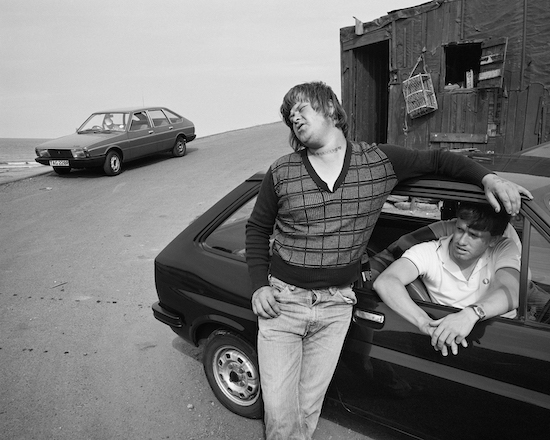

Bever, Skinningrove, N. Yorkshire, 1983 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

Aged 17, Chris Killip was excitedly flicking through Paris Match’s coverage of The Tour De France when he stumbled upon Henri Cartier-Bresson’s photograph, Rue-Mouffetard, Paris, of a small boy carrying two bottles of wine. This proved a profoundly touching experience for Killip, who immediately told his father that he wanted to be a photographer. He soon spent a summer photographing a local beach, earnt enough to move to London and eventually landed a job as Adrian Flowers’ assistant.

After a visit in 1969 to the MOMA and an encounter with their permanent collection – including the likes of Paul Strand, August Sander and Walker Evans – Killip’s motivations changed and he began to focus on social documentary photography, returning back home to the Isle of Man to start capturing the agricultural community of the island whilst working in his father’s pub.

A series of evocative portraits from this period depicting the creeping eradication of the traditional peasant culture of the Manx opens the exhibition. They attest to a change of pace from the photographer’s days working in London, developing the early stages of his unique style grounded in the traditions of those whose work he came across in New York. Killip was taking photographs for their own sake and working on his own time, patiently documenting those at risk of erasure.

Although born on the Isle of Man, Killip developed a lifelong attachment to the North-East after first driving through the region on a tour of England. Drawn to the industrial landscape and its working-class communities, he applied for a fellowship with the Northern Gas Board photographing a new gas pipeline being laid near Newcastle, which also gave him the opportunity to document these areas in his spare time.

In a 2020 Interview for the Martin Parr Foundation, Killip told the photographer that his eye was drawn to the proximity of industry to rural areas and the confounding of time through a strong connection to their agrarian past, something which he felt he could relate to from his childhood. His extensive archive of the North-East makes up the majority of the show. The more well-known images of the vernacular landscape appeared in the book, In Flagrante, widely considered to be his masterpiece, containing some of the most important British photography of the twentieth century.

Cookie in the snow, Seacoal Camp, Lynemouth, Northumbria, 1984 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

Included in the landmark publication were a number of photographs from Seacoal beach in Lynemouth, where Killip frequently visited and lived from 1982–83. The show contains previously unexhibited work from this series, capturing the beauty of workers battling against the fierce sea, looking for coal on the shore in the shadow of a coal-burning facility. The intimacy of the series is testament to Killip’s perseverance. It took him several years and a moment of serendipity to be accepted by the closed community. He stayed in touch with them up until his death in 2020. Seacoal would later be re-landscaped and cleared away, the communities imprint on history all but invisible on the landscape, yet immortalised in Killip’s pictures.

During the 70s, there was a wave of photography collectives and cooperatives in the UK intent on confronting the traditional imbalance between the photographer and subject. In the North-East, this was particularly driven by the Side Gallery in Newcastle where Killip was director from 1977–79. Two other affiliates of the gallery, Sirkka-Lisa Konttinen and Tish Murtha, were recently included alongside Killip in Tate Britain’s exhibition After Industry: Communities in Northern England 1960s–1980s, an overdue showcase by a major art institution of important work from this time.

Girls Playing in the street, Wallsend, Tyneside,1976 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

In line with the philosophy of this movement, Killip believed it was essential to embed yourself into a community to fully embrace their complexities and contradictions. He saw his archive as something belonging to the people depicted. As co-curator Ken Grant told The British Journal of Photography, “his commitment to both the region and communities he photographed is singular in the medium”. Killip memorably ended In Flagrante with the quote, “The photographs tell you more about me than what they describe. The book is a fiction about metaphor”.

Using a stationary method, Killip would pensively wait for hours on end for a moment to capture, after setting up his cumbersome 4×5 camera. This patience is evident within the Skinningrove series, a poignant essay on a tight-knit fishing community in the North-East, where time often feels suspended and subjects gaze into the misty distance, their eyes never seeming to notice Killip’s lens.

A running theme throughout Skinningrove is Killip’s friendship with a local fisherman named Leso. Tragically, Leso later died in an accident on the water with his friend David and the series includes a sensitive, affecting photograph of his young son grieving on the water, illuminated by the diffused light of the horizon captured by a long exposure. David’s mother asked Killip for the photographs he’d captured of her son throughout his life and he gave her an album of prints, reiterating how significant photographs can be for communities during times of loss. Killip later reflected that this alone had been enough of a reason to document the small village. “It’s true that photography is a witness,” said Roland Barthes in 1977,“but a witness of what is no more,”

Unidentified man and Brian Laidler, Seacoal Beach, Lynemouth, January, 1984 © Chris Killip Photography Trust/Magnum Photos

There are two other series gathered in The Photographers’ Gallery’s retrospective, both dealing with major social movements under Thatcherism. The first, titled The Station after a DIY Anarcho-punk venue in Gateshead, depicts young, spirited punks. Hallmarks of the subculture are evident throughout the exhibition (notably in Skinningrove), as angst and disaffection swept over the UK. The second is a series of powerful images of the Miners’ Strike which Killip documented in its entirety (fifty-one weeks) culminating in his most overtly political work. A striking miner dressed as a policeman with a pig’s mask on and framed by a placard reading “Victory To The Miners” needs little decoding. In 2020, the photographer donated some of these prints to the Archive of Modern Conflict, as he believed this was how the event should be viewed historically.

Although Killip rejected the notion that his work was emblematic of the Thatcher years, with hindsight it’s difficult not to be influenced by knowledge of the socio-political context. Looking at Chris Killip’s documentation of industrial decline, you are reminded of the human element economic deprivation, as well as the resilience of the communities that were most affected. The North-East’s scars are still visible today as empty promises about ‘levelling-up’ predictably fail to materialise – often only exacerbating existing inequalities. In Killip’s own words, “history is most often written from a distance, and rarely from the viewpoint of those who endured it.”

Chris Killip: 1946–2020 is at The Photographers’ Gallery until February 2023