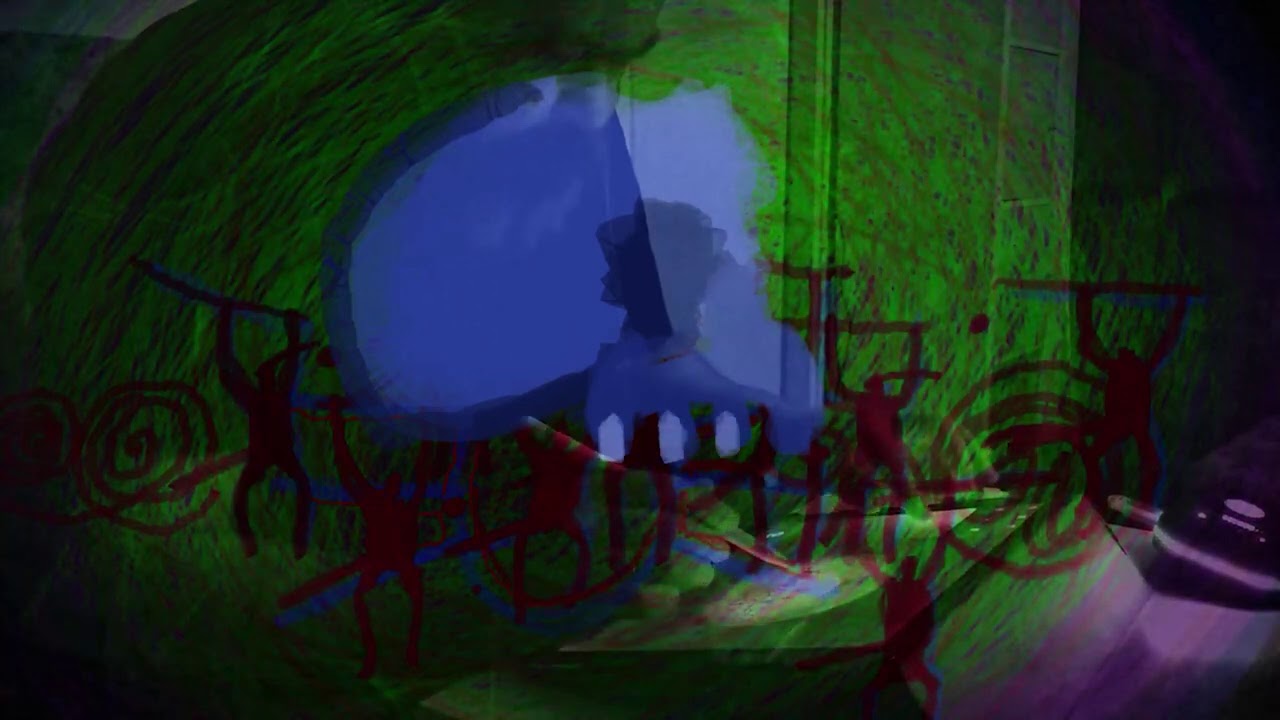

Staraya Derevnya at Tusk Virtual in 2020

“I try to record and listen to everything when we play together,” explains Gosha Hniu, (aka Gosha Shtasel), the founding and only continuous member of Staraya Derevnya. “Sometimes the best sounds come when someone is tuning up, or they make a mistake and miss some notes, or there’s some interference. Those moments often end up in the recordings. There are good mistakes and bad mistakes, and good mistakes are gold.”

Every album from the band, whose core members currently reside in the UK and Israel, feels like an invitation into a space outside the mundane. When playing live, visuals from Danil Gertman, drawn and projected in real time, are an intrinsic part of their performance. Like those visuals’ movement from amorphous constellations of colour into concrete characters and landscapes, Staraya Derevnya swing from flurries of abstract folk sounds into propulsive, swampy grooves. It’s oneiric, but not in a way that is lulling or sleepy. Rather, Staraya Derevnya’s music is full of surreal associations and strange causalities that, like a dream, feel completely natural for as long as you’re immersed in them.

“There’s something strange that happens in Staraya Derevnya. It feels familiar, but it also feels like something that doesn’t exist. It’s like a no man’s land.” says Maya Pik, flute, synthesizer, melodica and occasional rocking chair player in the ensemble.

The band began in the 1990s with an almost totally different lineup. Early on, their approach was more traditional, songs written and then recorded. The outcomes were unique, as shown by debut album Экспедиция, a theatrical, angsty mix of acoustic psyche, brass and an almost Beefheartian sense of strange grooves. Then, after Hniu moved from Israel to the UK, they developed a new way of working around 2016’s Kadita Sessions. They begin with jam sessions and then edit, rework and expand fragments from those into the tracks that end up on their albums.

Over that time, something like a core lineup has solidified for the group, with Pik, Ran Nahmias and Grundik Kasyansky joining Hniu on all subsequent albums. Gertman got involved around the time of their performance at the 2017 edition of Tusk Festival in Newcastle.

The band are cautious about over-explaining what goes into their music. Especially Hniu’s vocals, which move from eerie croons and falsettos into chants, screams and whispers, sung in equal parts Russian and made-up words. “When we talk about it, it sounds postmodern, but it’s totally not,” says Kasyansky.

Hniu agrees: “It seems highly conceptual, but really, it’s just difficult to talk about. Deep down, this is what I care about, but I need to approach it in a way that is playful. There’s nothing worse than taking yourself too seriously. It’s not about being funny, but self-irony is important. You take the music seriously, but not yourself.”

I suggest that their approach is more about being instinctive than something preconceived, and Hniu agrees. “If it wasn’t instinctive, it’d be fake.”

New record, Boulder Blues, feels like a concentration of the energy that’s been evolving since Kadita Sessions. The tracks are propelled by minimal, hypnotic grooves, but around them is a deluge of timbres and textures. You can listen to it on two levels, playing detective and ruminating on the minutiae, or surrendering to the hypnotic cumulative effect. Both are equally rewarding.

The album features guitars from Miguel Pérez. Based in Mexico, his background is in hardcore and metal. He hits a different kind of heavy with his solo project, Skull Mask, which is built on abyssal, steel strung acoustic guitar laments. It’s through this project that Hniu first heard Pérez’s playing.

“When Gosha sent the material for Boulder Blues, I was amazed by the lack of references,” recalls Pérez. “It’s a unique animal, you can’t fit in by playing to a certain style. There’s so much space, it’s wide open for interpretation.”

When I speak to Gertman, Hniu, Kasyansky, Nahmias, Pik and Pérez over Zoom, they’re preparing for a string of dates in the UK to celebrate the release of Boulder Blues. Gertman, Nahmias and Pik are in Israel, Pérez in Mexico, and Hniu and Kasyansky in London.

tQ: When did you start working on Boulder Blues?

Gosha Hniu: It was right before Tusk Virtual [a 2020 online edition of the Newcastle-based festival]. We’d just released Inwards Opened The Floor, and weren’t planning to do anything in lockdown. Then we got the invite from Tusk. It was unusual for us, we came up with our performance in three weeks, we’ve never been that fast before. Part of what we did for Tusk is on Boulder Blues [the fifth track, ‘Bubbling Pelt’], but for the album version we changed it a lot. Miguel is playing on there, he really transformed it. The rest of us also did extra things.

After Tusk Virtual we kept working. We only had a few in-person sessions. It was strange for us to be working more remotely, with less live playing. I think that’s why there’s a clearer rhythm in all the tracks, because we weren’t playing in a room together as often.

When I first heard Staraya Derevnya, I imagined there were multiple vocalists, but in fact it’s mostly Gosha. Can you talk a little about where this variety comes from?

GH: It’s not like we’re writing songs where you have a backing track and the voice is the lead, but most of the tracks don’t feel complete without vocals.

Grundik Kasyansky: “It’s perhaps a lazy comparison, but the way Gosha works, is very similar to Damo Suzuki I think. He uses the voice in a rhythmic more than a melodic way.

GH: “One of the problems I have with vocals is the meaning of the song. Once you go more abstract, it frees you to do whatever you want. If you want to scream, you scream. If you want to chant, you chant. The moment I don’t have a message to give the listener, I get this freedom. The music we make is dark music, it’s not happy, it’s existential, but this is something that needs to be put into some form. I can’t do it in a literal way. I approach it in an abstract way.”

How do the sound and visuals connect in the live sets?

Danil Gertman: For me, the most important thing in live performance is atmospheric fulfillment, when the visuals and images are combined with the sound. I feel like I’m just one of the musicians, but instead of music, I paint a picture.

Do the visuals influence the music?

DG: It should be an influence, the band are playing facing the screen, not with their backs to it. I told Gosha: “If I’m going to be involved we’re sitting and looking at what we’re doing together. I’m not making visual backgrounds. It should be collaborative.”

GK: Influence isn’t the right word maybe. It’s like the equality in an orchestra, how one violin connects to another violin. It’s supposed to be the same, to be one thing.

GH: When we play live, we don’t do songs. We do a long piece. It’ll be a story, sonically and visually. The idea is to have one piece of work. The visual isn’t there to illustrate. It’s part of the story.

Most of your albums originate in live sessions. Is there something you think you can only get by documenting live performance?

GH: I used to go into recording sessions thinking about songs, and how best to do it. On Kadita Sessions we realised the most important thing is to create an environment for everyone to enjoy themselves. From then on, most of the effort has gone into looking after each other, making sure everyone is having a good time and really going for it. There’ll be time to think about structure, individual tracks, how it’ll all work together, later. Now, let’s document the great time we’re having, the intensity there. If you start rehearsing, going methodologically, you lose something.

Maya Pik: For me it’s not a documentation in a documentary sense. We’re capturing something almost impossible to capture. The small gaps between time and space which don’t really exist, where it’s always changing.

GH: It’s just not music, it’s something you can’t describe, but sometimes you can capture a bit of that feeling.

Ran Nahmias: It’s more like capturing your state at the time. I think capturing failure is also important with that. If you’re falling down, sometimes documenting that is more important than capturing some glorious, rehearsed moment.

Maya is credited as playing a rocking chair on Inwards Opened The Floor, and, you all play unconventional instruments. Can you talk about how that started?

MP: The rocking chair came out of another project, but then ended up in Staraya Derevnya. We made the rocking chair smaller, for practical reasons, and that changed the sound again. A big part of Staraya Derevnya is taking fragments of different things that have worked elsewhere. I think that’s what a lot of us do.

GH It’s not a conscious decision. I try to just think about the sound. If you go to a music shop and look for instruments, there’s a selection that sounds nice and clean, you get what you pay for. But if you go to a toy shop or a market, every single one will sound completely different. They have their own quirks. You can play each one until you find something you like the sound of. You don’t get this with conventional instruments. You play around with something, and then you hear how it could fit in a track, and you’ll know there’s nothing that would sound better there.

MP: In ‘Gallant Spider’ [the final track on Boulder Blues] there’s a recording of my kids playing with a drum machine. Like Gosha’s toys, it eventually ended up in the right place.

Ran, how did you end up building your own cello?

RN: Cellos are big, and if you put one on a flight, you’re worried if it’ll survive the journey. Some musicians buy a seat just for the cello – that’s cute but it’s expensive. So, I broke down a cello, I took out as much as I could, so all that’s left really is the neck. In Hebrew we call this the soul of the cello. We took the soul and it became a different monster. It works a bit differently to an electric guitar. It’s not taking vibration from the strings, it’s not electromagnetic amplitude. It’s the sounds of the wood itself.

Staraya Derevnya often gets referred to as psychedelic. That word gets used a lot now, what does it mean to you?

GH: I have this analogy, it’s something you fall through. For me psychedelic music, it’s this sensation of falling through the music. If you listen to this music, you know what I mean, it’s the way you perceive the music, the way it takes you inside, how it consumes you. I hope most of the stuff we do is that in that dimension.

GK If you want to compare it to an art movement, I think surreal makes more sense than psychedelic. But then, even surreal is just another word…

MP: We all see things differently. I actually think the misunderstanding is a big part of it. I think it’s good when people hear music, sometimes they don’t understand what’s behind it, or in the same way we do. It’s open for them, and for us, its meaning can change and evolve.

Miguel Pérez: How music and the environment gets into your brain is one thing, but the way you get it out of your system, is different. There’s not a specific language, you can put your own language into it. It’s familiar, but it also lives in its own world.

Boulder Blues is out now on Ramble Records, find out more and purchase it here. Miguel Perez’s music as Skull Mask can be heard here