Arriving in 2002, The Books’ debut album Thought For Food found a Western world on the brink. It was a 2002 still reeling from the events of 9/11, but one in which the Department For Homeland Security wasn’t yet operational. It was a 2002 not affected, despite many people’s fears, by Y2K, but one that played host to a hint of terrors to come, like the first ever case of SARS and the founding of Friendster (a social media forerunner of MySpace and Facebook). To put this liminality in perspective: roughly 50% of the US population owned a mobile phone.

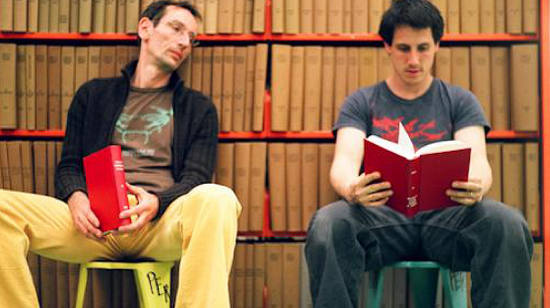

The Books were a duo comprising Nick Zammuto (intense, earnest, never far away from talking about “amino acids” or “infinite grids”) and Paul de Jong (quiet, donnish, the air of a venerable physicist). They made four near-incomparable albums that took in folk, sound art, electronica, but strayed into unlikely genres like post-rock, glitch, and IDM almost by accident; they began with Thought For Food.

Though they were, and remain, a quietly popular group, The Books as a project seemed designed not to set the world alight. For a start, their name is an SEO strategist’s worst nightmare, and their albums were difficult to adequately categorise without being either prolix or vague. These concerns, though perhaps included glibly, were significant with the growing prevalence of Google and online streaming sites.

The Books’ music is quietly cerebral, using a palette of loose collaged acoustic instrumentation, found sound, and alien electronic processing. It seems fitting that The Books sat down while playing live, such is their studious, considered air. Even the age difference (ten years) between the members seems off-centre. Bands would do well to look similar, like they’re part of a gang (see The Libertines, The Spice Girls, Black Rebel Motorcycle Club, etcetera), but The Books seemed dislocated from this. Your typical noughties band press shot would have The So-and-so’s squashed together, glowering and gurning down the lens, whereas The Books might be looking in different directions, doing different things with their hands, slightly apart, as if embarrassed to be together.

Despite their inherent knottiness, Zammuto and de Jong managed to create one of the most unique sonic formats since Suicide – that other New York duo with a noticeable age difference, heavy reliance on the possibilities offered by machines, and ability to create some serious atmospheres; though if Suicide’s music evoked the late 70s: red-lit nightclubs, amphetamine, and liquor, then The Books evoked the early noughties: day-time TV, diet pills, and flat tummy tea.

A fin de siècle, a changeover, like the one between the 20th and 21st century, can be a strange time. Sally Ledger and Roger Luckhurst write of the classic fin de siècle (between the 19th and 20th century) that “this was an era of extraordinary technological advance… and yet it was also an age of very real decline”. Not only might we also apply this definition to the turn of the 21st century – for instance the International Human Genome Project had mapped a rough draft and made it available for free online, but HIV/AIDS had created a mediaeval-style panic and subsequent retribution just a few years before – we could also apply it to music made in this period. The popularisation of computers in the West meant most types of music became far easier to make – traditional recording methods just didn’t come close to the level of control afforded by a DAW (digital audio workstation). However, much of popular Western music was declining in terms of adventure and forward-thinkingness; consider The White Stripes’ bluesy workouts, The Strokes’ wretched Velvets-aping jingles, or… well, Creed. As well as rock, Tom Ewing writes in a noughties retrospective for Pitchfork that “every week brought some R&B or teen-pop or commercial hip-hop single with a new angle on pleasure”.

In his excellent FreakyTrigger blog, Ewing related the 1998 release of ‘Blue’ by Eiffel 65 to how “people were gearing up for an especially huge party season, with a certain amount of overwrought concern about whether the world would come out of it alright” and that “forced jollity and global sing-alongs were on the agenda”. Thought For Food seems a natural reaction to “global sing-alongs”, Thought For Food seems a total opposite of Eurodance. The Books’ rich gumbo of gnomic spoken word samples and strange grooves (Paul de Jong said of the Books’ philosophy that “there’s percussion everywhere”) anchored by guitars and cellos moulded into mosaic-like patterns is characteristic of this time. The music personifies something technologically proficient but rigid and clunky like a brick phone, or queasily nostalgic but profound, like shaky video footage of a historical moment.

Whether the art made during genuinely liminal times actually expresses the spirit of the age, or retrospectively mapping it this way is more useful, Thought For Food can be thought of as one of a number of artworks that perfectly embody the turn of a century. Ramsey Campbell speaking in a Quietus interview says of the composer Gustav Mahler (active during the original fin de siècle) that “he’s got one foot in the tradition and very much straining the other foot into modernity”, while Austin M. Doub writes that he “incorporated elements of both past Germanic traditions and modern ideas”. In the same way Mahler used cowbells to evoke a nostalgic past and incorporated folk music while also pushing the boundaries of progressive tonality, The Books use traditional instruments – cello, acoustic guitar – and process them to excess, with strange, otherworldly samples sitting cheek-by-jowl with more traditional vocal choruses. A liminal age demands liminal art. Social cycle theory suggests that history is just a cycle, which is why it’s interesting to note the similarities between various century changeovers.

These differing states – as relating to Campbell’s idea of Mahler’s feet being in two opposing camps – include in fin de siècle art nostalgia and optimism, tradition and future, and the rudimentary and the sophisticated. These can all seem at war with each other in Thought For Food. Listen to the way the glitchy gobbets of electronic noise and the deadened guitar strings seem to fight at the end of ‘All Bad Ends All’, with each element reeling, staggering, and ducking as if trading blows. What’s more, the effect of the fighting is a literal explosion noise followed by a short orchestral coda that interrupts rudely, as if saying ‘remember me?’. Likewise, in ‘Deafkids’, jazzy piano chords dance with a tinny digital squelch sound, before a sample intones ‘silencio’, and a huge splintering snarl seems to envelop the whole track. Moments like these evoke alternate states in combat that can eventually become too much to take – clearly the centre cannot hold.

This combative atmosphere leads to the strange and slightly anticlimactic track listing – perhaps the worst thing about it. On a bad day I’ll say the album is top-heavy, but on a good day, I’ll say it represents a kind of musical disgregation where the substance gets weaker and weaker as a result of the energy expended in the early tracks, like the limber, dynamic arrangement in ‘Enjoy Your Worries…’, or the demented speakeasy rollick of ‘All Bad Ends All’ and ‘Thankyoubranch’. For instance, the penultimate track, ‘A Dead Fish Gains The Power of Observation’, is a minute-long spoken word piece over some trickling water sounds; it stands at odds with those hectic, dense, emotional cartwheels in the first half of the album.

The sense of music stretched thin means there’s a perceptible nervous energy to some of the songs, perhaps a leftover from Ewing’s idea of people worrying “whether the world would come out of it alright” and partying. Listen to that manically-played fiddle in ‘Enjoy…’, or the vocal sample of the child laughing in ‘All Bad Ends All’, or a syncopated percussive rhythm on ‘Thankyoubranch’ that seems to almost fall over itself in the rush to hit each beat, sounding like a prefab rhythm track that has accidentally replaced a full drum track. Indeed, the very content of the sound – the junk shop, kitchen-sink, overload of sonic bric-a-brac feel, the strums, thrums, clacks, clunks, and breaths of it all – is an almost carnivalesque free interaction between old and new sounds. When it’s not painstakingly constructing spidery structures of sonic filigree, Thought For Food can be totally joyous, beautiful, and fun,

This giddiness extends to moments where the machines appear to take over, like the deadened guitar strums on ‘Enjoy…’ (too fast to be played by human hands), or the way the bass riffs in ‘Mikeybass’ are moulded and sculpted by the electronic treatments like its plaything. These organic instruments are almost pushed too far; here, rudimentary material interacts with machine sophistication. In the same way that the fin de siècle played host to questions about the role of the author, with a literary movement like Realism where speculation is avoided, an important question to tease out with Thought For Food and the 20th century fin de siècle is the way that art can be seen to create itself.

When Mahler was writing his Symphony No. 3 he told a friend that “the torrent of creation has proved to be an irresistible force”, and that it “has outgrown me and sweeps me along”. Like Mahler being swept along by the force of his music, The Books often find the genesis of a song in a single sample then let it guide the way. In the same way pillars of society like imperialism and popular religion were, though not disappearing, showing early signs of fallibility, the idea of the Artist As God was also on shaky foundations. Fast forward another century and this idea had come to fruition with Brian Eno’s idea of generative music, the first rumblings of AI art, and Zammuto and de Jong’s discussing the “unexpected ways” their music goes, and how “a kind of critical mass is reached and the elements start to naturally build relationships and structures”.

Another pillar of society that always seems to be showing signs of weakness in century changeovers is trust in authority. Authority was questioned in a big way in the 1890s (see: the Dreyfuss Affair; growing disquiet over imperialism; industrialization leading to a decline of religion). This partly manifested itself in fin de siècle art with a tension between appearance and actuality that’s eventually, even inevitably, revealed. Consider Octave Mirbeau’s book The Torture Garden (1899), or James Ensor’s painting ‘The Intrigue’ (1890), which ostensibly depicts a happy crowd, but upon closer inspection it’s a cluster of masks with gaping maws and blank eyes (I can’t help noticing the similarity with the cover of Aphex Twin’s 1997 Come To Daddy EP – a title that also shares some of The Books’ queasy mixture of the homespun and the weird).

There are hints of these ideas about appearance and actuality in Thought For Food. The song ‘Motherless Bastard’ features a real-life recording of a father pretending not to know his young daughter at an aquarium. It’s clearly a cruel/abusive thing happening in a public place, then made even more strange by the wistful, countryfied, banjo-led backing – like the unmentionable acts that taks place by the “perpetual enchantment” of “shrubs, anemones, ranunculus and heuchera” in The Torture Garden. Parallels could also be drawn between this voice sample and the jaundiced, disturbing tenor of sketches in Chris Morris’ Jam (2000), where hatred and cruelty can often seem to be the very point, though couched in comfortable, domestic settings.

The Books seem to encourage you to question meaning. De Jong once said that “For us, the greatest collaboration is with the listener.” They want you to decide if it’s a shout of laughter or distress. or if that horn fanfare means a head of state has died or someone’s won a speedboat. Take the sample of Alan Watts saying ‘welcome to the human race, we’re a mess’ from ‘All Our Base Are Belong To Them’. This isolated quote could be seen as a positive or negative thing, a sense of warts-and-all unity or just gloomy dismissal; it’s an idea that cycles back to Ledger and Luckhurst’s quote about “technological advance” and “real decline”.

The Books aren’t putting forward any clear political arguments, but their songs do give a sense of the uncertainty creeping into an increasingly connected world. Like the image of Lizzie van Zyl used as propaganda in the Boer War (1901), or the Nayirah testimony (1990) that formed part of the basis for the Gulf War, the bewildering array of vocals on Thought For Food are often stripped of any context whatsoever. The Ulysses-esque blaze of different voices spool forth between languages, pitches, accents, tones, timbres, with little background, and with no clear meaning, like an audiobook of a Tik-Tok timeline. Perhaps you could even see this surface appearance and hidden actuality comes across in the way that tiny snippets of sound are totally repurposed. The hundreds of percussive thuds, clicks, and snaps that litter the album could be taken from anything: flesh on metal, wood on rubber, plastic on membrane. This idea of perception is a huge part of the century shift, and of the Books’ music.

This was clearly something in the water in the West in 2002, especially in New York. Walter Lacquer highlights a condition of fin de siècle art as “cultural pessimism”, or the worry that nothing new can ever be again created. We see this idea in other landmark experimental music released in America circa 2002. There was LCD Soundystem’s misanthropic ‘Losing My Edge’ where James Murphy runs his well-worn rule over nostalgia and originality. The Books evoke that song’s superb line: “I hear that you and your band have sold your guitars and bought turntables / I hear that you and your band have sold your turntables and bought guitars”. William Basinski’s Disintegration Loops comprises various single samples decaying over time. Likewise, one of the most prominent hooks in the entire Thought For Food album comprises Zammuto singing “I was born on the day the music died”, over lazily-strummed, resonant, rumbling guitar chords. All these works are actually very forward-thinking musically, but the spirit of pessimism is the important takeaway.

Though fin de siècle art (of which we can consider Thought For Food a part) is made in the run-up to the turn of the century (the time frame for the classic era is 1890-1900), The Books instead document the effect of the turn of the century. If art from the traditional fin de siècle timeframe, from the run up to the end of the century, seems to ask ‘what’s next?’, then the art directly affected by the turn itself asks ‘what now?’.

Indeed, in the same way that other fin de siècle classics like Heart Of Darkness or The Strange Case Of Dr Jekyll And Mr Hyde could only have been made when old gods like imperialism and trust in authority were beginning to show early signs of weakness, Thought For Food was an album that could only been made at the turn of the 20th century. For one, 2002 was a time that made possible an ironic distance from self-help videos that The Books plunder for their samples. There was also a timely interrogation of ideas about mindless content consumption – see ‘Read Eat Sleep’ – and millennial anxiety – see ‘Enjoy…’. Furthermore, the technology needed to create their dense structures (some tracks reportedly consist of up to 150 distinct samples) of foley percussion and loops could only have been done on a DAW – the means just weren’t there before the 20th century. It’s interesting to note that both The Books and Burial (who started making music at a similar time) made their music on SoundForge, a program where, instead of having the traditional arrangement of individual tracks, you mix and layer each track onto the next, like a midpoint between the old idea of ‘mixing down’ a track on a console and modern DAWs.

The Books never seemed to deliberately make something that summed up the spirit of the age, but chanced upon the creation of an album that gives us a hazy idea of the very early noughties, and everything that came with it. Thought For Food is the sound of a thousand home videos running in parallel, of the mindless wave of information that came with the internet taking baby steps towards world domination, the trickle of data that would become a rushing tide, all the cynicism and optimism, all, as The Books sing in ‘Getting The Done Job’, ‘the sounds of single people doing nothing’, blinking in the grey light of a new century.