When in 2014 Paul Dunmall released Life In Four Parts with his sextet, the album gestured towards a moment of self-reflection, marking the British saxophonist’s 60th birthday and encompassing all the various styles of jazz and beyond that he had played throughout his career. Recorded two and a half decades earlier, in 1989, That’s My Life feels just as defining. It appears as an early announcement of what was to come and, in retrospect, a fascinating testament to Dunmall’s artistic vision.

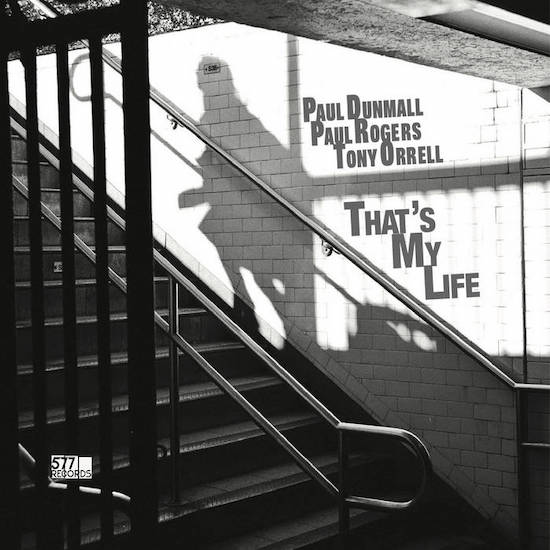

Like many of the best (free) jazz releases, the album is a live recording that captures Dunmall letting it rip accompanied by bassist Paul Rogers and drummer Tony Orrell – themselves stalwarts of the British scene – during a summer night at Bristol’s Albert Inn. At the time, they had already shared a rich musical history. Dunmall played with Orrell in local jazz band Spirit Level, while Rogers and he collaborated both as part of Mujician (with Tony Levin and Keith Tippett) and as a duo. Although this is the trio’s first and only released music, the three musicians would continue meeting together over the years. Divided into two long tracks, That’s My Life also acts as a curious document of the British jazz scene in general.

Its first part, the eponymous ‘That’s My Life’, is the more hermetic and visceral of the two pieces. With a clear lineage to US jazz, it shows Dunmall’s admiration for John Coltrane and connects him to the free improvisation sensibilities of contemporaries like Tippett, Kenny Wheeler, Evan Parker and Barry Guy. Dunmall gets everything going with a snaking melody played in the upper registers of his soprano saxophone. His tone is assured yet silky, always under control, but with a hint of wildfire underscoring his elongated notes. Meanwhile, Rogers and Orrell find themselves locked in a tight, repeating rhythm, the former pumping an endless double bass walkup and the latter laying down a skittering drum pattern. Gradually, things become freer and freer. The trio find a hint of a groove then disassemble it, while Dunmall shifts from lyrical birdsong-like phrasing to extended, skronking overtones.

In contrast to the Spontaneous Music Ensemble and AMM aura of the first part, ‘Marriage In India’ brings forth funk and African music traditions. At the heart of it, there’s a massive groove sustained by a sumptuous double bass riff, swaying tom-snare-cymbal rides and roaring saxophone licks. Naturally, the flow soon breaks free and falls apart. The initial high disperses into quiet, abstract fragments of free improv and several inspired solo spots, before ultimately ramping back up to full head-nodding force. As a whole, this is a curiously prescient cut that foreshadows the rise of trip hop and the hip hop and electronic music leanings that would come to flavour British jazz decades later. As Shabaka Hutchings put it when talking to The Wire in 2018, “if Paul Dunmall was twenty years younger and looked like Kamasi Washington, it’d be game over.”