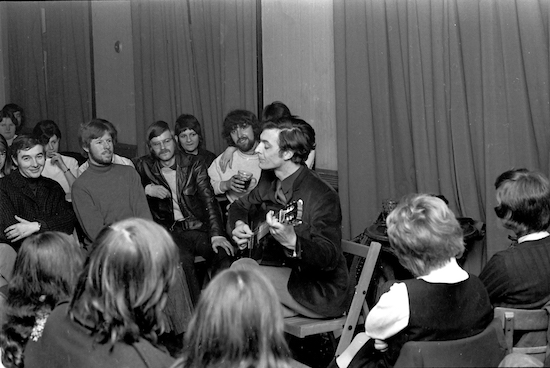

Jake in 1971 at the Recreation Folk Club Colchester photo credit Stuart Allison 1971 Colchester Express Archives

In Search of The La’s: A Secret Liverpool culminates with its author, M. W. Macefield, tracking down Lee Mavers in a suburb of Huyton. The subsequent – and surely inevitable in these cases – outpouring of praise and adoration is cut short when Mavers reminds Macefield that he’s “only a man, la’, just a person”. Like The La’s’ reclusive genius, Jake Thackray was also at pains to assert what he saw as his normalcy, that he was “only a man… just a person” first and foremost.

But how to square with his very abnormality, his overwhelming Jake-ness? It’s one of the dominant themes in Paul Thompson and John Watterson’s Beware of the Bull, an excellent new biography of the Yorkshire chansonnier. Thackray was uncomfortable with the fame that had been thrust upon him almost accidentally; it was the wrong sort of success. He invariably positioned himself as a normal bloke (once refusing a hotel because it was “embarrassingly posh”). But this was often in contrast to his unique features, strange voice, and incredible talent.

Beware of the Bull nimbly identifies the various push and pull factors in his existence: life vs art; the Catholicism that he called both his “backbone” and “burden”; the mother that encouraged his music vs. a reportedly unloving father; the roots put down in Leeds then Monmouth vs the fly-by-night hurly-burly of being a “performing dick”, as he so loved to describe himself; the desire to play for free to fifteen people in a pub vs trying every possible excuse to avoid playing a well-paying 1,500-seat venue; the songs that he characterised as “the holy and the horrid”; the way he was so of his time, yet also so far removed. There are even more of these important binaries, and it’s clear that Thackray felt them all.

Perhaps it should go without saying, but Beware of the Bull, the first notable attempt to profile this singular talent, stays true to the idea of a biography being, ultimately, about one life, about the person who wrote that wonderful music rather than the songs themselves. It’s an appreciation of the man in both senses of the word: why he remains a unique and special artist, as well as being a pacy, warts and all conspectus, a dash through his remarkable story.

Thackray’s path is traced from the deprived areas of Leeds in which he was raised, to Durham University where he read English Language and Literature, before teaching in France, and Leeds. Taking up music quickly led to an odd place in the mainstream, broadcasting strange satirical songs to the nation’s TV screens, and writing albums populated with a wellspring of unusual characters. Dwindling success followed, and the end of his life saw him eke out an ostensibly meagre existence in a council flat, drinking heavily and bell-ringing on a Sunday morning (the only music he permitted himself to play). Equal weight is given to the different forms his songs took: the bawdy humour and dazzling wordplay found in ‘Sister Josephine’ and ‘The Lodger’; the rustic beauty of ‘Go Little Swale’ and ‘The Little Black Foal’; the quotidian surrealism of ‘Bantam Cock’ and ‘The Cactus’; and darker, more involute material like ‘The Bull’ and ‘The Remembrance’.

Thankfully, as Thackray would have preferred (being surely embarrassed at the very notion of a biography), there are no weighty codas or unnecessary prologues that describe the state of the nation or Thackray’s far-reaching impact on musicians today. Instead, loose themes are baked in. It’s part history of the music industry’s changing face, a psychogeographical discussion of Yorkshire, Monmouth, and France, a study of the tension between inherent qualities and learned qualities, the way one’s background, origins, even DNA, continue to exert an influence even when pushed beyond one’s station, woven deftly into the account of one singular man. To slightly bowdlerise an introduction to a song Thackray used to give, “it happens to be a true story… it’s not a story with a punchy bit at the end, it’s not a moralising story, or a whimsical, or a sentimentalising story; it’s just a story”.

Jake performing in April 1969 at The Big Window Hotel Burnley colour photo credit www.bcthic.org-Burnley Civic Trust

In a review of Mike Love’s autobiography for The Guardian, Bob Stanley writes that it was an interesting “science experiment: if a jock were thrown into the heart of the 1960s cultural revolution, how might he emerge?”. Beware of the Bull does a good job of showing what would happen if you put a no-bullshit working class Catholic Yorkshireman into a well-heeled, Aqua Velva-d world populated with “rascals”. For instance, he “attended a Conservative Association barbecue because so many friends were going, but first leafleted the assorted Land Rovers, Volvos and Saabs in the car park with ‘Coal, not dole’ flyers, declaring that this was to ‘atone for the sin of hobnobbing’ at a Tory ‘do’”. He also regularly butted heads with agents, producers, and music industry salespeople. His anti-capitalist principles meant he even turned down a lucrative deal with Dulux to appear in an advert that would have solved his family’s money problems.

A biography works best when it adds local colour, humbly shades in knowledge gaps, situates its subject in a loose timeline, when its author is transparent, and there’s clear blue water between hunter and quarry (there’s no ‘Jake: My Story’ attempts to point us to any pre-existing connections between author and subject). Instead, the rich tapestry is woven from a cache of various media found mouldering away on ancient internet pages and physical archives up and down the land. These are perhaps the most riveting aspects of the book.

Thompson and Watterson were granted access to hitherto-unpublished personal papers, as well as lyric sheets for unknown songs, lost recordings, and television programmes from which only snippets have been available on YouTube. There are tantalising mentions of the unrecorded song about the names of soldiers’ wives on the Cenotaph, a rendition of ‘Old Molly Metcalfe’ apparently sung over a bed of eldritch electronics, and a rewriting of ‘Country Bus’ in the past tense thus “[changing] his celebration of the bus and its motley passengers into a bittersweet lament for a way of life … now gone.” The diary entries are hilarious and ominous often in equal measures: see “Forgot ‘Cactus’ and apologised winningly. Forgot ‘Fine Bay Pony’ and apologised defeatingly” or “First day back [after Christmas holidays], and scared, scared, scared.”

A line from the song ‘Beware of the Bull’ runs “if you must put people on pedestals, wear a big hat”. It might be worth diving into the “warts and all” aspects I mentioned, since they are, thankfully, not ignored. The main lyrical offenders are found most obviously in ‘One Of Them’ and ‘On Again! On Again!’. ‘One Of Them’ (a song which contains the n-word) is identified by the book as a way of “condemning the prejudice-based humour widely regarded as acceptable in the 1970s”. That said, the deployment of the n-word is clearly wrong in all contexts – listen to the song, then take a step back, and think about whether it’s necessary to hear. Thackray was obviously more well-versed in class and unionist struggles than anti-racist and feminist ones. With regards to ‘One Of Them’ I think you can hold the two ideas in your head at the same time: that he can be applauded for attempting a progressive take on the grisly prejudice-based humour prevalent in the 1970s and that a firmer line between a denotative content and the manner in which it’s expressed could have been drawn.

‘On Again! On Again!’ is the principal offender in a handful of examples of sexism that dogged Thackray towards the end of his career. Thompson and Watterson deploy Thackray’s own, rather breathless, explanation that ‘On Again! On Again!’ lambasts only “some women” who talk too much, and that he might “cheerfully have done it about a bloke” This defence falls rather flat when you imagine it extrapolated to other jokes stereotyping different minorities.

Still, that he registered the concerns of those protesting against his songs is something. If ‘On Again, On Again’ is taken as a measure of his sexism, then why not take ‘The Kiss’ (dealing with sexual self-determination) and the female liberation-based ‘The Hair Of The Widow Of Bridlington’ and ‘The Castleford Ladies Magic Circle’ as counter-evidence against? Once again we can hold the two ideas in our head: that ‘On Again! On Again!’, as well as some references to women as little more than body parts, can be counted as deploying grisly vernacular and that other songs he wrote were timely, perceptive, and even progressive portrayals of women. It’s another paradox that Thackray embodied. The man who conjured the glorious and total “unrepenting, undeterred” independence of a widow, gave a voice to elderly women and single women, and even wrote tenderly of the infant breastfeeding “as on an endless sea” is also he who penned the series of unsightly blottings in that bulging lyrical copybook.

In the same way that the authors use Thackray to come to his own defence of ‘On Again! On Again’, Beware of the Bull hangs opinions and interpretations not on onerous analysis (leave that to me) but various excellent sources like Thackray’s ex-wife, son, agent, close friends, and the man himself. From the dwindling audience numbers, to those accusations of being stuck in the past, to the growing stage fright (“scared, scared, scared”), to his alcoholism, it is from these sources that a grim augury starts to percolate.

Ralph McTell said of Thackray’s increasingly frequent performance absences, “I think it was a sign of things coming to a head. That man would have swum a river on fire to get to a gig before, because he had made a promise to do it … It’s indicative of deep turmoil brewing, I thought.” Videos of Thackray during the period where he was, if not in actual decline, looking towards the stage exit, make for sad watching and reinforce McTell’s worries. Though in a performance at the Cambridge Folk Festival he looks magnificent – giant, chiselled, veins popping out of brawny forearms from the exertion of those quicksilver guitar parts – he’s also pouring with sweat, voice occasionally cracking, his fear occasionally revealed by equine whites of eyes.

Jake performing in 1971 at the Recreation Folk Club Colchester photo credit Stuart Allison 1971 Colchester Express Archives

What is written throughout the book like a message in a stick of Brighton rock is Thackray’s total unsuitability for fame. The world of late nights, big crowds, easy access to booze, and a precarious financial situation is not the place for someone with insomnia, stage fright, burgeoning alcoholism, and a total ineptitude with money. Beware of the Bull tees up these things with a visceral inevitability – early success, the years of plenty, waning fortune, destitution, death – but when they happen they’re still every bit as affecting as when you first heard about them.

Perhaps the most revealing part of the book, however, comes right at the end. Those familiar with Thackray’s life will know he went bankrupt, stopped playing music (save for ringing church bells), and alcohol took an even greater hold on him. These things are true, of course, but what becomes evident was that Thackray in fact relished the opportunity to simply be a member of the small Monmouth community in which his one-bedroom council flat was situated, to be ‘Jake’ as opposed to ‘Jake Thackray: performer’. Thackray’s son Sam says that “as a man he found a stable modus operandi. He loved Monmouth and he loved the people there; he liked the church and being involved with Amnesty International”. Likewise, Ray Brown says “Jake had a realistic assessment of himself. He knew he had messed up his broadcasting career through drink, but he never seemed to be miserable or unnecessarily self-critical.”

In many ways, the end of the book recalls a little turn from one of Thackray’s songs, that delicious moment where given information is turned on its head or viewed through a different lens. It’s a genuinely moving revelation, and one that throws into sharper relief some of the murkier aspects of his later years. In the end, Thackray became “only a man” and finally “just a person”.

Beware of the Bull – The Enigmatic Genius of Jake Thackray by Paul Thompson and John Watterson is published by Scratching Shed Pubishing