أحمد [Ahmed] photographed by Guy Bolongaro

Seymour Wright is a saxophonist living in London. His work is about the creative, situated friction of learning, ideas, people, and the saxophone – music, history and technique – actual and potential. Seymour’s solo music is documented on three widely-acclaimed collections – Seymour Wright of Derby (2008), Seymour Writes Back (2015) and Is This Right? (2017). Some of his current collaborative projects are: @xcrswx with Crystabel Riley; أحمد [Ahmed], with Antonin Gerbal, Joel Grip and Pat Thomas; GUO with Daniel Blumberg; XT with Paul Abbott; and, the RP Boo Trio; he is also a founding member of The Creaking Breeze Ensemble.

“They are asking who Ahmed is,” she said over the phone in 2019. “They need to know more about the transaction before they can release the funds. Can you tell me who he is?”

“I’ll confess,” Edward George said. “I didn’t know who Ahmed was, in, or out of, parentheses”

I am talking (speculating) about أحمد [Ahmed], a group, along with drummer Antonin Gerbal, double-bassist Joel Grip and pianist Pat Thomas, in which I play alto saxophone. [Ahmed] make improvised music. We think about it and prepare it independently, in our different, remote lives, worlds and ways, but then come together to ‘realise’ it in occasional performances. This unfolds and grows out of the ‘tradition’ of ‘European improvised’ (‘non-idiomatic’/‘meta’) music. The improvised structures of what we do are the consensus of our shared doing. What emerges when we play is much bigger than the four of us, the ideas, energy, techniques and emotions that we put in, and any listeners or audiences that we find ourselves together with in sound or space. It acts back upon and transforms all of us each time we ‘play’. And so, we learn and are enriched by this investigation. The product, the music, is the investigation – [Ahmed] making/using ‘music as a medium of thought’ in Edward George’s words.

At the same time, we humbly and carefully explore, investigate, and re-imagine the music and ideas of Ahmed Abdul-Malik. This unfolds, grows out of, and locates us in, the ‘tradition’ of jazz music, and through this many different cultures, and ancient human traditions of music, ritual and thought. For me, the careful humility is vital to stress here. I am a white, London-based saxophonist working in the 21st century with colleagues of different backgrounds at the margins of what is (to many) acceptable in terms of music, genre, technique, interpretation, history and ‘tradition’. Carefully, and with humility, we need to ask questions now about the past and future, and be willing, in dialogue together, to venture and probe the awkward wealth of this investigation.

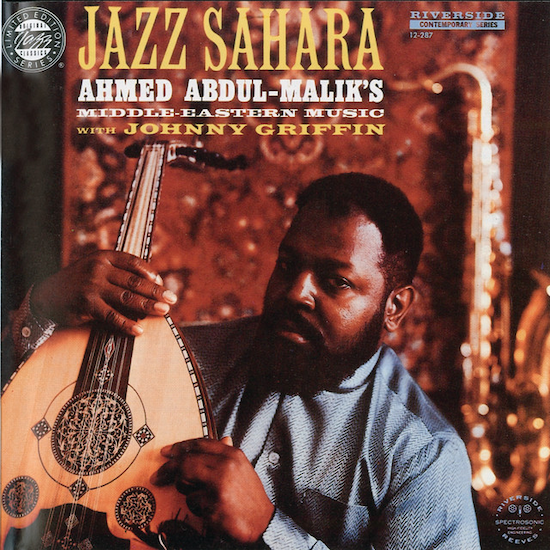

Abdul-Malik was a visionary bassist, oudist, composer, and educator. Born in Brooklyn to Caribbean parents, he converted to Islam at some point in the 1940s. In the 1950s he worked in the groups of Thelonious Monk, John Coltrane, Randy Weston and Cecil Taylor. He also led his own bands, making five remarkable LPs under his own name that situated, imagined and developed an incredible, unique (and awkward) synthesis of Islamic, West and East African, and Caribbean music into jazz; new ideas, modalities, rhythms, voicings and instrumentations. Or, as Abdul-Malik no doubt knew, that situated, imagined and developed this back into ‘jazz’, as a convergence of histories, a reframing, celebrating and surfacing of ingredients, components and substances that were there from before the ‘beginning’.

“There is”, as Abdul-Malik told Bill Coss in a 1963 Down Beat interview, “a difference between a B flat and an A sharp – but not on the piano. The piano limits you. There are no one-eighth or one-quarter tones available. People like Monk should have them”.

There is a difference between the word ahad and the word wahid in Arabic, but not in English, in which both translate as ‘one’. Both ‘ones’ are sides of [Ahmed]’s most recent record – a 7” single called ‘AHAD/WAHID’. And both of these ‘ones’ are excerpts from two live, spontaneous, collective re-arrangements and re-imaginings that we did of Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s composition ‘El Haris (Anxious)’ – a piece that first appeared on his 1958 debut LP Jazz Sahara.

One of these ones, ‘WAHID (45rpm)’ – was recorded at [Ahmed]’s first London concert at Cafe OTO, on September 6, 2017. It’s a section cut from about 10 minutes into the first of the two sets we did that night. That concert celebrated the launch of the first [Ahmed] LP New Jazz Imagination. It was, in fact, the third opportunity we had had to play together. The second time we’d played (which was our first concert) had been in Sweden to a joyous, rammed converted barn at the wonderful Hagen Festen at Dala Floda on August 6th 2016. The music from that concert eventually became New Jazz Imagination. In 2017 we asked Robert Levin to write the liner notes for this first LP.

Sixty years previous Levin had written the liner notes for John Coltrane’s 1958 LP Blue Train. The year before that, Coltrane had worked extensively with Abdul-Malik in Thelonious Monk’s quartet. Five years later, in 1963, Levin wrote the liner notes for an LP titled Reflectivity by the Walt Dickerson quartet, on which Abdul-Malik played bass. For those notes Dickerson (who plays vibraphone) spoke to Levin and explained how, on a vibraphone and bass duet called ’The Unknown’), he “set[s] up a tonal basis for Malik to probe into the unknown as he sees it. That seems to me to be where most of the answers must be in all endeavours and spheres. Music must go in this direction.” (The italics are mine)

The ‘experimental’ in experimental music certainly can be about uncovering and treasuring the unknown. This was what Abdul-Malik was doing, and, exactly where, and how [Ahmed] started. Again, music as a medium of thought.

This is something I’ve long been into. I wrote in a 2011 liner note, that “everywhere the orthodox systems of our times anticipate the careful and clear presentation of ready-worked-out, on-tap outcomes, throughout our lives. Said systems seldom afford focused vantage on the vagaries, protean problems, the awkward wealth, of investigation itself. Generally, the on-goings of development are hidden, edited or simply unseen; what has been developed over time is rendered public, honed for appreciation after the fact, variously knowable, reproducible, and endorse-able qua final product.”

The italics are mine now in 2022, because it’s an idea important to stress. One version of creative practice is the working out, looking into a matter deeply, finding pleasure (and treasure) in searching for the hidden, secret, and mysterious. This looking into a matter deeply is (or at least, can be) the product. And it’s this awkward wealth, the friction of investigation, that I want to explore a bit here, to ask how this can work in sound but through trying to do a version of it here in words.

The very first time [Ahmed] played was November 8, 2014 (again in London) at a night club in the daytime. In private, an afternoon of prob[ing] into the unknown as we saw it. Implicitly that was the direction in which we went. ‘El Haris (Anxious)’ and ‘Is’ma (Listen)’ were the two tunes we’d decided (by email) to try – but we hadn’t discussed how we’d try them. And that afternoon was the first time that the four of us stepped from the words of the idea of ‘playing the music of Ahmed Abdul-Malik’ – whatever that might be – into the idea as act. A shift in the imaginary gears to probe into the unknown as [we] see it. It marked a convergence of our respective histories: Pat had met Joel and Antonin in Paris in 2013, and they’d begun to work as a trio – اسم [Ism]; I’d also met Joel in Ljubljana, and Antonin a bit earlier in Paris that same year; and though I’d known Pat for two decades we’d never played music together (or had a context to). I’m not sure that any of us knew either the ‘unknown’ or ‘B flat and A sharp’ quotes that November day. But Abdul-Malik’s work – his bass and oud playing, philosophy, imagination and vision, his own radical LPs, and his presence on so many crucial, cuspid records – had long been a source of overlapping (different) fascination, inspiration and mystery to all four of us. Its complex resonance was important: its allusions and elegant synthesis and investigative, interrogative asking of questions stretching forward into future music and back into history. The prospect was compelling enough to bring us into a shared space of imagination – a context, reason and focus for our shared imaginations, actuals and potentials.

After suggesting (back in the Relativity LP liner notes) to Robert Levin that ‘music must go in this direction [of probing into the unknown]’, Walt Dickerson adds: “Of course, the controlling interests make it, economically, very difficult for an artist to probe.”

“If you could get out of economic problems,” Abdul-Malik echoed to Bill Coss (back in Down Beat) in 1963, “you could find the time, the energy to create. You have to have some peace of mind to create. The lack of this has brought about a serious problem. As the environment has changed in the last 10 years, many musicians have begun to believe that they will not be accepted if they venture. They are wrong to let that stop them, but I can understand that because there really is no place for them to show development.”

This probing, venturing work – and the physical, conceptual, and economic spaces it needs (and lacks) – is crucial to what I want to say here. It is at the heart of a radical, experimental and political practice of investigating, questioning the orthodox systems of our times, the ready-worked-out, the on-tap outcomes, the models. The way things, the past (and the future) are already ‘supposed’ to be. Abdul-Malik imagined ways to question this. Our work with [Ahmed] is about making space for this investigation, too. And this is one sense in which we develop Abdul-Malik’s own work – through the (re-)imagining and (re-)interpretation integral to investigation. Asking questions, looking deeply into matters, like: why is Abdul-Malik not better known? How can we completely improvise a ‘blues’? How do ideas and influence move? The open optimism of such questions, the potential, the prospect of asking, and possible responses, are something rich. And the inspiring energy of this stretches both back and ahead – at once memory and promise.

Abdul-Malik’s probing into the unknown, his ‘approach to Oriental music’ wrote Dan Morgenstern in his 1963 sleeve notes to The Eastern Moods of Ahmed Abdul-Malik, “is not that of the scholarly ethnologist concerned with reconstruction and “authenticity” – a concern which too often bogs down in academicism and results in pale, lifeless reflections of its models. Thus, he has sometimes had to suffer the criticism of self-styled musicologists on the one hand, and narrowminded jazz musicians on the other. “These people would say that I was playing things out of place, and that I couldn’t discipline myself.” They missed the point, for Ahmed’s music is interpretive and original, and must be judged on its own terms and not through comparisons.”

He was synthesising and imagining fusions of traditions and practices. So are we. In different ways, but inspired in this experimental practice by him. Our new space is overlapping into his older space. From the start we imagined the music of Ahmed Abdul-Malik as a process of investigating a history of jazz that has been missed, or overlooked, or ignored, or blocked (or hidden, even). The anonymous liner note to his 1960 East Meets West LP says: “Abdul-Malik believes that [… traditional music that is common in varying degrees, to North Africa, Egypt, the Sudan, Syria, Jordan, Iraq and Lebanon. There are also occasional traces of West African influence …] exerted a greater pre-jazz influence than is generally recognized. He notes that many different cultures – not just the usually cited Congo and West African – were represented in the initial African contribution to American music.”

Pat has been exploring, researching, writing about and playing this idea for most of this century. For example, his liner notes to [Ahmed]’s third 2021 LP Nights On Saturn (Communication) ‘Origins Revisited’ argue that: “Acknowledgement of the West African Islamic influence is sadly still lacking in jazz history books in spite of the fact that it was clearly there […] therefore the current model used to explain the origins of jazz needs to be revised.”

Evidence for this is in Arabic etymology and languages spoken by West African Muslims, as Pat goes on to explain: “African Muslims were present in America, and [we] also have documented evidence that Africans wrote in Arabic, we can see that Jass or Jazz is more likely to be of African origin […] it’s the word for espionage and to look into a matter deeply.”

Pat’s commitment is to the importance and power of probing in and into ‘jazz’, a “looking into things deeply to scrutinise” as he put it in a 2021 essay called Why The Word Jazz Matters, published in Arcana X: Musicians On Music,. It is an awkward wealth of investigation – looking for the history unseen, missed, overlooked, or ignored, or blocked and hidden. Antonin, Joel and I, in our different ways, have been digging away at practices, ideas and techniques too. ‘Jazz’ as a shared research. A collective going deeply into something, an investigation that needs the collective for the investigation. Of course, still, economically, it is very difficult for an artist to probe in this way.

On [Ahmed]’s November ‘day one’ the group had no name, or plan, or structure beyond the aim to explore and to discover what emerged. It was a project of the imagination. A mysterious investment. A sincere, synthetic experiment in, and celebration of the unknown. As we moved into the mystery of Abdul-Malik’s own synthesis we were not ‘concerned with reconstruction and “authenticity”’. We wanted to imagine, together, through the mysterious, into something new. We didn’t want to sound like Abdul-Malik, we wanted to imagine and investigate like Abdul-Malik. We approached this, together, with the deep attention, humility, respect and imagination it demands. And inevitably as a deliberately ‘classic’ jazz quartet of drum kit, double bass, alto saxophone – and piano (with the ‘limits’ Abdul-Malik notes above). What occurred then, and emerges and exists whenever [Ahmed] play, is an aggregate awkward wealth. We make a space to open and hold it, so we can all patiently investigate, inside, look deeply into what each instance has to offer.

This has a particular and specific feeling and consistency – stretchy, stretched and stretching. It is the four of us – with our individual ways and individual paths – at on(c)e, together, (un)folding, balancing, stacking, synthesising and stretching patterns/shapes into seemingly endless permutations and fractions. This togetherness occurs in the ‘nows’ of playing (or the thens and potential whens that allow for contemplation, reflection, imagination and learning about the past and future. Tradition and imagination. A wholesome thing, and a whole something – cerebral and visceral, conceptual and sensual, logical and spiritual, technical and mystical – ‘one’. A ‘one’ that is equally concerned with what it is and knows, and, the potential of alternatives and things unknown, ignored, overlooked, and unnoticed. A ‘one’ in Joel’s words so extreme and stretchy as to be (potentially), at once, a ‘many’, and ‘an untied shoe on a dancefloor’.

“Let me check,” the bank employee explained over the phone in her calm, slightly-muffled Geordie accent. “I can see it’s been blocked. There’s a note on the file. ‘Who is Ahmed?’ They are asking who Ahmed is. They need to know more about the transaction [before they can release the funds]. Can you tell me who he is?”

This was a telephone conversation between me and the bank. I explained (as a complex of ideas/realities/emotions settled into brain-place) my relationship with ‘[Ahmed]’. And she explained, in turn, that it was not the bank she worked for (my bank) but a supra-bank in New York (‘controlling interests’?) that had blocked the transfer of funds from my bank in London to James G. Spady in Philadelphia because of the (sinister? menacing?) reference I had used with the payment: ‘[Ahmed]’. The suspicious, the ‘unknown’ – alarm raised, payment blocked. Incredible, resonant, telling and very wrong.

This was summer 2019. That spring we had asked Spady to write the liner notes for [Ahmed]’s second LP – Super Majnoon (East Meets West). So the payment was for ‘AHMED ABDUL-MALIK ZIPPING PAST NOTE/SOUND STRAIGHT UP INTO COSMIC SILENCE’ – the text that he produced, where further questions are asked (for example):

MALIK: Maybe they just did not want to hear it.

MONK: Why? Unless someone prejudiced them. It’s like somebody prejudiced them. It’s like somebody told them, ‘don’t listen to it!’ What if they open their ears and listen?

That transfer never did reach him. I called it back, in the end. When, simultaneously, I sent the payment again, sans the word ‘[Ahmed]’ as reference, it sailed through the same day. “Let’s not forget’ Edward George suggested at Glasgow’s Civic Halls on Friday April 1, 2022, “the raison d’etre for Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s project is to get away from the horizon of white American supremacy […his work’s] place in an avant-garde, or its opening as an avant-garde of its own, is framed if you want by […] two concerns: an engagement through Islam with the limits and the horrors of white American supremacy on the one hand; and on the other an engagement, from a distance, with the still present legacy of British colonialism.”

He said this during the first iteration of his ‘Strangeness Of Jazz’ – a live broadcast, communication, dialogue, discussion, another (strange) instance of, investigation focussed on Ahmed Abdul-Malik and [Ahmed]. Embedded within this open, live broadcast of unknown shape, alongside and within Edward’s looking deeply into matters through words and playing of records, [Ahmed] talked too, and played live – a spontaneous, re-imagining and looking into ‘Communication’ (the original one of which is on Abdul-Malik’s 1962 LP Sounds Of Africa, and another ‘one’ of which appears embedded in our third LP Nights On Saturn (Communication)).

‘AHAD (33rpm)’ is the other of the 7” single’s ‘ones’. It is the encore we did in concert at Cafe OTO on December 9, 2019. after that concert the world was COVID-changed. [Ahmed] did not play together or see each other for almost two years, dispersed in our different life-worlds: Antonin in Paris, Joel in Berlin, Pat in Oxford and me in London. The compelling one-ness, the unique feeling of being [Ahmed], and our investigative purpose, has been made even more salient by this absence – our union as a group, and our union as a public in sound: at once an ontology (physical, emotional, sensual and spiritual), school (test and education) and celebration (or party).

Surfacing and tapping a kind of open, potential-rich strange-ness – again the awkward wealth of investigation – is at the core of what [Ahmed] do, and what Ahmed Abdul-Malik seemed to do.

In his 1963 interview with Bill Coss in Down Beat, Abdul-Malik says he is planning on a concert at the Brooklyn Museum in company with Japanese musicians. I don’t know if this concert did happen after all, but the rich open optimism of the (awkward) idea, the energy in the (awkward) potential of the (investigative) prospect is something rich to imagine. And this itself is what Ahmed Abdul-Malik’s ideas and music can seem to be: a kind of stretching, limber, inclusive, accommodating and radical vision of synthesis, open structure(s) – a wealth of investigation. The inspiring energy of this stretches (both) back and ahead – again, at once memory and promise. Like Abdul-Malik we can all imagine, probe and venture, investigate together, in dialogue and communication, through (and within) the mysterious, awkwardly, investigating our way back into something new – again, and again, at once memory and promise.

[Ahmed] perform at Skaņu Mežs Festival in Latvia on September 24, find out more here.

This text is composer and improviser Seymour Wright’s contribution to a series of essays, commissioned by REMAIIN (Radical European Music And Its Intercultural Nature), a project that investigates non-European cultural influences on the experimental, avant-garde and innovative music of the present and the past. It is co-funded by the Creative Europe programme of the European Union.