There are many subjects on which music journalists are capable of being mercilessly passionate, but none more so than the under-rated album: that work whose manifold virtues were lost on that heedless rabble known as the record-buying public, but which should have sold several zillion copies, and by golly would have, if only these dunderheads would listen, etcetera.

In 1995, the music weekly Melody Maker, for which I was at the time writing, decided to exploit this grimly evangelical tendency among its contributors. That year, the March 4 edition of the Maker was packaged with a slender paperback entitled Unknown Pleasures: Great Lost Albums Rediscovered. It was a collection of essays in which Maker hacks were given roughly 2,000 words a time to exhume whichever treasures they wished from the depths in which popular indifference had buried them.

Some of these records had been biggish at the time then forgotten, others more or less entirely ignored all along. But they’d mostly been wandering in the wilderness awhile, since the 1960s, 1970s or 1980s. I wrote about one which had been released a matter of months previously. The band concerned managed, I think, to find this bleakly amusing.

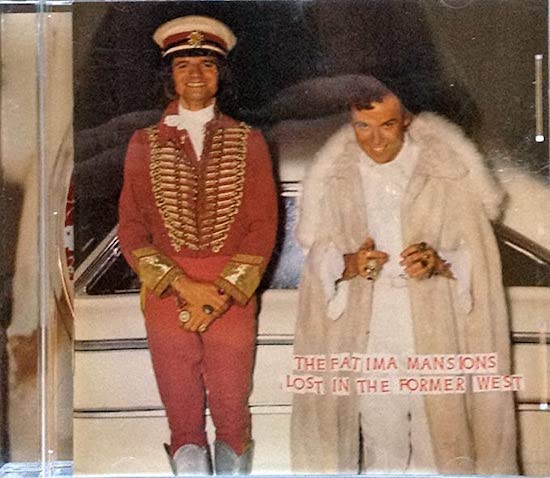

The album was Lost In The Former West, the fifth and – it turned out – last album by The Fatima Mansions. The Fatima Mansions, named after a decrepit Dublin housing estate, were the band formed by Cork songwriter Cathal Coughlan after the demise of his previous band, Microdisney, themselves favourites of overly zealous rock writers: my ‘Unknown Pleasures’ essay also considered Microdisney’s equally outrageously disregarded valedictory statement, 1988’s sumptuous 39 Minutes, a record which sounded something like an Irish Phil Ochs blessed with the voice of Roy Orbison singing to the arrangements of Billy Sherrill.

I had started getting to know Cathal in the early 1990s. We first met when I interviewed him for Melody Maker around the release of The Fatima Mansions’ second album Viva Dead Ponies. As I loved The Fatima Mansions to distraction, and nobody else at Melody Maker seemed all that interested, I interviewed Cathal pretty frequently, often in peculiar circumstances: backstage in Belfast at an aftershow party inexplicably gatecrashed by a gang of fortunately affable Loyalist skinheads; on a rollercoaster at a funfair at Whitley Bay, for reasons I no longer recall; on the tour bus bearing The Fatima Mansions to their opening slot on U2’s Zoo TV tour at the Palau Sant Jordi in Barcelona. This was accompanied with a parping soundtrack of the Mansions’ on-tour alter-ego group, the inept if enthusiastic brass ensemble they called the Tower Of Crap, opening the sunroof to accommodate their trombone slides. On Zoo TV’s merchandise stalls, the myriad U2 gear was joined by The Fatima Mansions’…