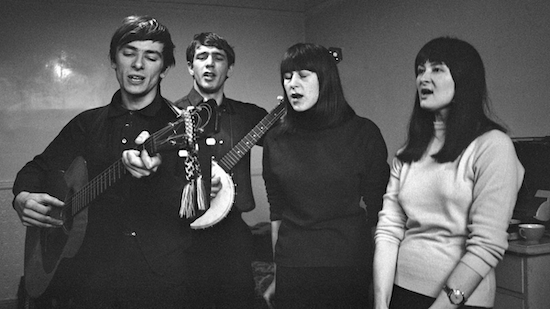

Photos by Brian Shuel

When I think of seasonal songs, I don’t think about The Watersons’ Frost And Fire straightaway. I think of ‘The Scarecrow’, a song from the extraordinary album they released seven years later, Bright Phoebus. It was originally written by youngest sister Lal, and sung on the LP by her older brother Mike, who made small alterations to the lyrics and added the last verse. Richard Thompson and Martin Carthy accompany him on delicate, dextrous guitars.

I think of ‘The Scarecrow’ straight away because it is my favourite song by any of the Watersons (among tough competition). I also mention it because this Autumn marks the fiftieth anniversary of Bright Phoebus’ release and because this wildly imaginative, macabre, playful and affecting collection of songs needs to be constantly revisited and replayed. Getting a copy through conventional channels is trickier.

Four years ago, Yorkshire label Celtic Music successfully sued Domino Records for copyright infringement, removing from sale a 2017 remastered reissue of the album. On a press release after that hearing, Celtic explained that they had purchased the rights to the album, and many other albums on the folk label, Leader, in 1990 (which had gone bust several years earlier, and bought by other companies in the interim). Celtic added their 2000 CD release had “been available ever since”.

I own one of these, a CD-R release with a photocopied cover and low sound quality, bought many years ago. On the date of submitting this feature, there is one copy of it available on Amazon via a site called Buy British for £73, and another on Discogs for £45. Celtic Music also has a one-page website, with an e-mail address and phone number. Approaches to both by friends to try and buy the CD in recent weeks have not yet received a reply.

Two tracks from Bright Phoebus were also licensed to Honest Jons Records’ Mark Ainley and John Williams in 2006 for only ten years. One of them gave its name to Never The Same: Leave-Taking From The British Folk Revival 1970-77, an anthology put together by Ainley and Williams. This collection is where I – and I assume many other fans who came to folk music in the 2000s – first heard them. People newly interested today can only hear ‘Red Wine Promises’ on Spotify, another track licensed for the 2006 anthology Anthems In Eden, or trawl YouTube.

In their post-court hearing press release, Celtic Music also promised a “programme of re-releases to cast new light on valuable folk music performances from the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s” in 2018. It remains eagerly awaited.

I also mention ‘The Scarecrow’ to show how well The Watersons understood the primal pull of the mystery of the turning of the seasons. The song begins one summer’s morn with a person roving out, seeing a scarecrow tied to a pole in a field of corn. It is an unsettling vision, his coat black, his head bare. Instantly, it sparks the darker realms of the imagination. Then comes the melancholy. “You’re only a bag of rags,” Waterson sings, with startling tenderness, “in an overall”.

The seasons wheel. Magical realism ignites. ‘The Scarecrow’ becomes an old man hanging; the wind wrings necks; the narrator begs to be laid down and loved by a bag of bones; a newborn is tied up by men dressed out in the blue and gold so gay (Mike added this verse, the men inspired by a local Morris troupe he knew). Mike returns to the summer at the end of the song, as if the seasons themselves are part of a mystifying, terrifying musical round. The heft in his voice and the cyclical strangeness of Lal’s melodic writing keep going.

Bright Phoebus is full of other astonishing shape-shifting tracks. ‘Red Wine Promises’, sung by the Watersons’ oldest sister Norma, transforms a drunken night out into a technicolour reverie. ‘Child Among The Weeds’, a wild lament of raven wings, young men leaving seeds and old men in rocking chairs, was written by Lal after the stillbirth of her baby daughter (a twin to her surviving son, musician Oliver Knight). ‘Never The Same’ tells us of Johnny who can’t play and Rosemary sitting in a shower of rain which will kill her; she’s coughing but nobody will get her. It is one of the most devastating visions of a world just after a nuclear bomb that I’ve ever heard, like a scene from Peter Watkins’ The War Game, delivered with detachment. “There were twenty-five jenny wrens sitting on a willow when the wind came in,” Lal tells us. “None of them could sing”.

I mention these songs at length because I want you to seek them out, play them often, listen loud, immerse yourself in their silty, bloody layers, pass them on. I want to make sure they keep living, for new fans as well as old, and that they are never lost.

I also mention these songs as I hear the roots of the directness in their delivery, and the boldness of their themes in Frost and Fire: A Calendar Of Ceremonial Folk Songs, reissued this Autumn by Topic Records, in a facsimile copy of its original edition. It was recorded by Bill Leader, the English recording engineer and record producer who had already worked with Ramblin’ Jack Elliott, Peggy Seeger and Bert Jansch. He saw The Watersons at a folk club in 1965, run, funnily enough, by Martin Carthy. (Martin and Norma got together in 1972, after recording ‘Red Wine Promises’ together for Bright Phoebus, a story later relayed to the world by their daughter, Eliza.)

Frost and Fire was recorded in Leader’s two-room flat in North Villas in Camden Town. At this point, The Watersons comprised big sister Norma, 26, Mike, 24, Lal, 22, and their second cousin, John Harrison. Their lives were captured in a 1966 film for TV, Travelling For a Living, directed by Derrick Knight, who had previously made adventurous public information films. Set in incredible monochrome with a dash of new wave shimmer, it is free to watch on the BFI Player online . The family look fabulous in it, Norma’s bob swinging into perfect Mary Quant points, Mike harbouring a wonky-toothed, Mark E Smith-like charisma, his wife a shadow of Broadcast’s Trish Keenan.

Post-war Hull glowers in the shadows. The band are no-nonsense as they discuss not fitting in with their neighbours, and going about their lives touring the country together in a van. Swap the outfits, turn the black-and-white to colour, and this could be a documentary about DIY ambassadors from the days of punk or post-punk. Fittingly, Frost And Fire became Melody Maker’s album of the year in 1965.

Like many punk and post-punk records, it is an uncompromising listen. The Watersons sing together more often in unison than in conventional four-part or contrapuntal harmonies. Little ornamentation softens the ends of their phrases. The effect is like being met by four horns on a shore, trying to target their words to the elements in straight, direct blasts.

It’s not pretty, but it is powerful. This style of singing cuts away any whimsy, or associations with quaintness, that often slip into expressions of folk culture. The Watersons lick these songs clean.

Many of the songs were suggested to the band by A.L. Lloyd, the self-taught folklorist who went on to become co-founder and artistic director of Topic Records and co-compile The Penguin Book Of English Folk Songs with Vaughan Williams. Mike Waterson once called him “a guru to us”; Lloyd also directed the subject matter of their songs. “We sang one and he said, ‘Mm, we shan’t use that one. It’s too subservient.”

It’s easy to forget how folk collectors were also editors with agendas. In some ways, it doesn’t matter here. The Watersons’ voices don’t suggest any penchant towards pliancy. They reject any sentimentality and schmaltz. They are unabashed, unpretentious dirty projectors.

Frost and Fire ’s track-listing begins in January with ‘Here We Come A-Wassailing’, a song found by the Roud Index of folk songs to have more than 127 “instances” around the UK. A.L Lloyd adds in the liner notes that this tune which has similar versions “scattered across Europe as far as the Balkans”, reminding the casual fan that traditional songs are not fixed, but like rocks in the sea, in motion across continents, battered and borne to new places, slowly being reshaped, yet surviving.

Many of these songs come with earthy lyrics. In their version, The Watersons call for bud and blossom to “bloom and bear”, not so that people may not starve, but “so we may have plenty of cider all next year”. ‘The Derby Ram’ comes next, a song once sung by groups of men house to house in midwinter, which tells of a huge, impressive ram (indeed, one of the men used to dress up as the animal as part of the fun). It overflows with innuendo: “yes, the horns that on this tup they grew, well they reached up to the moon/A little boy went up in January and he never got back till June”. The lyrics dig deeper when Mike Waterson sings it because never overplays it. His voice is deep, hoary and oddly handsome, crackling with effortless character. Richard Thompson said it seemed that Mike never breathed when he sang, and you hear this here.

Norma’s lead on the gorgeous ‘Jolly Old Hawk’, a Twelfth Night carol, has a similar effect on the listener. These songs don’t appear to emerge from the exertions of the lungs of these singers; they seem to exist within and without them. The delicate family harmony that unfolds around the lyric “his wings were grey” also has all the warmth of a grandparent’s arms.

Many lyrics here also remind us how older terms still survive. ‘Pace-egging Song’ refers to the Latin word for Easter which still has living relatives in Welsh and Cornish (Pace, Pasg and Pask), and French (Pâques). Several songs have biblical roots – ‘Seven Virgins (The Leaves of Life)’, ‘The Holly Bears A Berry’, ‘Herod And The Cock’ – showing how many folk songs come from the church as well as non-Christian traditions. Other songs with mysterious roots rouse, like the glorious ‘Hal-on-Tow’, a regular song at the greatest-named May Day ritual of all time, the Helston Furry Dance, still practised in the Cornish village every May.

But the songs that affect me most on this record are sung by Lal and Mike alone. On ‘Christmas Day Is Drawing Near’, Lal sings this moralising Christian song in a voice that suggests a heartbreaking submission to its sentiments. She surrenders to its mournful minor key, underlining the terrors of subservience. You hear the strange movements of the song’s melody in her songwriting in Bright Phoebus seven years later.

And in ‘John Barleycorn’, Mike Waterson sings of three men coming from the west, their fortunes for to try, making a solemn that John Barleycorn must die. They throw clods upon his head; they let him lie until the rain soaks him; they are amazed that he springs up again. The cycles of the seasons continue relentlessly, barbarously. The humans join in, their scythes sharp at his knee, grinding him between stones, fittingly seamlessly into the ecosystem.

As Mike’s voice roves out, I also hear the young man he was, the old man he became, the dead man he is now. I hear Lal’s voice, gone to the world for nearly 25 years, and the voice of her big sister Norma, quiet for less than a year. I think about the lovers of folk songs who say that the best songs will last purely on their own merit. I think about the people that make choices that control how others are allowed to listen to them.

We should all ring a bell for these songs, recalling the words that were sung, the corn that they sowed. I hope that someone out there will be catching them, jumping between Frost And Fire, seeing the bright phoebuses shining down on us, for the very first time.

A new reissue of The Watersons’ Frost And Fire: A Calendar Of Ritual And Magical Songs is out now via Topic Records