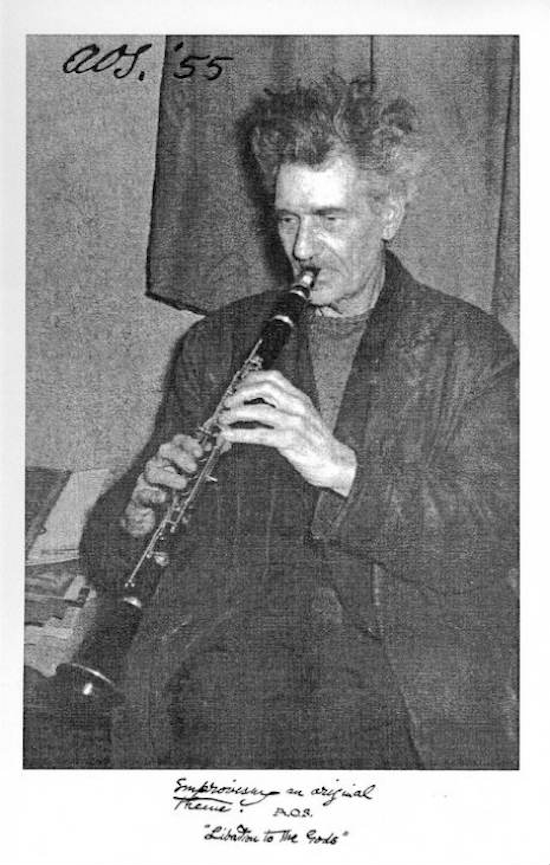

There’s a 1955 photograph of the South London mystic and artist Austin Osman Spare, in the last years of his life, playing the clarinet, his hair on end, looking like a wild jazz musician. "Improvising an original theme," reads a caption in Spare’s own scratchy hand, "Libertine of the Gods".

While Spare was hardly a libertine, he was undoubtedly an improviser and experimenter, developing styles and techniques to create a visual aesthetic that, while broader than many people realise, was always his own. He was also a tinkerer with a fascination for radios, which he built for himself and for friends – a hobby popular with men in the 1920s and 30s. Visitors noted that his flats were always littered with exotic totems, tribal art and radio parts, and he regularly painted work onto wooden radio set panels and speaker cabinets (as in the piece illustrated here, sold at Bonhams Auction House in 2015).

Spare was of course, also an occultist – perhaps primarily so. He communicated regularly with the spirit world, and explored it in trance states, encountering human, non-human and approaching-human entities. For Spare, radio, and the waves that carried the music he loved to listen to, were more than just a metaphor for the spirit world. They were an active mode of conveyance for occult energies and vibrations – the swirling, ectoplasmic tendrils from which odd figures emerge in some of his most dense and haunting work.

As a painter and draftsman he worked fast, and constantly, producing hundreds of artworks from his teenage years to his death in 1956, aged 69. Ranging from the exquisitely fine to the manically grotesque, his work sometimes incorporated ornate, yet compact, magical alphabets that appear, at first glance, to be asemic, but actually collapse meaning into striking idiographic sigils that would look right at home on any number of black metal albums – and undoubtedly informed many.

Spare’s combination of irreducible, yet charismatic, strangeness, prodigious artistic talent, satisfyingly enigmatic writing, and his status as a true cultural and social outsider – as well as the somewhat tragic circumstances of his life and death – have made him a highly-appealing figure for artists, occultists and musicians. It also helped that, until relatively recently, original artworks were available for – in art world terms at least – extremely reasonable prices.

In 2011 we at Strange Attractor Press published the first full biography of Spare, by Phil Baker (due a reprint soon), and in 2016 we revealed Jonathan Allen’s Lost Envoy, reproducing a hitherto unknown tarot deck created by Spare in around 1906, discovered by Jonathan in The Magic Circle Museum archives. We’re now approaching the end of a successful Kickstarter campaign to raise funds to recreate Spare’s tarot as a scale facsimile deck, and also to publish a significantly expanded edition of Lost Envoy.

To celebrate this, we thought we’d compile a brief, no-doubt-incomplete, playlist of songs and music that draw inspiration from Spare and his work.

Bulldog Breed – ‘Austin Osman Spare’ (1969)

The first musical tribute to Spare is this enjoyably flouncy psych number released by Decca in 1969. It captures the spirit of the period’s flourishing occult revival, while being a few years ahead of the curve in recognising Spare as a significant magical figure. Esotericists and collectors of recherché art were aware of Spare at this time, but his name wouldn’t reach the wider scene for a few more years.

The song’s origins are pleasingly mundane: Spare was an acquaintance of guitarist Rod Harrison’s grandmother in South London. She and his aunt had a number of Spare artworks around the house, which Harrison inherited, then lost, having done a runner after failing to pay his rent on a flat.

Led Zeppelin – ‘Black Dog’ (1971)

Jimmy Page infamously invested heavily, both psychically and financially, in the occult revival, setting up a magical publishing imprint, Equinox, and opening a shop of the same name off London’s Kensington High Street. He would likely have come across Spare’s work as part of his fascination for Aleister Crowley – the Great Beast and Spare came into each others’ magickal orbits around the time Spare was working on his tarot, but didn’t get on – or perhaps at one of his posthumous gallery appearances, maybe Victor Arwas in Mayfair. Page was an avid Spare collector at one time, and still owns some iconic works.

It’s been suggested that the sigilisation of Led Zep’s players’ names on the cover of IV was inspired by Spare’s technique. "Zoso", Page’s name, also incorporates ‘Zos’, a magical name Spare used in his writing to refer to the idea of the physical body and, later, also to himself. It’s tricky to select a song from such a colossal musical landmass, but I like to think Spare might have enjoyed ‘Black Dog’, with its raw, atavistic emotional energy and a potentially supernatural reference in its title. But he may just as likely have been quite puzzled by it, and indeed all of the music in this selection.

Amebix – ‘No Gods No Masters’ (1984)

West country crust rockers Amebix adopted a late Spare artwork, sometimes titled ‘The Vampires Are Coming’, for their logo, which now adorns patches, T-shirts and bootleg covers. The image would have been widely seen on the cover of the first issue of Man Myth And Magic ("The Most Unusual Magazine Ever Published!"), a popular partwork first published in 1970. It also appeared in TV advertising for the series, luring many impressionable young minds into the dark arts.

Kenneth Grant, one of Man Myth And Magic‘s editors, was a close friend, supporter and promoter of Spare in the last years of his life, and for decades afterwards, until his own death in 2011. Grant wrote several books of dense magical lore which, for occultists of the 1970s and 80s – including many of the musicians featured here – forged a path of discovery towards Spare’s magic and art.

Psychic TV – ‘Thee Starlit Mire’ (1988)

Throbbing Gristle, the band that launched a thousand noise acts, played a significant role in the occulturisation of the musical underground (though probably less of one than Led Zeppelin!). But it was the post-TG groups – Psychic TV and its splinter cells Coil and Current 93 – who really pushed things to the next initiatory level: magical language, imagery and practice appearing as central to their music, style and philosophy.

This track’s pullulating, rhythmic intensity echoes some of Spare’s darker images and is drawn from Psychic TV’s 1988 album Allegory And Self, which featured a Spare image, ‘Fashion’, from A Book Of Satyrs on its cover, and several more in an accompanying booklet. The title is borrowed from a 1911 book of aphorisms by two doctors, James Bertram & F. Russell, illustrated by Spare, which PTV-associates Temple Press also republished in a beautiful edition.

Fields Of The Nephilim – ‘Psychonaut’ (1989)

Stevenage’s finest steeped themselves in occult lore and imagery, including Austin Spare’s art and magic. Psychonaut borrows its title from one of the foundational texts of chaos magic, published by Peter Carroll in 1982. Psychonaut, and the earlier Liber Null (1978), placed a reading of Spare’s rather opaque magical philosophy and practice as central pillars in its then-radical new approach to the magical arts. (A later Fields Of The Nephilim live album would be named after a Spare book, Earth:Inferno.)

Richard Stanley’s striking video – at times reminiscent of both Kenneth Anger and Benjamin Christensen’s1922 Häxan – depicts someone undergoing the Native American Sun Dance ceremony, a bloody practice intended to induce out-of-body states, made famous by the 1970 Western A Man Called Horse. (The Nephilim drew heavily upon spaghetti western trappings, as well as occult imagery). Imported via extreme American body artists like Fakir Musafar, the Sun Dance was, around this time, finding its way into performative SM cultures, making this video a perfect time capsule of the bloody edge of the late 80s underground.

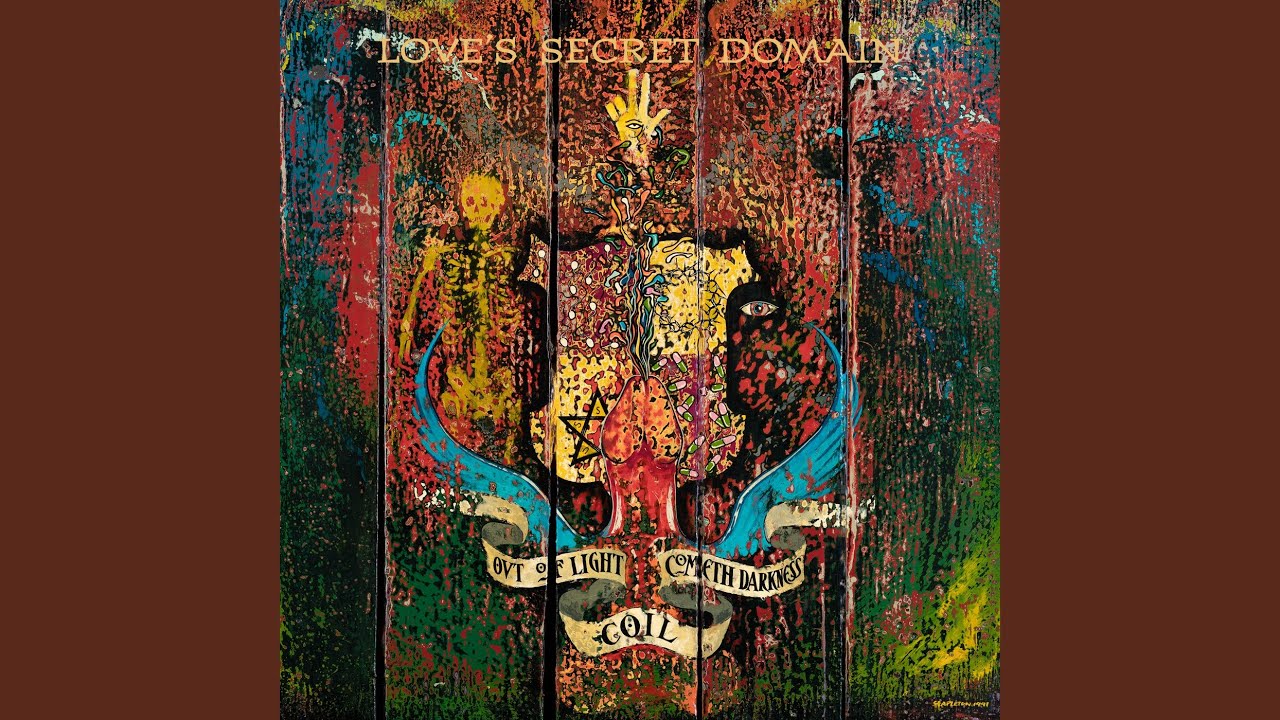

Coil – ‘Titan Arch’ (1991)

Coil’s John Balance spoke of his close connection to Spare, at times claiming to be in contact with his spirit, and owned a large collection of his art, some of which appeared in their later live performances. In Coil’s formative years the teenaged Balance was also a member of experimental performance group Zos Kia – a name drawn directly from Spare’s esoteric writings – with fellow early Psychic TV member John Gosling.

Coil later coined the term "Sidereal Sound’ to describe some of their disorientating audio-processing techniques, a phrase borrowed from Spare, who referred to his warped portraits of film stars as sidereal – a play on the fact that they were "stars" (sidereal is an astronomical term), and appeared as if drawn from the cheaper "side" seats of a cinema.

Although Spare was a major figure in Coil’s personal pantheon, their music didn’t draw explicitly on his writing, though this fine track, featuring Marc Almond on vocals, conjures distinctly Sparean imagery with lyrics adapted from Kenneth Grant’s book Outside The Circles Of Time (1980).

John Zorn – ‘Ode V’ (2011)

The album The Satyr’s Play / Cerberus, a particularly gnomic release on Zorn’s Tzadik label, was illustrated with several Spare drawings (66 copies were hand-bound in black goat skin for added occult flavour). Zorn’s deep interest in magical history and practice has resulted in albums inspired by kabbala, gnosticism and the magic of Aleister Crowley. Zorn also edited and published five editions of Arcana a journal dedicated to esoteric writings about music.

Cyclobe – ‘Tarot’ (2012)

Derek Jarman had a keen, early interest in Spare as both an English Surrealist and a magician. This is one of three pieces commissioned, posthumously, from Cyclobe as soundtracks to some of his early shorts – Tarot from 1972, Sulphur and Garden.

Cyclobe’s Stephen Thrower was a friend of Jarman’s, and appears in his The Last of England (1987), while Ossian Brown is a Spare collector. In their archive is a copy of Spare’s The Book of Pleasure (1913), originally given to Coil’s John Balance by Jarman, who was a close friend and associate of Throbbing Gristle, Coil and Psychic TV.

Psychedelic whimsy, rock bombast, gothic psychodrama, avant-jazz and the experimental sublime: that Spare can have inspired musicians working in so many distinct styles reflects his own versatility as an artist and, perhaps, the broadly appealing – if necessarily opaque – nature of his ideas as a canvas for the imagination.

If you’d like to pledge towards our Austin Spare tarot deck set, you can do so here

Kickstarter pledgers will receive unique books, ephemera and other items.