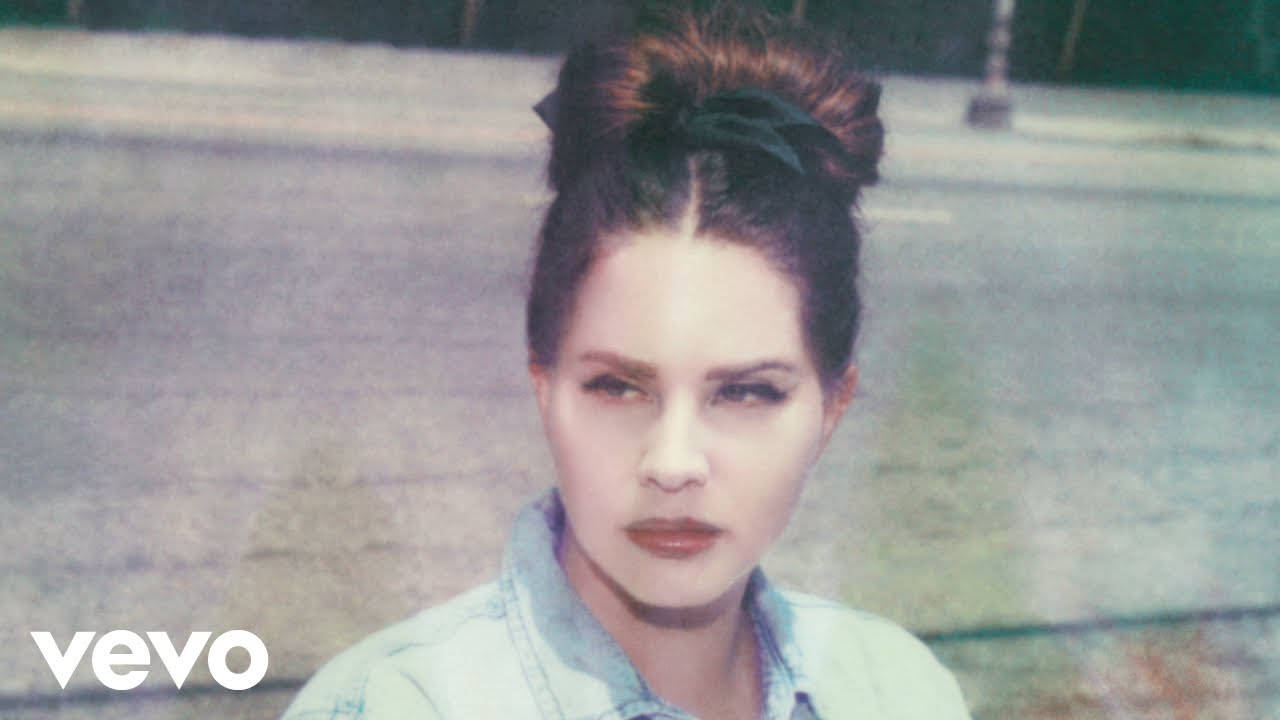

Lana Del Rey photo by Neil Krug

For many years, Lana Del Rey’s music has felt very close to me, tracing masochistic, romantic liaisons and loves that were so complex, addictive and nonsensical as to seem at times shameful. She didn’t just write one album about emotionally unavailable or diabolical men, she wrote nine; she was unapologetic in her need to express, untangle and live within this tortured, and yet sweet space. She succumbed and sung about weakness, about feeling strong in her surrender; discarded neat ideas about healthy aspirations and relationships even as she remained seemingly loyal to an Americanised romantic dream, with its picket fences, diamonds and delirium. She sang about Jesus, and also cocaine; she loved the bad boys, and she loved herself, too. Masochism fed the music, and I began to wonder if there could be music without this self-sacrifice, perhaps even a sort of drawn-out self-betrayal — whether drama of this painful kind was crucial to the strange, euphoric harmony she created when she recollected it in verse.

On her latest album, however, something has shifted, and it is entrancing. It’s not so much that these previous concerns have disappeared, just that the music is infused with a new peacefulness and light, a more overtly spiritual quietude and joy. In ‘The Grants’, the first track, instead of singing about “doin’ time”, she is “doin’ the hard stuff, I’m doing my time / I’m doing it for us, for our family time.” Somewhere between a gospel song and a lullaby, she sings of her pastor telling her that when we die, we only take our memories with us — and so, she is taking her memories of her family: “my sister’s first-born child … my grandmother’s last smile, it’s a beautiful life, remember that too for me.”

This could all be a little too sweet (the third track is also called ‘Sweet’, and is similarly ethereal and spiritual), but the album spreads out in other directions. In ‘A&W’, the mood shifts again — “Call him up, come into my bedroom / Ended up, we fuck on the hotel floor / It’s not about havin’ someone to love me anymore / This is the experience of being an American whore.” You could say that Del Rey is exploring the Madonna / Whore complex she has always embraced, but beneath this obvious, and honestly humorous dichotomy, there is a convincing self-confidence — along with a romantic gallows humour. She has apparently moved beyond wanting to be loved, at least for one song. She tells this guy, “Your mum called, I told her, you’re fucking up big time,” as she descends into a delirious, glorious, seductive dissonance, and also, I guess, a kind of cognitive dissonance, too. “I don’t care,” she sings, “I’ve already lost my mind.” And later, in ‘Candy Necklace’, more dreamlike, delirious, slightly fucked-up joy: “I feel lucky, white noise coming out of my brain.”

I love the chaos of these careful choices that are revealed as the album plays — like a set of tarot cards, songs jarring in their diverging meanings, and yet altogether creating a vision that is revealing, in the realms of its own esoteric logic. Del Rey, as she recently divulged to Rolling Stone, sees a psychic once a week, as well as a pastor, one would assume, and there is again a gleefulness and mischief in this combination, this grouping of spirits, as it were.

For all this playfulness, though, the existential questions are real, and it seems as though she is coming to terms with the romantic and masochistic tendencies that inspired previous work, linking it into spiritual concerns this time. In the ‘Judah Smith interlude’, a mesmerising and yet controversial track that samples a sermon by the Lead Pastor of The City Church in Seattle, Washington, these lines stand out: “In this cosmic glory, why are you so fascinating? / I want to be a man of love but I’m a man of lust.” She seems genuinely to be grappling with the greater existential questions, and the seeming futility of random love affairs and self-sabotage within that. This preaching, slightly muffled and distant, serves to disrupt and redirect the dream-like Disney fantasies evoked in previous tracks. Romanticism, religion and mysticism all entangle, though this feels less fetishistic than in previous work, more genuine.

She asks unnamed lovers, “Do you want to marry me? You can find me where no one will be,” and she talks about her family again, her anxieties — “Charlie, stop smoking … Caroline will you be with me, will the baby be ok? Will I have one of my own? Can I handle it? It’s a shame that we die.” Though there is a real teasing humour in parts of the album, there remains a more mature, heartfelt undercurrent of anguish and acceptance, too. In ‘Kintsugi’, she reveals, “I can’t say I run when things get hard. I just don’t trust myself with my own heart … There’s nothing to do except knowing this is how the light gets in.”

The light getting in is romantic and spiritual and it reveals itself gently through the tracks. In an old-school, crooning duet with Father John Misty, ‘Let The Light In’, it’s most overt: “Look at us, you and me, back at it again … Turn your light on.” This involvement of other artists, too (also John Baptise, Bleachers and Tommy Genesis, and her producer, Jack Antonoff’s wife, actress Margaret Qualley) – not to mention the references to her family — gives a very intimate, touching atmosphere, as if she has captured voices close to her the way we take everyday photographs of friends and family, collaged along with her diaristic confessions and dreams. She’s taken the visual techniques of her early videos, with all their implied intimacy and nostalgia, and used them in the audio itself, ranging from muffled laughter, as if Del Rey were in the pews of a church, to moments of jazz and psychedelic dissonance, to casual, flippant lyrics, about vaping and driving around. Lana feels like an old friend, and this is an album of real love songs — vulnerable and gentle and also deliriously sweet. By the end, inevitably, I’m entranced. I’m in some sort of love.

The Fear by Christiana Spens is published by Repeater Books