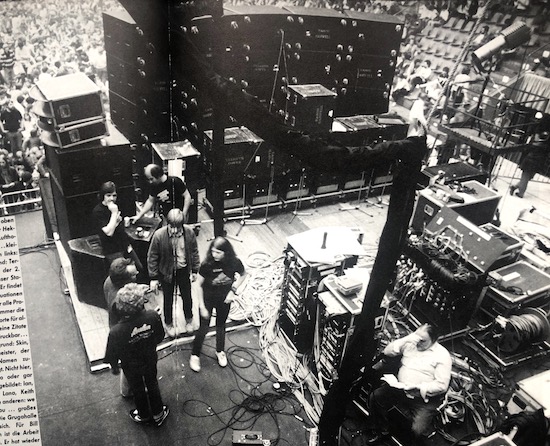

Photo: Alain Le Garsmeur

IT WAS 28 APRIL 1978 when Iggy Pop wandered into my life, and when the clock struck midnight I would officially be twenty-one. As only someone like Iggy could, he turned my three-week break between Status Quo tours upside down.

It felt strange to be able to say officially, ‘I am an adult!’, like I’d reached a milestone of sorts. Otherwise I didn’t feel any different. I’d never envisioned making it to such a ripe old age. That desperate need to keep moving I’d had since I was a kid was by now a thread in my fabric. As long as I stayed in the present and didn’t look closely at myself, I could stave off feeling the lack of self-worth and depression that always lurked just below the surface. The difference between what I showed the world and what was really going on would have shocked most. I expected nothing and had even lower expectations of something lasting long enough to be enjoyed, really taken in, to become a real part of. Always teetering on the edge. I was living one day at a time, and each day like it might be my last, as if I was a passenger being hurtled down my very own Highway to Hell – but I didn’t care, that was just how it was. I was rudderless.

At the time I was living in a flat just off the Kings Road in the World’s End district of London. I shared this place with the landlord, Jack, his brother and a friend named Val. It was in one of those massive old U-shaped apartment buildings with a courtyard in the middle, built around the beginning of the twentieth century, with a marble entrance and sweeping staircase that wrapped around the open metal cage lift. The building had the grand name of Ashburnham Mansions, and the flat was just as grand. On the rare occasions I had time off between tours, it was a great place to try to call home.

I’d just started a three-week break between Quo tours and was already bored. I could never sit still for long. I’d been in a funk all day, and I was half-heartedly thinking I should go out somewhere. I had never made a big fuss about my birthday, but this time I was feeling as though I should do something about turning twenty-one and being legally able to do all the things I’d been doing for years. I wasn’t sure how this whole adult thing was supposed to work, so maybe it was better not to draw attention to it, just in case I was supposed to start acting responsibly all of a sudden. The fact I was still here, still standing, would be enough for now.

As I hadn’t bothered to tell anyone about this milestone, I felt it might be a bit late to start planning anything, although in London you could get a party together on a moment’s notice and easily keep it going for twenty-four hours. I didn’t lack options – I just wasn’t feeling it.

Photo: Manfred Becker

The Marquee Club had become my stomping ground, my usual place to start off a night’s entertainment, as it was right across from Status Quo’s offices. Jack Barrie, the manager, let me in for free and would slip me drinks, while denying the likes of Billy Idol alcohol as he was ‘too young’. The funny thing was, Billy is two years older than me, so I’d be the one slipping him the odd drink.

Richard Branson had opened a new club, The Venue, that was hot at the time and I had a standing place on every guest list in town. I could go to Dingwalls, The Rainbow, Hammersmith Odeon, or the punk rock Vortex Club if I wanted rough around the edges.

The phone in the apartment had been ringing all day for Jack, my roommate, who’d just signed on as tour manager for Iggy Pop’s upcoming TV Eye Tour. It seemed the band were having some problems in the rehearsal room, and Jack couldn’t be found. I’d answered the house phone a couple of times, and each call got a little more desperate and a little less polite. There was a bad buzzing sound through the PA that nobody could figure out how to get rid of. After yet another angry call, as there was still no sign of Jack I offered to go over to try to sort it out. I was really doing it for Jack, as they were threatening to sack him on sight.

Off I went to the rehearsal room, hoping I could stall them long enough for Jack to turn up. I walked into the midst of a rather unhappy bunch, consisting of both band and crew. I didn’t recognise anyone, and I didn’t know anything about Iggy or the band backing him. While the rest of the band were huddled on the stage area, and the crew acted busy trying to fix the problem, Iggy came towards me to introduce himself.

Straightaway, I knew there was something dynamic about this guy. While Quo were all-round nice guys, with a clean-cut, denim-clad, approachable working-class image, here was something completely different. This was a raw energy I hadn’t seen before. This was the other side of the working class: the unemployed, the disenfranchised, the anti-establishment. All rolled up in a ‘five foot one’ snarling package. As he swaggered over to me, he resembled a sleek feline predator; he was bare-chested, wore silver leather pants and had piercing eyes – the perfect combination of good looks, trouble, and what turned out to be a great and exciting talent.

I suddenly felt happy to be there. This was just what I needed – a change, something that embodied the feelings I’d had my whole life of living for the moment. And here it was, crossing the room to talk to me. I was soon to discover there were a lot of layers beneath that punk exterior.

I had no idea who Iggy thought I was, this girl who’d come in out of a dark, rainy London night to fix his problems. I guess he was just desperate to get on with rehearsing. He introduced me to the sound engineer, and I asked this guy what his crew had done so far to find the problem. The engineer gave me a somewhat cold response and a ‘how dare you’ glare. Remember, these guys had taken a ration of shit from Iggy, they had no idea who the hell I was, and if I fixed the problem this would make them look bad. The whole crew seemed sceptical of me – to put it nicely. I could see on the sound guy’s face that he didn’t think I could help at all, but maybe I could make his crew a nice cup of tea while they got on with ‘men’s work’. As I was under no obligation to be there, I was again wondering why on earth I’d bothered to volunteer.

I took a deep breath and explained that he had nothing to lose. And if I didn’t fix it, at least the pressure would be off him; he could blame me, and I could disappear back into the dark and rainy night, never to be heard from again. I’d found over the years that if I had to deal with a man who was resistant to a woman taking charge, the words ‘what if we try it this way’ got me a lot further than ‘I think you should try this’. Simple, but it worked every time. It worked so well that I would use the ‘I’ version when I wanted to piss someone off.

Photo: Alain Le Garsmeur

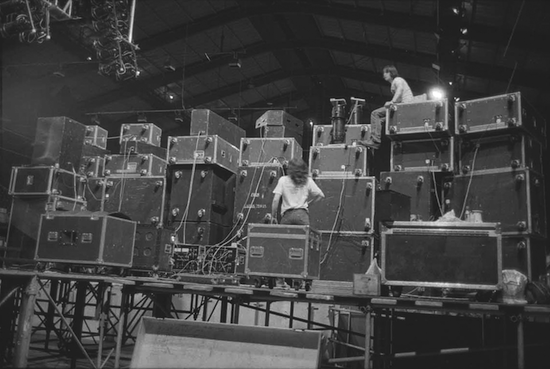

When the engineer agreed that he and his crew had nothing to lose, we all went to work. This wasn’t an easy task, as the room was a big mess. We had to contend with the poor condition of the equipment, the dodgy-at-best power supply, the cable runs all over the place, and a new crew just learning the equipment set-up – and Iggy, of course, wanting to keep rehearsing while we were troubleshooting.

After several tries, we found the only way to get rid of the loud buzz was to ground-lift the sound system. Not the ideal solution, but as Iggy wasn’t prepared to stop rehearsing while we fixed it, this would just have to do. It was a very punk rock solution, though, and as long as nobody touched a plugged-in instrument while touching a live mic, it would work. Hopefully, no one would die. The crew and I made this clear to the band and said that we didn’t want them running the risk of getting shocked (or worse), although a couple of the crew might have felt differently by this time. Our solution wasn’t permanent, but someone from the production company could come out the next day to fix the problem, which was probably in the wiring of the building.

Everyone agreed, and I prepared to make a speedy exit, not wanting to be around if it all went south. Now, a speedy exit from a rainy South London rehearsal room in the wee hours of the morning wasn’t going to be easy. Not the best neighbourhood, I might add. And at this point any birthday plans were out the window, as it had taken a couple of hours between songs to make tea and fix the problem. Now it was one in the morning. (Yes, I had made tea and brought it to the Doubting Thomas sound guy – my sarcasm wasn’t lost on the room.)

The good news was that I really liked the music I’d heard. Finally, something down and dirty with both talent and substance, a sound from Detroit very different from what was being passed off as punk in most of the London scene at the time.

The rehearsals had started up again, but I chose to wait outside for my taxi. I always felt a bit self-conscious just hanging around musicians if I didn’t have a work reason to be there. I’d done my bit. It was a long wait; if the rain hadn’t still been coming down, I would have started walking back to the flat.

Then Iggy appeared. ‘Come inside,’ he said. ‘Hang out with us; we’re taking a break.’

Sure, now they’re taking a break! Typical.

I’d had just about enough by this point. My birthday night had been spent with a roomful of grumpy strangers – not exactly how I’d envisaged it.

‘No, thank you!’ I said. ‘I really have somewhere else to be.’ This was a lie, as it was after 2 a.m. and swinging London had been safely tucked away for the night.

It was probably the first time anyone had said no to an invitation to watch this group of musicians rehearse. Somewhat bewildered, Iggy asked, ‘What are you heading off to that’s so important?’

Just at that moment my taxi finally arrived. ‘My twentyfirst birthday,’ was my response, and I jumped into my cab and waved goodbye as I left.

Photo: Alain Le Garsmeur

The next morning, Jack was a little standoffish, to say the least. I figured he’d got yelled at and it would all blow over. Later that day, he told me the band wanted to see me, and I should go meet Iggy at RCA, his record label in London. I thought it strange that Jack didn’t thank me for jumping in and helping him out, but no big deal. Curiosity got the better of me, so off I went.

It seems all wasn’t well between the band and their label, and this get-together at RCA was meant to be an icebreaker for both sides. Iggy would be introduced to all his label people in London, and they would hang out together in an attempt to bond with him and pacify him. For a little guy, he really could be a force to be reckoned with.

Iggy had completed his obligations to the label with his TV Eye album, and he wanted out. As record labels and Brits do, they pretended everything was just fine; there were no problems at all, and it was going to be a great tour. To seal the deal, after much fanfare the label presented Iggy with a life-size Nipper. Now, you might recognise Nipper as the dog on the HMV logo, the company that had become RCA. This was a rare honour – in fact, a life-size Nipper had never been bestowed before. Having said that, what the godfather of punk was meant to do with a large plastic dog on the eve of a balls-to-the-wall European tour, I don’t know.

Well, Iggy didn’t know either. Immediately after the handing-off ceremony, he presented Nipper to me in front of everyone. ‘Happy birthday, Tana!’

I was ecstatic. The RCA label personnel, not so much. I’d wanted a dog for ages, and this one would do just fine for the moment. At least it wouldn’t miss me when I went on tour.

I was happy, Iggy was happy, and the record label people were gobsmacked. Iggy, his band and I all made a quick exit together, laughing and mumbling something about having to rehearse.

But wait, there was more good news! Iggy wanted me on the tour – Nipper was just a bonus thrown in to piss off his label. I thought this was great, as I was starting to really like this strange, intense but funny little guy, with a nervous energy that transferred to his performances. And this tour would fit in to my time off from working with Quo. Nice! My job description hadn’t been clarified yet, but I was to go to the production company the very next day and help get all the equipment ready for the tour.

I was looking forward to touring with Jack. We’d always got on well but never worked together, so I thought it would be fun. In the days before we were to leave on the ferry to Europe, I didn’t see him, but I wasn’t bothered as I figured we had time to catch up on the road.

When I arrived at the dock, I still couldn’t see Jack. As tour manager he should have been an obvious presence, and he was six foot seven, but nowhere to be found. I presumed he was already on the ferry with the band. Finally, I asked after him. Iggy’s manager told me that Jack wouldn’t be with us: he’d been fired, and Iggy wanted me to take his place.

This wasn’t good. Not good at all. I wasn’t a tour manager, and Jack was my friend and landlord. Shit! Tell me this isn’t happening, I thought. I like where I’m living.

After I’d declined, they still wanted me on the tour. So what was my job to be? I don’t believe in giving someone a title only to justify their existence on a tour. Everyone in a crew depends on the others to do their jobs to their utmost capacity. In difficult situations, resilience and teamwork can be what holds it all together.

What I’d thought would be a three-week bonding experience for me and Jack was now something totally different. It wasn’t going to be easy – there was still going to be a lot expected of me. I was to work closely with Iggy while making sure everything was good on the production side. I would also work on the lighting crew and stage-manage; that way, keeping tabs on both sides. There’s no point keeping the star happy if it goes to shit every time he walks onstage.

The new tour manager probably saw me as a bit of a challenge, with me and Iggy getting on so well. This was never my intention, but I’ve learnt over the years that people either take you as you are or have some preconceived notion of you that can be difficult to change.

The crew filled me in initially on who the band members were, as I had no knowledge of the early US punk scene or the importance of these individuals in that milieu. Only by getting to know the band members personally did I truly understand their dynamics. I was about to be educated on this part of US music history.

LOUD by Tana Douglas is published by HarperCollins