Cat Anderson. Photo by Francine Winham

The influence of Tumblr may have waned in recent years, but for many of my generation it remains an occasional portal to some truly sublime works of art. The jazz photography of Francine Winham sits firmly in that category, and Tumblr is the place where I first discovered it. Winham’s work would frequently appear on my feed leaving me bedazzled, yet she was rarely credited on these posts. From the level of engagement, her photography quite clearly captured the minds of many. It became apparent to me, that despite the interest in her photography, the many who engaged were, and still are, unaware of who the photographer was. After some research, I found a photograph of Cootie Williams at Newport Jazz Festival in 1959 via blog page the1959project with Winham’s named credited and that distinguishable technique. I had found her! It speaks volumes that images captured in an instant over half a century ago continue to be shared so widely by so many on a platform used mostly by young Millennials and Zoomers.

Fascinated by the pictures I found online, I wanted to gain some understanding of Winham as an artist and as a person. I started connecting with her family and friends, trying to piece together the life of an artist who shot Miles Davis and Dizzy Gillespie at their 1960s peak, a woman responsible for the sleeves to classic albums by John Martyn and Traffic, a key player in the birth of Island Records and the explosion of interest in Jamaican music beyond the Caribbean. My research led me to a Zoom call with Winham’s childhood friend, Carole Van Wieck (née Adler, the daughter of legendary harmonica player Larry Adler) and to a long interview with the forever animated Jamaican actor, photographer, filmmaker and model, Esther Anderson at her home in Chelsea, who became close friends with Winham during the 1960s. I stepped into what felt like a filmset, visiting Winham’s family estate Joldwynds in the Surrey countryside, a beautiful Grade II Listed home bathed in sunshine on a crisp April morning, half expecting someone to shout “cut!” There I spoke to the painter Philippa Heimann, Winham’s niece, as well as her friends Jonathan Pershal (filmmaker) and Ben Hardy (director) who worked with and were mentored by Winham. I learnt about the woman behind those phenomenal jazz photographs I’d seen on social media – and in particular the groundbreaking method she called her ‘fever technique’.

Winham was born in London in 1937. With Europe on the brink of war, the Winham family evacuated stateside to Colorado, marking the beginnings of her affinity with the United States. By the late 1940s and into the 1950s, with the war now over, the Winhams moved back to a London whose social landscape was evolving rapidly.

For Winham, the swinging 60s was an exciting time to be young. I asked Esther Anderson about Winham in her youth around this time and her answer came as no surprise to me. “Francine was a bohemian and we were very much into bohemia,” she says. “The way we dressed, wearing men’s trousers and sandals. This is the early 1960s you know!” By now, Anderson is waving her hands around and grinning. “When we were young, we used to go to a place to dance called The Saddle Room. Winham was so beautiful, people used to think she was Princess Margaret!” By this point, Winham was getting heavily into ska and blue beat music, and had just acquired her first camera as a gift from her father.

Francine Winham

It was around this time that Winham met Chris Blackwell. The English producer needed a personal assistant to help with his fledgling Island Records. Winham spent time photographing artists for Blackwell’s label, but she soon began developing a desire to experience Jamaican culture first hand. Speaking to the relatives and friends of Winham, the impression given is that she had a lifelong desire for exploration, and wasn’t one to be satisfied by home comforts. An opportunity presented itself for Winham to travel to Caribbean, and she, along with her friend Carole Van Wieck, grabbed it with both hands. Winham was desperate to experience Jamaican culture whilst Van Wieck had been commissioned to write for British society publication Queen Magazine. Winham, too, had been commissioned to shoot for the monthly woman’s magazine Harper’s Bazaar. But as soon as they arrived, their plans ran head first into the course of history.

“We’re out in the car and it’s the first day,” Van Wieck recalls. “I noticed we were the only car on the road, and I see all the cars are parked to the side of the road with groups of people standing beside each car. I say to the driver, why aren’t there any other cars on the road? The driver stops, goes to investigate and comes back crying. He tells us John F. Kennedy has been shot dead. Fran and I were absolutely distraught, we couldn’t believe it.”

Winham was a renegade, an anomaly, given her white, middle-class upbringing. The perception of Jamaica during the 1960s, rooted in the kind of racist, imperialist sentiments then commonplace in the UK, was of a violent place. Winham typically ignored all that, and focused entirely of the unique beauty Jamaican culture bore. “She heard about reggae music and that’s the music that brought her there,” Jonathan Pershal says. “She involved herself in the community … The beach, touristy stuff did not interest her. It was the culture.” There is a sincerity in Pershal’s voice. I get the impression that despite her desire for exploration, Winham was overtly aware of her privileges as a white person entering Black spaces, and sought to authentically experience a culture that moved her so much.

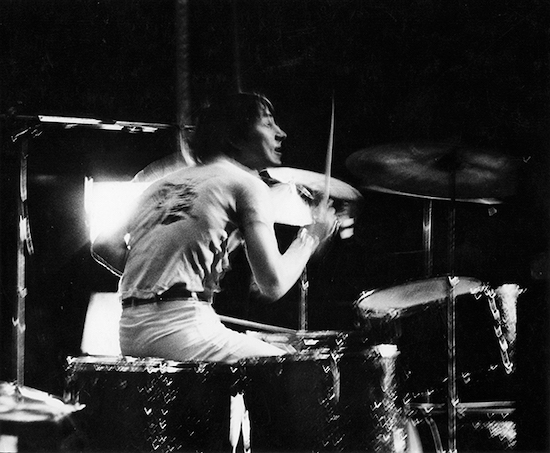

Keith Moon. Photo by Francine Winham

Whilst in Jamaica, Winham, along with Anderson, heavily assisted Blackwell in getting Island Records off the ground – even selling records from the back of his car. Anderson would then facilitate bringing artists to the UK from Jamaica, taking responsibility for chaperoning artists as they acclimatised to London. This was the very beginning of a huge wave of influence of Jamaican on the music and film industry landscape with the arrival of the likes of Jimmy Cliff and Millie Small.

Winham steadily became more at one with her camera, and began to shoot more adventurously. By the mid-1960s, jazz was at a creative peak. Its cultural epicentre lay in New York City, and of course Winham – along with Van Wieck – got themselves to NYC in a hurry. “My Dad [Winham’s brother in law] was a huge jazz fan as a boy,” Philippa Heimann tells me. “My mother, brother, father and Winham were all very good friends, and they would go to jazz clubs together.” There is a sense of pride in Heiman’s voice. Winham found jazz intoxicating, particularly fuelled by the way in which jazz artists were able to communicate a way of being that felt beautifully alien to many. Winham arrived in time to see legendary performances by the likes of Miles Davis, John Coltrane, Ella Fitzgerald, Nina Simone, Thelonious Monk, Duke Ellington, Cat Anderson, Dizzy Gillespie, and more. Perhaps Winham’s affinity to jazz music was always to be, and her relocation to New York to be at the epicentre of the scene carried with it an air of inevitability.

Lette Mbulu. Photo by Francine Winham

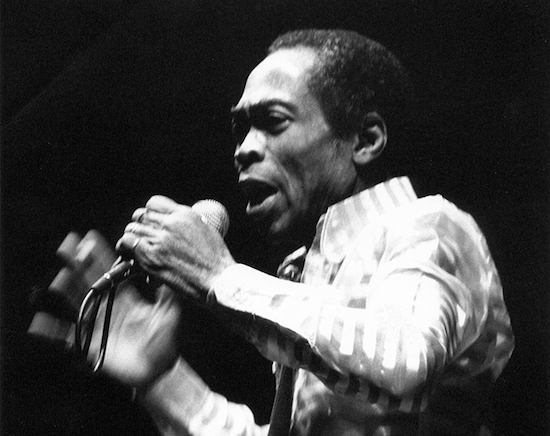

During this era came perhaps the most stunning photography of Winham’s career. Her style of shooting was entirely unique, and Winham demonstrated the ability to create a method of image-making that beautifully illustrated the interconnected story of jazz and African-American people. She shot predominantly in black-and-white, though her pictures carried with them a sense of the ethereal. Take for instance Winham’s shot of Cat Anderson, known for his emphatic cadenza solos and high triple C, as he blows into his trumpet. The image Winham took of him at the 1965 Newport Jazz Festival is distorted and fantastical. However, this distorted image is not one that reflects on poor photography; in fact, it is a stroke of genius. The streaks of light owing to the flash of the camera against the brass instrument are deliberate, caused by Winham reducing the shutter speed and moving the camera as she took the photograph. The result is the communication of something beyond the perception of the naked eye – both a figment of Winham’s imagination but also a true depiction of how the music makes you feel.

This style of photography Winham would go on to coin the fever technique. “I asked her how she did that, and she said she moves the camera [as she takes the shot],” Anderson says in a casual tone, as if to suggest Winham perhaps did not realise just how incredible the act was. “It was her own imagination, she wasn’t following anybody.” The result is the capturing of the artist’s virtuoso being, the ability to convey a level of intimacy and emotional resonance perhaps not spotted in real time. The freeze frame, in the moment in which the artist reaches a realm whereby it is only them and their instrument, their existence. Their instrument becomes the communicator of all sensory experience in the context of their relation to the world that is graciously put forward before a crowd – Winham is able to capture all that in one technique. I ask Heimann what she feels when observing some of Winham’s photography, and her response is poignant: “I think with a lot of her photos, you can hear the music. It’s like you’re being taken in by [the musician’s] aura.”

Dizzy Gillespie. Photo by Francine Winham

The photos are able to provide us with privileged proximity to their mind and process. “You’re being drawn into their world, and in doing so, she is capturing their essence,” says Pershal as he gazes at one of Winham’s photographs. “You feel their spirit, as well as their oneness with the instrument.”

“It’s not just the music, but the physicality of making that music too,” Pershal continues. Typically we’d see the exasperated faces of the artists as they performed in these photographs. We gain an understanding that their physical presence is truly representative of where, spiritually, the artists find themselves when on stage. Producing jazz music requires an uncompromising search of self, a narration of harrowing experiences through music, and the distortion in the photographs captures this. Moreover, what is also put forward is the musicality .“It created the feeling as if the notes were visible,” Anderson says. “It was just wonderful.” As we speak, Anderson moves to clasp her hands together, just above her heart, and smiles. I am suddenly, and very vividly, presented with expressions that show me just how much Winham meant to Anderson.

The streaks of light that emanate from the instrument are musical in themselves, and you are immersed into the room in which the performance is taking place. Those visceral moments of vulnerability captured in time, at a point of which the artist is in their zone, pushing their core to extreme emotional depths. It is a testament to the unique artistic eye Winham had to capture all this with her limited window of opportunity. Dizzy Gillespie’s cheeks blown up during his performances was his occupational signature, but also an outward sign of just how far these artists were willing to push themselves in the name of music.

John Lamb. Photo by Francine Winham

What you will notice is that there is a distinct quality about these photographs – a warmth that somehow is able to convey the labour of love that is music. Her photography, says Ben Hardy, “breaks the barrier between the artist and the audience. It feels like you are there, part of the picture, the movement and atmosphere.” He looks to the distance as he speaks, appreciative of the artistry of his old friend and mentor.

A combination of sixth sense, impeccable timing and a respect for the craft of artists meant Winham could, in a single frame – caught in fractions of a second – share with us all a specific moment of intense vulnerability from the perspective of the artist. The shot offers glimpse into their uncompromising process. “They are very atmospheric,” Pershal says of Winham’s photos. “The viewer is active instead of passive. A still photograph would seek to catch the essence, whereas Francine’s capture something more ephemeral,” Pershal continues.

The mid-1960s was also a time of fierce battles against the Jim Crow era, representing an extremely turbulent and traumatic time in American history. Jazz offered a creative outlet against the backdrop of the mass dehumanisation of Black people and the denial of human rights. “We’d go to Miles Davis shows and if it were a white audience, he’d play with his back to the audience,” Van Wieck recalls. Playing to an audience which Miles saw as a mirror of his pain perhaps felt like a betrayal of his own self, but perhaps too this was a statement from Miles that the plight of Black people must reach some sort of endgame. “There was an anger in the Black musicians that was palpable, and Francine gets that in her pictures,” Van Wieck continues staunchly.

Fela Kuti. Photo by Francine Winham

Winham did not ignore the marginalising social conditions that existed alongside the artists and culture she photographed. She was an activist both in her outward facing life, and also in her personal life. This often reflected in her photography, which included the photos she took of Vietnam war rallies in America, particularly focused on the children participating to highlight the level of manipulation that occurred. “She was moving in the political left wing that wanted change. Change that absolutely had to happen. It wasn’t like, let’s wait until tomorrow. It happens now,” Pershal says quite fiercely, reflecting Winham’s own energy. Winham existed during a time when bigotry reigned, and she saw art and activism as a mechanism to combat them.

Winham always bore the heart of one who sought to bring the best out of those she came across. “Francine was always a greater encourager of artists, and particularly young people,” says Heimann who was herself once under Winham’s wing. “What you’d particularly notice when you were a child, was the sense of equality. How some adults talk to children like they are children, and other adults talk to children like they are people. Francine always would talk to one as if one had their own story in life.”

Winham was able to instil a sense of agency into children, and assist them in developing their beliefs and creative desires, allowing them to express how they see the world in their own way. Winham was particularly skilful in encouraging the expression of one’s own individuality, just as she did with her own. Whoever Winham met, she had a knack of spotting a talent in them that they may not yet see in themselves, she took it upon herself to facilitate and encourage those she saw something special in. “I was living in Cheyne Walk [in Chelsea, West London] when I met Francine,” Anderson says smiling. “She was my first English friend [after moving from Jamaica]. I would meet her all the time. We’d go everywhere together when we were teenagers. Then she started encouraging me that I should take up acting. She said that I was so animated, and that I wasn’t afraid to express myself. And that’s how I trained as an actress. Then she started photographing me, and making me feel right about myself.”

Francine Winham

Anderson would prove to be one of many Winham took under her wing and sought to see excel in whatever endeavour they were interested in. Anderson went on to play a starring role in the 1973 film A Warm December alongside Sidney Poitier. Despite Anderson’s self-driven personality, she too benefitted from Winham’s affirming presence. “Francine showed me how to use a camera, how to mix the liquids [used in film processing], lighting. She gave me cameras and said, go on, go off to Germany. So I went to Germany and took tons of pictures. That was my first freelance gig.”

“The more I got into photography,” Anderson continues, “I realised [Francine] opened up something inside of me that no one had done before to show me that I have many gifts and how I can tap into them.” One of Winham’s greatest gifts was her ability to uplift others. Besides her captivating photography, the influence she had on those around her remains a key part of her legacy.

Winham’s photography carries a special effervescence that gets right to the heart of my passion for the arts. I was immediately drawn to her work. To this day, these images are continually posted around social media platforms like Pinterest and Tumblr, popular amongst a generation of Millennials and Gen-Zs too young to remember the era they were created in and the artists captured therein. Winham’s work endures not just because of who she photographed, but more emphatically how she photographed them. Many, like me, have come across Winham’s work without knowing the photographer. Her ‘fever technique’ carries a moving quality. When I encounter it, I feel immersed in the performance there captured. I am no longer just an observer. That is special, and that is Francine Winham.