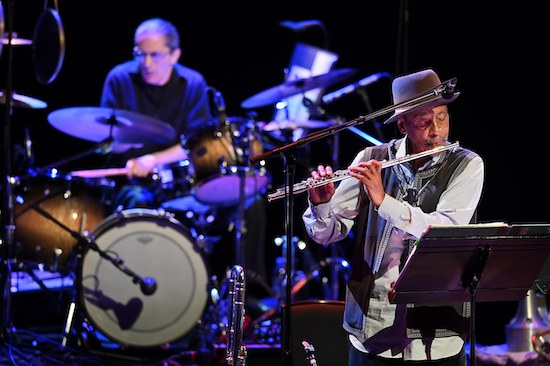

Henry Threadgill. Photos by Mark Allan / Barbican

The Association For The Advancement Of Creative Musicians is arguably the most important musical collective of the last 60 years. The most enduring of the autonomous organisations to emerge from the 1960s jazz avant-garde, the AACM has provided a platform for Black working class composers and musicians from the south side of Chicago, transforming the musical landscape in the process. By pioneering new forms of composition and improvisation, and fighting for their place in the wider world of experimental new music, the AACM’s members have broken down the racist and classist barriers artificially separating jazz and classical composition. They’ve also engaged fruitfully with Black popular music, from blues, funk and reggae to hip hop and house. And through George E. Lewis – the first African American composer to be invited to IRCAM in Paris – the AACM has also been at the forefront of computer music. The AACM embodies a liberated future where there are no limits on creativity. Its influence is vast, from European free improvisation to Afro-Futurism, Chicago post rock to the 21st century Brooklyn avant-garde.

The AACM was founded in 1965 by Muhal Richard Abrams, Jodie Christian, Steve McCall and Phil Cohran. Its charter committed the organisation to “nurturing, performing, and recording serious, original music.” In calling themselves “creative musicians,” the AACM’s members rejected genre, refusing to be bound by expectations of what a black so-called “jazz” musician should be. They wanted to be taken seriously as composers, but their jazz backgrounds allowed them to recognise that composition doesn’t start and end on the page. Whether working with traditional notation or graphic scores, AACM composers created frameworks for creativity, showing that composition and improvisation are two sides of the same coin. Furthermore, this democratic approach challenges the hierarchy of composer-conductor-musician. As Anthony Braxton wrote in his For Trio (1978) liner notes, “as is always the case with creative music, the actual creativity is an affirmation and testament to all the people participating.”

There’s no AACM “sound” as such. Members were encouraged to explore unconventional instrumentation, extended techniques and graphic notation. Extra-musical elements were embraced: poetry, dance, visual art. The nurturing of creative musicians goes hand in hand with a strong commitment to social justice, community organizing and education. Through formal instruction, community ensembles and jam sessions, the AACM has nurtured several generations of creative musicians.

To reel off the names of some key members is to travel the spaceways of post-war musical genius: Muhal Richard Abrams, Roscoe Mitchell, Henry Threadgill, Anthony Braxton, Amina Claudine Myers, Jack DeJohnette, Wadada Leo Smith, Lester Bowie, Joseph Jarman, Fred Anderson, George E. Lewis, Douglas Ewart, Mwata Bowden, Nicole Mitchell, Tomeka Reid, Jeff Parker, Matana Roberts, Ben LaMar Gay, JoVia Armstrong. While celebrating these great individuals, we should also recognise the power of the collective. As Art Ensemble Of Chicago percussionist Famoudou Don Moye put it, the AACM is a power stronger than itself.

In his excellent new book, Sound Experiments: The Music Of The AACM, Paul Steinbeck argues that the AACM founders’ dream of carving out a space for African American composers in the realm of experimental music was finally realized in 2016, when Henry Threadgill was awarded the Pulitzer Prize For Music. The Pulitzer has historically been slow to recognise the achievements of African-American composers. In 1966, its committee vetoed the nomination of Duke Ellington, a scandalous act of racist gatekeeping. Today, there is still resistance to the decolonising of classical music, not least from right-wing culture warriors hell bent on upholding the supremacy of the Western tradition. But there are positive signs of change, with AACM composers leading the charge. Last year’s BBC Proms featured Lewis’ Minds In Flux, a stunning piece for orchestra and interactive electronics. Thanks to the groundwork of Threadgill, Lewis, Braxton, Mitchell and others, younger non-AACM composers like Tyshawn Sorey can occupy those spaces too.

Anthony Braxton

EFG London Jazz Festival’s double headliner from Threadgill and Braxton at the Barbican further affirms their status. It’s the first time Threadgill has performed in the UK for over a decade, and while Braxton has visited these shores more regularly, this is the first outing of his New Quartet, an international ensemble featuring the brilliant Portuguese trumpeter Susana Santos Silva, Italian bassist Carl Testa, and Brazilian drummer Mariá Portugal. As journalist and broadcaster Kevin Le Gendre points out in his introduction, Braxton’s music can be experienced in numerous contexts, from orchestra to opera, large ensembles to solo.

The last time I saw Braxton was in Berlin in 2019, where he performed Sonic Genome, a six hour sound environment featuring 60 musicians. Between orchestral set pieces, the musicians would wander off to form smaller groupings, interpreting scores from Braxton’s “Ghost Trance” series. The audience members, or “friendly experiencers” as Braxton puts it, could choose their own adventure, following one group before moving on to another, or finding a spot to soak up the sound clash from the different ensembles moving around the space. In the final hour, Braxton strolled into the atrium, forming an impromptu trio with another saxophonist and a bassist. As their improvisation came to an end, the building reverberated to the sustained tones of the entire ensemble moving around the space, as if the walls themselves were singing. It remains one of the greatest musical experiences of my life, profoundly moving yet tremendous fun.

Braxton’s main small group projects of the past few years have been ZIM, in which Tomeka Reid, Brandee Younger, Taylor Ho Bynum and other young masters negotiate a new compositional system, and a Standards Quartet with British musicians Alexander Hawkins, Neil Charles and Stephen Davis. The New Quartet sits somewhere between them. The music is carefully composed, with the musicians following Braxton’s score and gestural cues. And while there are only fleeting glances of the conventional jazz language explored in the Standards Quartet, the musicians’ improvisational sensibility is key to teasing open the structures. There are several fully formed passages, from the stately opening saxophone melody and trumpet counterpoint to the closing insect march. Sputtering exchanges flow into disarmingly graceful melodies.

At certain points, the musicians clearly articulate Braxton’s language types, the musical elements which form the basis of his improvisations: a trill, a held tone, a staccato burst. Each musician brings their own character to the music: independent voices within a codependent structure. Santos Silva’s silvery tone and susurrant mouthpiece effects complement Braxton’s fluid, lyrical tone, while Portugal’s intuitive phrasing and use of shakers on the drum skins bring a slightly ramshackle quality to the stop-start rhythms. Testa offers solid support on bass, stepping forward for the occasional fleet fingered solo. From a laptop and mixer, Braxton folds keening sine waves and bubbling synth tones into the texture. This fifth element is subtle, but certainly not superfluous. The overall effect is to create an otherworldly electro-acoustic atmosphere, but at certain points, the AI intervenes, setting off a rising harmonic tone against Silva’s tremulous lines.

Henry Threadgill

The ZIM Ensemble I saw at London’s Café Oto in 2018 approached Braxton’s compositions with a freeness that comes from sustained engagement with musical language. The New Quartet isn’t quite there yet, but this debut performance feels like the start of an exciting new chapter in Braxton’s music. It’s exciting to see these wonderful artists getting to grips with the music, fully embodying the role of creative musician. For Braxton himself it’s a learning process. During one trio section, he pencils in changes to the score, presumably reshaping the music in response to what has come before. Braxton is all too often mischaracterised as cerebral, a robot, yet in moments like this his intuition and playfulness come through beautifully.

Zooid has been Threadgill’s primary ensemble for over a decade. Currently a quintet, it features Threadgill on saxophone and flutes, Liberty Ellman on acoustic guitar, Jose Davila on tuba and trombone, Christopher Hoffman on cello, and Elliot Kavee on drums. Their fluency in the language and heightened level of interaction results in music that is mind-boggling in its intricacy, yet also graceful, even funky in places. It’s certainly possible to draw line from Zooid to Threadgill’s earlier projects: the flowing polyharmonic lines and elastic rhythms of Air, the unconventional instrumentation of Very Very Circus, the knotty strings of Makin’ A Move. Yet it’s very much its own project, one people will be trying to get their heads around for years to come.

As Threadgill’s producer Yulun Wang told me in 2019, “The whole idea of Zooid is to invent a new form of group interaction. Essentially, he asks each musician to play on and improvise along a system of prescribed intervals. To my ears it is a way for Henry to enforce counterpoint [and] make sure that everybody is interlocking yet doing their own thing. And that’s why you’ll never hear another band that sounds anything like it.”

So what does it sound like? And what the hell is going on? For all the intense concentration required of the musicians, they never come across as studious. During the lengthy first stretch, the group plays with restrained volume and attack, yet there’s a huge amount going on. Ellman and Hoffman absolutely shred it, their labyrinthine lines and chordal vamps somehow intertwined yet independent. Davila’s tuba ostensibly plays the bass role, and while his motifs help anchor the music, he is free to roam the instrument’s upper range. Combined with Kavee’s painterly touch on the kit – there’s one section where he plays nothing but cymbals – it gives the music a lightness and clarity of form that is quite remarkable. It can take a while to tune in, but Threadgill rewards us in the final section with a luminous alto saxophone lead, its melodicism lifted by an understated swing. This is my first time seeing Threadgill. As it should be, it’s left me with as many questions as answers.

The previous night, the Barbican played host to CHICAGO X LONDON, featuring a younger generation of musicians from both cities. The trans-idiomatic reveries of Angel Bat Dawid and Ben LaMar Gray take the AACM forward. But despite their elder status, Braxton and Threadgill remain at the cutting edge. Next level creativity, from ancient to the future.