I’ve spent the last nine years on and off the road with my band Big Joanie. I’ve sat for so long in a cramped van that the sensation of tumbling out at the venue with numb, tingling legs is all-too-familiar. I’ve stood in front of unresponsive crowds who send us into a pit of despair. I’ve been offered little more sustenance than a few cans of beer, packet of crisps, and a smile from uncaring promoters. It’s far from the popular perception of touring being glamorous – leaving your hometown and travelling the world, crowds of wide-eyed devotees screaming your name and affirming the validity of your art. From years of personal experience, I can tell you that there’s a grimy and mundane reality to moving from town to town every day.

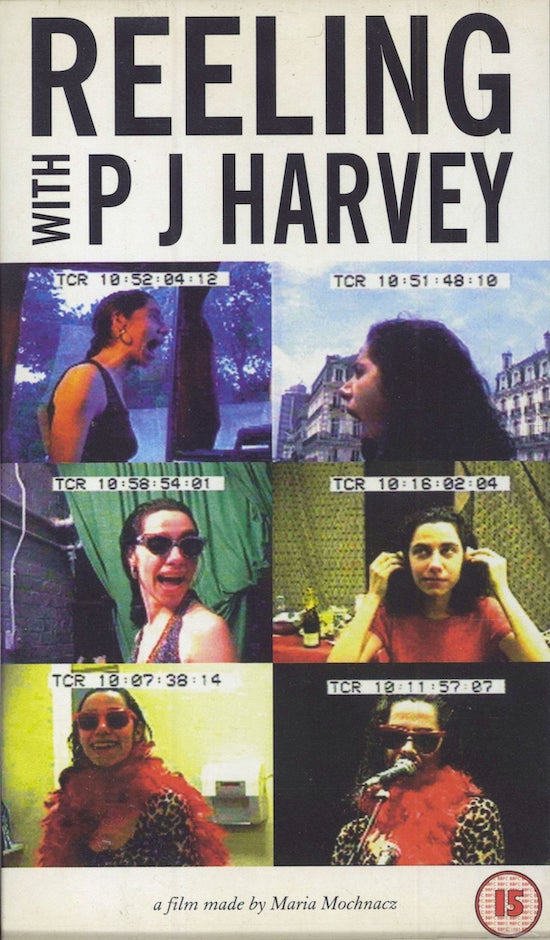

Yet touring is often where musicians feel most at home, which is why they often try to capture it in a documentary film – an attempt to share their ‘real’ selves with the world. I’ve been addicted to music and tour docs since I was a teenage music nerd ordering DVDs online, but one that has continued to hold my fascination for over a decade is the 1994 film, Reeling With PJ Harvey, or Reeling, as it is more commonly known. The film was directed by photographer and filmmaker Maria Mochnacz, who for over two decades was Harvey’s main collaborator on her album artwork and music videos. When the pair met Harvey was 18 and played in the band Automatic Dlamini with Mochnacz’s then boyfriend John Parish (who also became a long-time Harvey collaborator). Though Mochnacz was a few years older than Harvey, the two bonded over their shared interest in art. When Harvey needed press images after signing to the independent label Too Pure in 1992, Mochnacz was the first person she called, mainly because she was the only person she knew with a camera. The same logic followed when Harvey needed a video for her single ‘Dress’. Despite having little experience, Mochnacz got stuck in. She went on to create some of Harvey’s most memorable music videos, including ‘Down By The Water’, ‘Send His Love To Me’ and ‘50ft Queenie’.

Reeling was filmed over a three-week span during Harvey’s 1993 European and American tour. It includes live footage from two dates at The Forum in London, and two music videos; ‘50ft Queenie’ and ‘Man-Size’. Mochnacz brought in Peter ‘Pink’ Fowler, co-founder of the late 80s, no frills cult music show Snub TV, as an assistant, as she felt she could not do the live filming justice by herself. Filled with backstage banter and rare performance footage set against the backdrop of the dull interiors of 90s music venues, the film offers a rare insight into the world of Polly Jean Harvey at the start of her career.

I have watched Reeling more times that I can recall. I first fell in love with Harvey in my teens around the time of her 2004 album Uh Huh Her and was drawn in by honesty and frank interpretations of love, lust, and life. For some reason sitting in my teenage bedroom with no boyfriend or even crush to speak of, listening to a woman singing about becoming so infatuated with a man that she’d cut off his legs made sense to me – I’m a romantic, what can I say? As a teenager with too much time on my hands I spent evenings after school trying to find old interviews and press photos, or waiting ten minutes to stream a two-minute music video in the early days of YouTube. One fateful day when I was looking for ways to waste money on eBay I found a VHS copy of Reeling.

When it arrived in the post a few weeks later I rushed upstairs to my bedroom, put the tape into the VHS machine of my clunky 15-inch metallic blue Argos TV and pressed play. As someone who dreamed of one day playing in a band too, I liv…