Moss Icon didn’t invent a genre, but they might just have cast a longer shadow over that genre than any of its actual Ground Zero participants. They came from Annapolis in Maryland and took their first steps in 1986, putting them just out of time and place with emo: the scene up in Washington DC which harboured a small cluster of hardcore punks in their early twenties, taking on wider influences and adopting a more thoughtful, sensitive outlook. The bands were typically shortlived and took a dim view of ‘emo’ or ‘emocore’ as a descriptor, so naturally that was the last we ever heard of the term.

Or not: etymologically speaking, emo spawned a monster which anyone wedded to its prototypical definition had completely lost control of twenty years ago. I’m not old (or American) enough to have had a contemporary clue about Rites Of Spring and their DC peers’ self-styled ‘revolution summer’, or even the nationwide network of DIY bands who resculpted this music in bizarre shapes from the early 90s onwards. What I would though suggest is that those later bands – and hundreds or more who traded in the 21st century, by which time I was in the process of catching up – owe more to the delirious, misshapen hysteria of Moss Icon than most of what preceded them.

A four-piece of Monica DiGialleonardo, Mark Laurence, Tonie Joy and Jonathan Vance for most of their existence, Moss Icon disbanded in 1991 after releasing three singles and one side of a split LP. They rarely played non-local shows and, like a lot of bands, reckoned with ambitions beyond what their chaotic reality could offer. Vance, the band’s vocalist who came to Moss Icon as an amateur poet, had a restless spirit that put paid to any ambitions of a hard-touring lifestyle. They did however record an entire album, the ten-song, 42-minute Lyburnum Wits End Liberation Fly (the title derives from lyrics of Vance’s, but beyond that its meaning is entirely unclear), in three sessions during 1988. Its eventual release in 1993 (hence this being an ‘anniversary edition’) foreshadowed a voracious revival, and reinvention, of emo as a music and an ethos. By no means with the band’s assistance, but needless to say, when you put up art for public consumption you cede control of people’s reactions.

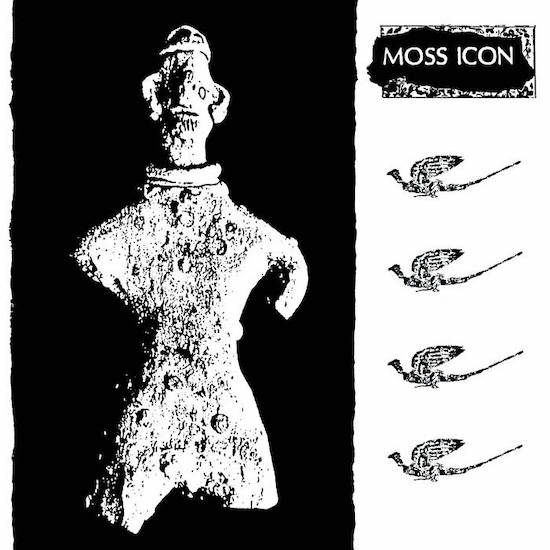

Lyburnum Wits End Liberation Fly has been out of print since the late 1990s: this is a technically correct statement which speaks to its creators’ strong desire to present this precisely as they intended. Vermiform Records, founded by Sam McPheeters from Born Against (a band Tonie Joy joined for a brief period), gave it life but ceased operations in the early 2000s; their 1997 CD issue of the album remained easy enough to pick up, but had shorted the title to Lyburnum on the spine and added songs from various other releases totalling nearly 70 minutes. That’s a lot of Moss Icon to chow down on, which applies even more to the double-CD/triple-LP Complete Discography Temporary Residence put out in 2012. Yes, it’s a fairly simple task to portion the music out into its original segments, but also decent behaviour to assume some artistic significance to it as a set of discrete objects. (Also, the vinyl version of the discography now sells for a similar low-three-figure amount as the original Vermiform LP.) Temporary Residence are also handling this latest reissue, and having already remastered the band’s whole canon, have modified the album’s artwork so it looks exactly like the band wanted. Although this does spotlight its – surely unintentional – resemblance to the sole album by Embrace, the other major name associated with DC’s ‘revolution summer’.

Like so many precursory pieces of art, in the long view this album sits far removed from what followed it, a patchwork of rangy influences which take a degree of lateral thinking to make fit. Its title track, which opens the second side, lasts over 11 minutes and swerves notions of bloat by rarely scaling back the intensity. Yet it’s textured, and instrumentally fluid, drummer Laurence contributing some especially fine parts – and though the clean, melodic guitar break which enters at 3:50 could sit nicely on many, largely ‘unpunk’ recordings, I hear Michael Rother in Neu! even as Moss Icon’s wild-eyed explorations put paid to that within 60 seconds. Vance free-associates a glut of Christian imagery, affecting the guise of some preacher in the midst of a lucid dreaming episode. (In this respect, the side’s penultimate ‘As Afterwards The Words Still Ring’ is its miniature cousin, with lines like “Altar you rise up my father / Down past ankle and from his rib and from his bone,” over aggro jangle and pre-post-rock guitar brood.)

Lyburnum’s other songs are more compact, from a little under two minutes to a little over five – that is to say, often drawn-out by the aggressively cursory standards that had been established, and remain in place, for hardcore punk. Is this actually a hardcore record; were Moss Icon a hardcore band? Yes, in parts: many of the more apoplectic vocal spots, or fragments of chugging guitar that might have been swiped from a Revelation Records release of the era. This, mind, is the ‘curate’s egg’ interpretation, and I’m not sure there can be a partially hardcore song. Yet all this does permit us to consider the litany of bands who, circa 1988, were using a hardcore grounding as a springboard even as others strove to codify it and make it more rule-bound. ‘Mirror’ is roughly contemporaneous, as a recording, with the first Fugazi EP, and that introductory riff is cut from the same cloth as its deathless opening track, ‘Waiting Room’. It sits within a rather more abstract frame, though, with Joy swapping out this downtuned, rhythmic style for a spindly, vaguely eerie solo. Vance’s lyrical tack could almost pass for a sarcastic inversion of the American straight-edge scene, then youthful, that talked – as this song does – of brotherhood, respect and strength. “We’re one and the same, and I hate you / Because we’re one and the same.”

‘Locket’ bears similarities to ‘Mirror’ in the way it stakes everything on the immensity of its central riff, which is a sort of denuded funk played in an uncomfortably claustrophobic style, maybe traceable to earlyish Sonic Youth. If Vance’s spoken lyrics like “Today there was a vision / Of a house burning on a television” are suitably Thurston Moore-ish groovy-sounding guff, then the near-tearful delivery of his closing plea – “Would you talk to me as if I could be real to you?” – is as uncanny a blueprint as anything for a movement of implausibly histrionic 90s emo bands, the sort who (in the recent words of Tonie Joy) “thought making 500 records in a burlap sack with a potato print on it was some pious statement”.

The first place I ever read the name Moss Icon was in a 1995 issue of the NME, which might also have been the only time they were mentioned in that publication, and was courtesy of Graham Coxon from Blur, who included MI’s ‘Kick The Can’ on a list of his current favourite songs. The list had been written on a typewriter, a somewhat trite nod to underground zine aesthetics that I found quite cool and intriguing, aged 15. ‘Kick The Can’ is, equally, one of the band’s shorter songs and one of its more tonally expansive – Joy’s guitar isn’t psychedelic exactly, but has a sort of frazzled, sun-bleached quality that sits nicely with Vance’s surreal tales of alienation in the desert (“I dressed up a cactus as a clown / And on his spiny face I painted a frown”).

Perhaps the four members on this recording, all playing in their first band of significance, did not aim to find new musical paradigms – though they did so more than intended – but they were audibly experimenting, and often the structures they build collapse. ‘I’m Back Sleeping Or Fucking Or Something’ is redfaced fits and flashbombs tossed around an enclosed space, yet bassist Digialleonardo, a stolid rhythmic weight dead centre, might be the performer that really makes this song – or, at least, holds it together – with a Factory Records bassline. She joined Moss Icon when they first reformed in 2001, but was absent for gigs in later years (the band’s last live performance to date was a 2012 fest in Austin) and, like Laurence and Vance, appears to have recorded little or no music in the last 30 years.

Guitarist Joy, conversely, has rarely ducked out of the rock underground to this day, moving to Baltimore after Moss Icon folded and twisting hardcore to his own devices in Universal Order Of Armageddon. Most recently, he and that band’s singer have made hairy psych blooze as Rogue Conjurer, whose first and currently only release is on a noise label from Minnesota. At any rate he hasn’t allowed Moss Icon to define his musical legacy, any more than the legacy of emo should be permitted to define Moss Icon.

Laburnum Wits End Liberation Fly is out now on Temporary Residence Ltd.