A bottle fight at Leeds Festival 2002, in 2002 camera phone quality

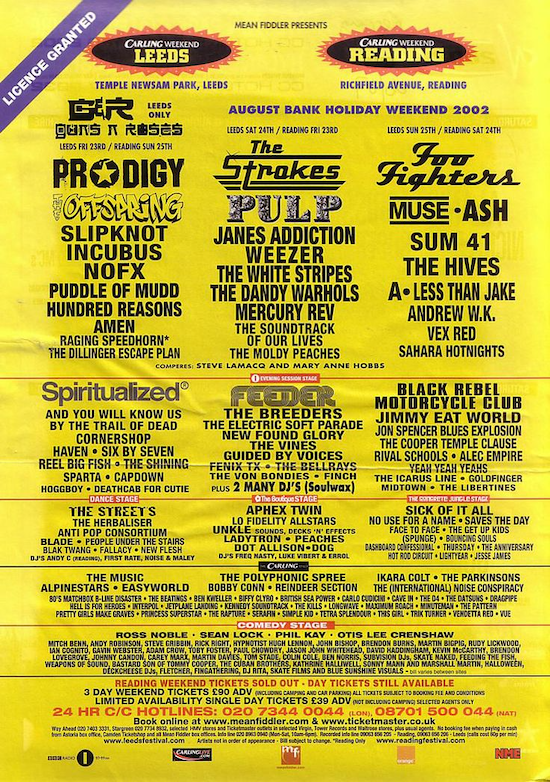

"For the love of Grohl," I asked myself while watching Netflix’s Trainwreck: Woodstock ’99, "where is the three-part documentary on Leeds Festival 2002?" I am happy to provide eyewitness testimony. Besides an Executive Producer credit, my fee is two tickets to see …And You Will Know Us By The Trail Of Dead because, twenty years later, I have moved on in very few ways.

The event was, in the archaic literal sense of the word, a riot. While it did not reach the same level of carnage as Woodstock ’99, things did get out of hand. On the final night, armoured police were deployed as campers went on the rampage, setting fire to blocks of temporary toilets, yanking down fences and inflicting further mindless destruction. Helicopters with searchlights circled overhead. The police were pelted with projectiles. Gas cannisters exploded into the sky. You half expected Danny Glover to leap out at any moment like in the iconic opening moments of Predator 2. By Monday morning, £250,000 worth of damage had been caused. The Temple Newsam estate said it would never host the festival again.

As Stuart Heritage points out in The Guardian, one of the reasons that Netflix’s Woodstock doc is so strong is that the event was particularly well-documented. The place was full of camera crews as well as "every rock photographer on the planet." At Leeds, I had a Nokia phone and disposable Kodak. You’d think you had nailed some masterful action shots of Colin from Hundred Reasons in full emo flow. When the developed photographs were collected from Boots, they’d all be identically useless images of a pitch-black stage surrounded by blurred lighting. Most of the media went to the Reading leg of the Carling Weekend, of course, which is nearer that London they have down there. One year we spotted a young Vernon Kay, making the move from a modelling career to telly presenter, vox-popping people in bucket hats. That was about as glamorous as it got ‘round our way.

The show I’m pitching will have to rely on talking heads rather than raw footage, then. I’m sure Muddle Of Pudding has some gaps in his schedule. Buckethead never speaks out loud, apparently, but perhaps he can gesticulate his reflections on Axl Rose’s eccentric rider demands. We’ll hold a photograph of all the litter and other debris in front of Andrew W.K.’s face until he bursts into tears like the Native American at the end of Wayne’s World 2. Or we could go down the historical re-enactment route, like when a struggling actress pretends to be Louis XIV’s mistress for Lucy Worsley.

Is Robert Duvall available? "Portaloos, son. Nothing else in the world smells like that. I love the smell of Portaloos in the morning. One time we bombed them for 12 hours… The smell, you know that chemical smell? The whole field smelled like piss, chlorine and melting plastic. Someday this festival’s gonna end. By which I mean, relocated to Branham Park…"

Of the actual performances, even with all the hype The Strokes shouldn’t have been headlining with only one album under their belt. Their nemeses, The Icarus Line, were life-affirmingly — life-ruiningly, even — tremendous. It was like seeing The Stooges in 1969 or The Birthday Party in ’81 (I imagine). When informed they only had time for one more song, the band launched into Mono‘s longest and slowest number and had their sound cut for such insolence. I realise this goes against the advice in Joe Thompson’s Sleevenotes book. He implores bands, particularly those on multi-act bills, to start punctually and end on time like courteous grownups. ("Make all the noise you want in your allotted slot.") I have to say though, at the time it was thrilling. The abandoned song would only have eaten into Alec Empire’s allowance. [Insert shrug emoji]. Perhaps seeing them take something too far and being forced to stop was an omen.

Riots or no riots, Reading always received more media attention than Leeds. It used to annoy me that, whenever music magazines published their articles on THE GREATEST GIGS OF ALL TIME EVER, besides a London band blowing the minds of a few Mancunians in 1976, there was a distinct sense that nothing noteworthy had ever taken place further north than Donington Park. (Incidentally, in Steve Hanley’s memoir about his time in The Fall, it’s made clear that it wasn’t the breathtaking brilliance of the Sex Pistols that wowed on that night. "Surely we don’t need some scruffy Londoners coming here to make a racket and scream abuse at us", thought Hanley, "when the chances are we can do that ourselves." He and Marc Riley left before the end to grab a bag of chips.)

In my youth, I also resented the fact that Reading Festival always seemed to get the secret sets and starry guest spots. In 2002, The Strokes were joined by Jack White from The White Stripes. (Wow!) At Leeds, they brought out Robert Pollard. (Who?) For once though, Leeds had one thing over Reading: Guns N’ Roses. Their tour schedule meant they were available for only one date. What a coup! In your face, southerners! The washed-up sleaze rockers were nearly two hours late and this was the limbo-like Buckethead era when Chinese Democracy was perpetually promised and never delivered. "Where’s Slash?" Axl Rose yelled at a heckler. "He’s in my ass! That’s where Slash is! Fuckhead!" What a way to set an atmosphere.

I sometimes have dreams that I’m back at that campsite. Although these aren’t necessarily firebomb-centric it may suggest some mild form of PTSD. I can’t find my tent. Someone’s stolen my tent. The walk from the drop-off point to the campsite lasts an infinity. I am Sisyphus. Instead of a boulder, it’s bags of tinned beans and wet wipes. "All the necessary locations are, ingeniously, situated with minimum thought and maximum distance in between," noted Drowned In Sound at the time. The unhelpful stewards were described in less than generous terms. As a trigger for the unrest, the writer diagnosed "piss poor organisation and sky high prices for everything".

There certainly was a sense that the organisers didn’t give much of a hoot about its own ticket-buying clientele. Back then, it was harder to complain directly to anyone beyond that line of unsympathetic stewards. You couldn’t take to social media like everybody with a smartphone did at this year’s Primavera.

Did the organisers deliberately goad their goers? The festival’s line-ups have become more inclusive, gradually. Now that music scenes are less tribal than before, audiences are more open-minded too. Back then, the scheduling of frock-era Kevin Rowland (1999), Daphne And Celeste (2000; they were brave and they were brilliant) and 50 Cent (2004; pelted with piss-filled bottles, he played the minimum time needed for payment and then left) were arguably transphobic, racist and misogynist decisions, given they were designed to rile the crowd by stoking their baser instincts. The music press treated this stuff as a giggle, which helped normalise it. There’s nothing great about the optics of a field full of white indie and rock fans pelting a token black artist with missiles. Booking Daphne and Celeste as a warm-up for Slipknot and Rage Against The Machine is a bit like screening Care Bears 2 at the beginning of Wrestlemania.

That didn’t happen in 2002, although Punknews.org did report that The Offspring’s set was so lazy that the audience began "the biggest bottle fight in festival history" out of sheer boredom. Guess that’s The Offspring’s fault because they’d gone down well before. I feel a bit sorry for them, actually. They’d been one of the acts accused of stirring up the crowd at Woodstock by, for instance, decapitating effigies of Backstreet Boys. With a more sedate stage show, the bottles still rained down.

I wonder about the booking of "Guns N’ Roses" for Leeds only, though. Will they turn up? When will they turn up? Where’s Slash? Who’s the bloke with the chicken bucket on his head? Is that the fella from Nine Inch Nails? When was Duff last in them, again? Has anyone even listened to Use Your Illusion since circa ’94? Volumes I and II are omnipresent in every branch of Oxfam. Hope they play something off Chinese Democracy, snigger, snigger, snigger. How mad will Axl get and then the crowd in turn? Answer to both: pretty mad. Somehow, Foo Fighters’ headlining set on the final day just wasn’t enough to expel any remaining pent-up frustration, no matter how cathartic the predictable encore of ‘Everlong’.

Smaller scale destruction had occurred the previous couple of years so the "tradition" of drinking heavily and causing ruckus had built up towards 2002. The Leeds branch of the weekend had only been going since 1999 so there wasn’t much tradition beyond that. Reading: now that’s a site with tradition. In the 1970s, Reading Festival had all the biggest names whether they were cool or Ultravox. In 1989 it had Spacemen 3, Butthole Surfers, My Bloody Valentine, Head Of David, Loop and more. Its early ’90s line-ups read like a who’s who of the alternative rock explosion. By the time the festival secured its Leeds equivalent, there was already that sense of seeing Bowling For Soup on every poster, which is enough to make anyone question the ever-escalating ticket prices.

A handful of the riots’ ringleaders, if that’s what they were, got prosecuted. Some called them meathead ruffians. Others saw spoilt and entitled bourgeois kids going all ersatz Lord Of The Flies when away from the parents they unfairly resented. One of the prosecuted was the son of an MP. If you want to talk testosterone, they were all male. Lots more people than those few had gone on the rampage, mind, and many more were egging them on from the sidelines.

Both rioters and weapon-wielding police were a little bit scary but if you didn’t want to partake in violence or face prosecution you could just keep your distance and enjoy the tent-sweated Babybel with rank tinnie chaser. In fact, as groups of young lads stormed along the field we were camping in, tearing down the lampposts that lit the central thoroughfare, me and my pals guarded the one nearest our tents and tried to persuade our more destructive acquaintances to leave it erect. The lights, we explained, were actually quite useful for seeing your way back home from the toilets. Oh wait, the toilets are on fire. After a while, we gave up on our counter-rebellion.

There haven’t been riots on that scale since 2002 but Leeds Festival maintains its aggressive, lairy and occasionally pyromaniac reputation. When I returned as a reviewer in 2015, a gang of LADSLADSLADS randomly rugby tackled me to the floor, poured a freezing cold bottle of water over my head, and then ran off laughing to assault other innocents. I suppose I was grateful it wasn’t urine.

Leeds Festival’s new home at Bramham Park

I do wonder whether, as is so often the case, the rioters simply wanted to be seen and to be heard. The same has been said of certain recent anti-metropolitan voting tendencies which have had far greater repercussions than forcing a festival to relocate.

If Brexit can be laid at Britpop’s door and connections drawn, as HBO’s equivalent documentary does, between the crowd madness of Woodstock ’99, the impotent protagonist(s) of Fight Club and the kind of MAGA-cappers who stormed Washington’s Capitol building in 2021, can a less-than-tenuous link be made between Leeds Fest ’02 and, let’s say, The Labour Party’s diminishing support from northern voters? Between 1997 and 2010, New Labour hardly healed the north/south divide, as proud as we all were of John Prescott punching that bloke with the egg. In 1999, Tony Blair tried to downplay its very existence (the divide, that is, not the egg). On their watch, the gap between the affluent and those less so increased, shamefully.

As I’ve tried to tentatively lay out above, I feel there was a subliminal sense of just wanting to be noticed. An existence acknowledged. But it’s a sobering experience to realise that once you’ve burned down your own toilet block, you’re left to crap in the woods like an animal. "The North had rose again," Mark E. Smith once observed. "But it would turn out wrong."