through his countless illicit affairs, and in his poetry and fiction it took the form of a relentless eroticism that was invariably present, indifferent to whether he was writing novels about Armenia or poems about the tin-mining industry in Cornwall.

“I am a skilled opener of mines. Then

A tiny tremor as of acute fatigue

And the total infalling collapse. Something lay still, or moaned, lay still.”

DM Thomas – ‘The Shaft’

As a result, his popularity with les femmes was inconsistent. Many women perceived his portrayal of female sexuality as distasteful to say the least. At readings, he recalls in his memoirs, women would frequently stand up to proclaim that his depictions of female sexuality were false, and then others would stand up to assert that they were true. He writes: “Since I wasn’t attempting to describe all women’s sexuality but only one woman’s, I took heart from the positive female responses.”

Thomas only began writing novels at the age of 44. Until then he was a teacher, a translator, and a poet, publishing poetry collections in the hundreds not for monetary gain (there wasn’t any to gain) but simply for the satisfaction of holding the pamphlets. As he taught full time his writing was confined to the holidays and to weekends, which were spent scrawling over a small table in his and his first wife Maureen’s bedroom. These stolen hours of bedroom writing resulted in an unfortunate misunderstanding between two friends of his wife, which he later recounted:

“Have you met Maureen Thomas? . . . She’s very nice. Her husband’s a poet.”

“My God! Really?”

“Yes. He sits up in their bedroom.”

“How awful for her!”

The friend had misheard, and understood that Thomas was a ‘pervert’. And yet despite this evidently being a misunderstanding, Thomas’ legacy as a pervert is better known than much of his poetry. It is a legacy that he has not been known to shy away from — he was a self-professed “poet/pervert, used to selling verse collections in the hundreds of copies.”

And nowhere is his perversion more masterful than in The White Hotel. The poem within Thomas’ novel is as pornographic as it is violent: fires, floods, avalanches break out and hundreds die while the heroine – Lisa – and her lover – Freud’s son – fuck outrageously. A Lutheran Pastor witnesses a breast flying through the sky. A whole host of characters, the majority soon due to be killed off grotesquely, queue to suck milk from Lisa’s breast. Thomas perverted death with eroticism, perverted religion by embroiling it in obscenity, perverted even perversion by granting it a childlike innocence, and all this in a single poem.

Still, Thomas’ perversions are even further reaching than the content of his writing. He had a way of playing with time, or otherwise blatantly disregarding it, that perverted the novel form itself. His novel Ararat, for example, is simply not interested in the laws of time or in any linear form of narrative. Instead each micro-narrative of the novel reveals itself from within the other, and is taken apart by Thomas like a set of matryoshka dolls. Thomas himself puts this down to his own disaffection with “the typical English novel”. He tells in his memoir of his lack of patience for having to describe a character’s movement from location to location, or having to differentiate between speakers during dialogue. Much like how he deals with the inconvenient issue of time, Thomas solves this problem for the most part by simply omitting such features from his writing.

He perverts time to different ends in The White Hotel. With this novel, Thomas took our generally accepted understanding of the past as a root of trauma and asked — is it possible that our futures can cause us trauma too? It’s a question that’s eerily relevant now. But then Thomas was a firm believer in what he referred to as the ‘Ley Lines of coincidence’, and was accustomed to the serendipity surrounding The White Hotel. His surrealistic visions and depictions of the future juxtaposed the weird (characterised by a sense of un-belonging) with the wyrd (premonitions of the future, or fate). The flying breast provides the perfect image of the two, at once breathtakingly surreal, and a premonition of the injuries that the heroine will suffer in due course.

In this way as well as others, Thomas leaves his legacy. Take The White Hotel venue in Salford. It too has its dealings with the weird and the futuristic, envisioning utopias and futures beyond the traumatic apocalypses that we are so often encouraged to accept as inevitable. The venue, too, creates space for perversion, or what once was considered perverse, or what one day will be. Like Thomas, it encourages us to consider why something is perverted in the first place, or why we insist on perceiving perversion as an inherently negative trait. Like in Thomas’ novels, perversion becomes poetic.

Thomas’ fascination with his home of Cornwall is a lesser-known fixation of much of his poetry and earlier novels. In 1973 he published the long-form poem ‘The Shaft’ — a twisting, digging poem about the often perilous tin-mining industry in Cornwall. Its prologue is concise:

“A few tin-mines in Cornwall are being re-opened by international combines. The shaft in the poem is one and many, like the persona: who is variously a foreign mining-engineer, myself, my father, dead miners related to me.”

The reference to the dead miners cannot help but evoke the Cornish folk tales alluding to the ‘knockers’ – ghosts of miners who had died in the shafts that according to some stories helped the living miners, and according to others killed them, and in all are reported to be the source of the ominous knocking noises often heard within the mines. Thomas’ interest in Celtic, and particularly Cornish folklore continues into his first-written, second-published novel Birthstone. The novel tells of three holiday-makers in Cornwall, one an Irish ‘spinster’ with demonic alter egos, the other two an incestuous American mother and son of Cornish heritage. The trio crawl through the megalithic Mên-an-Tol in Penzance and find themselves in an alternate universe where ageing is either reversed or accelerated, and incest is apparently accepted. For those unfamiliar, Mên-an-Tol is a Bronze-age ‘holed stone’ associated with ancient fertility rituals, though Birthstone’s geriatric mother not incorrectly refers to it as an “Old stone cunt”. Birthstone is a classic folk-horror, embellishing traditional folk tales with, as the blurb puts it “absurd, erotic, and often violent results”. Cornwall, folk-horror, dead miners, ancient stones, one cannot help but think of Cornish film-maker Mark Jenkin’s latest feature Enys Men. Indeed with Enys Men (or ‘Stone Island’) Jenkin joins Thomas in the elite of Cornish artists for his similarly masterful way of taking something as invariably consistent as a several thousand year old rock and transforming it into an ever-changing, deeply unsettling force. Thomas and Jenkin seem to have shared a mutual understanding that folk-horror is in its very essence a perversion of the traditional and the ancient, be that stones or customs or tales, and their resulting poems/films/novels are appropriately surreal, and often appropriately terrifying.

“I have become terrified of art. It is the fatal Oedipal crossroads where dreams, love, and death meet. Pasternak’s Zhivago reflected that art is always meditating upon death, and thereby creating life. But the opposite is equally true."

DM Thomas – Memories And Hallucinations

Thomas opens his memoir with this statement, and closes the chapter somewhat suspicious that The White Hotel has played a part in the death of his therapist’s father, or else perhaps predicted it. It’s an oddly final point for an opening line, and one that is telling of what is perhaps his most secret obsession. Known for his obsession with death, his novels often fixate upon the subject (thereby creating life), but one of his less discussed obsessions was his fervent fixation with life (thereby creating death, according to reverse Pasternak logic). Thomas indulged himself with life. He indulged in beauty, poetry, love, and in cigarettes and women. He had four wives and as soon as one left or died he took another. It would appear from his own account that he was almost always making love, or else otherwise, occasionally writing poetry.

“Some poems have no beginning and no end.”

DM Thomas – ‘Smile’

Donald Michael Thomas died on 26 March 2023. May he rest in peace.