This text is vocalist, composer and improviser Alya Al-Sultani’s contribution to a series of essays, commissioned by REMAIIN (Radical European Music and its Intercultural Nature), a project that investigates non-European cultural influences on the experimental, avant-garde and innovative music of the present and the past. It is co-funded by the ‘Creative Europe’ programme of the European Union.

Alya Al-Sultani is a dramatic soprano, composer of opera and producer based in London, UK. Her first musical experiences were Iraqi folk songs sung by her great grandmother and radio broadcasts of classical Arabic music. After leaving Iraq during the Iran-Iraq war, her family settled in Tottenham, North London where she began to discover the incredible new sounds of the ’80s, hip hop, jazz and music from the Caribbean. Apart from working on her own projects, Al-Sultani enjoys debuting new music for contemporary composers and experimenting with opera, including the integration of improvisation techniques, microtonal ideas and Middle Eastern influences. Jazz is a constant thread through all of the music she makes – method, aesthetic, structure, rebellion, politics.

As the political landscape continues to fall towards one where freedom of movement is a seen as a threat rather than an opportunity, where visas are no longer granted to artists, despite having families and careers in their home countries, because they "cannot demonstrate sufficient reason to return," and where minority artists feel the pressure of right wing walls closing in, the intercultural making of music is on the systemic level, closely tied to questions of power and on the personal level, to questions of integration.

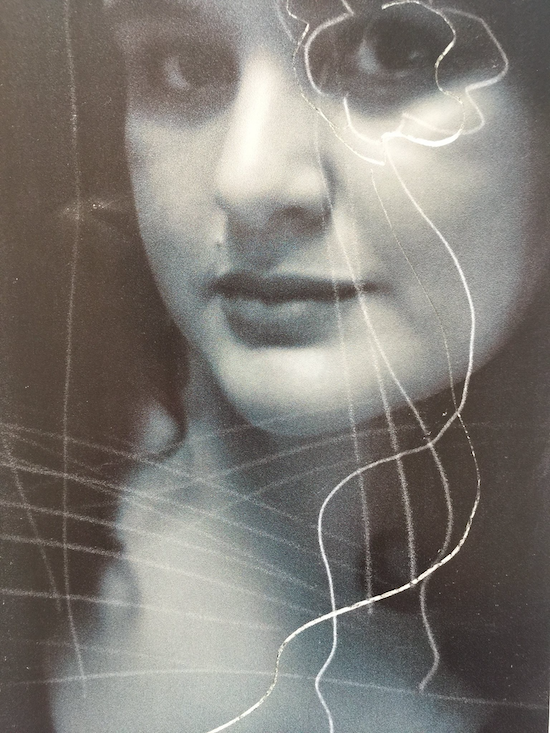

When I say integration, I am speaking psychoanalytically – integration as a process of bringing together the fragments of the self and the shedding of false selves. We all grapple with false selves in different ways, but I want to look especially at that complexity as an immigrant / refugee and minoritised person.

Why do we develop a false self? To protect us from pain, prevent the repetition of developmental and other trauma, to seek belonging through conformity, to be loved. For minoritised people, also to hide from the oppressor by seeking shelter within him. The false self is a shield, an instrument of human survival, behind which millions of people live and die.

In the summer of 2014, I was stood on St. John Street in Farringdon, London. I can only describe the feeling as being unable to take another step. The night before, I had had a terrible gig. At the time, and for a few years before that, I was attempting to explore what was a new concept to me, improvisation, through the medium of the American Songbook, and this gig had poor sound, a disinterested house trio and a fragmented me, who didn’t know who I was, trying to deliver music as I thought it should be delivered. I had a horrible time and so did the audience. So there I was the next morning, near my flat, unable to take another step. I called my mentor and friend, vibraphonist, improviser and composer, Corey Mwamba. I told him about my terrible gig. He responded: "An Iraqi woman is having trouble with the American Songbook. I wonder why that is." I was offended – why can’t I, an Iraqi woman, sing this music? We talked about authenticity, what finding your sound requires and how integration of the person of the artist and the artist is fundamental to that. He wasn’t saying, "You can’t." He was saying, "You shouldn’t," and he was right.

What I had been grappling with to that point is permission. My immigrant self lacked permission in many things, including deciding for myself what was good and where excellence was located. Classically-trained, I felt safe in the unquestionable (?) excellence of classical music and in order to explore improvisation, I sheltered myself again, within the framework of another Western music system, albeit one that I had yet to understand the history and politics of.

Much of the music that has influenced me through my lifetime came to me through human connections and friendships, and accidents. Arriving from Basrah with Iraqi and Arabic music in my ears to the sudden onslaught of ’80s synth pop, Caribbean music, Kate Bush, Western classical, hip hop, garage, electronic music, all sounds that intermingled within me and continue to do so. What I am and have always been is a vessel of intercultural exchange. But something about my place within the dominant culture created a hierarchy in my mind of what held value and what did not, where I could be a "serious musician," and where I could not. I felt less than myself and from that position, I could not find an authentic voice in music.

I didn’t know at the time that free improvisation existed. I thought jazz was the only medium within which improvisation could exist. This is testament to the narrow and rigid music education I had as a classical musician more than anything else. From 2015, I went on an intensive listening journey – Black Top, Yana, Maggie Nicols, Elaine Mitchener, John Edwards, Neil Charles, Dee Byrne, Rachel Musson, Cath Roberts, Mark Sanders, Jason Yarde. The quality of the British free improvisation scene was and is extraordinary.

In that same period, and soon after my conversation with Corey, I went to New York and recorded my first album, Chai Party. This was the first time, in many years, since the Gulf War of 1991, that I wore my Iraqi heritage explicitly. When the Gulf War started, my family became under threat of deportation and the climate became anti-Iraqi. We started to hide who we were and this, along with racism we experienced, resulted in a fragmentation within me, where I hid my ethnicity the best I could and internalised much of what was told to me about who I was as something bad and shameful.

Chai Party is made up of those fragments, yet to find their way together into integrated form. Arrangements of Iraqi folk music, going to the source, so to speak, but not then pushed through the filter of my immigration experience, and contemporary jazz wordless pieces which were a first attempt was trying to create something new through the tools that jazz provides. It’s an album I love and that I am proud of because it signals my first step towards the shedding of a false self, a step in the right direction.

Three years later I went on stage at Cafe OTO, for my first ever free improvisation performance with the likes of Pat Thomas, Corey Mwamba, Rachel Musson, John Edwards and Mark Sanders. I remember that gig vividly – I was a beginner but I was lifted into infinite space, where my sound came from deep within my belly and my chest and I experienced artistic freedom for the first time. I remain grateful to every artist in that group who were so tender and generous and encouraging.

The reason I mention false selves at all is because I believe intercultural music-making requires false selves to be shed to work meaningfully. I would not have been able to have the same experience before I became aware of the structures I had built around me to keep me safe. An authentic meeting of cultures requires difficult questions to be asked of us or otherwise, one of us has to always play dress-up, literally and artistically, and it is usually the less powerful in the exchange. I have been through a full spectrum of contortion – orientalising myself, denying myself, refusing to sing in Arabic, singing only in Arabic, being the alluring one, being the one who denies access to the male gaze. I would like to make music with others who have also resolved or are suffering their contortions. How can I, for example, make meaningful music with someone who is offended by the fact of their privilege in the dominant culture? I can’t see how this is possible.

It is for this reason that I refuse certain collaborations and work and am very selective about who I work with – not because I am a diva, but because I am conscious of how power plays into my ability to seek freedom, and because over the last decade, I have been on a determined journey of integration and the shedding of my false self. This is not a linear process and in the wrong place, on the wrong project, with the wrong people, I can fall back into past structures that do not serve me.

In the UK, we are seeing the dominant culture raise its voice and flex its muscles when it comes to ethnic minorities, women and the LGBTQ community, with a twisted focus on the T. In response, the pressure is producing diamonds, young artists who arrive already fearless and older artists who have had enough. Everyone is less afraid – maybe because we survived our worst nightmares together – maybe because the digital age allows us to know we have likeminded kin all around the world – maybe because the dominant culture has resisted too hard and we have realised simultaneously that appeasement gets us nowhere.

I am enthralled and relieved by what I am seeing in the UK experimental music scene, that I struggle to describe but it feels like an exhale after holding our breath for a little too long. Multiple running streams into a river overflowing, bursting its banks, after heavy rainfall. Cells renewing. Anger as life force.