When you write a book about something you’re obsessed with, your relationship with that thing, with the stuff of it, doesn’t stop when the book is published. That subject gets a second life: one in the world, where its readers pick up where you left off; where a layer of complexity is added as people respond. Submitting the PhD on foghorns; starting the manuscript on foghorns; finishing the book on foghorns: they might seem like moments of completion, but they are not. They are high water marks in the lifecycle of my relationship with this subject; with this sound, which continues even now. They are moments when I said "I’m finished", but this thing has a long tail that keeps growing.

People send me their stories of sounds they remember; of foghorns they have known. I am a keeper of these memories. The remoteness of the sound, its existence into the past and its continuing use in music, film and TV mean that people have their own knowledge about this sound. The remoteness of it, combined with the subjective experience of sound, mean there are fragments, tangents and previously untold stories emerging all the time.

The paperback is out now, and so I’ve compiled some of the ephemera that has gathered since publication, from folklore to personal stories; from rattling latches in the North West of England to silenced horns in Kathmandu.

My mum told her mate Dave about my book. Until fairly recently Dave was a park ranger at Werneth Low (a hill in Greater Manchester) where he used to rally his devoted clutch of volunteers by reciting poetry/Shakespeare as they lay hedges and picked litter. Dave now lives in what used to be a mill, and there is a stream running out the back of his house, where he sits to read, write, and listen. He wrote me a letter from this spot (apparently while feeding a blackbird by hand) about how sounds had patterned a spirit in the house he used to live in. All the doors had latches on, and he wrote that: "In easterly winds one particular door rattled from October to March … I grew accustomed to this over the years, and felt this was the sound manifestation of the spirit of the house. It only happened in the autumn and consequently felt alone during the spring and summer. In the first gusts of autumn, when the easterly wind racked the building, sure enough, there was the rattle, and I would call out loud: ‘Oh, you’re back!’. Silly really, as there was no-one there, but I began to feel somehow, that that sound represented a returning, and I felt I should at least welcome it back."

I wrote about a number of stories from myth and folklore, one of which was from Cornwall, that says that the sound of the battle of Tintagel is still reverberating under the waves. More folkloric stories of sound have emerged since I finished writing. In the highly recommended Reader’s Digest compendium Folklore Myths and Legends of Britain, there is mention of The Whooper of Sennen Cove. The whooper whooped from under a heavy mist, which would blanket the cove even on a clear day. It was known to predict bad weather and stop fishermen heading out if there was a storm on the way, but stopped whooping when two men who were particularly determined to get out fishing, "beat their way through the mist with a flail". Neither was ever seen again.

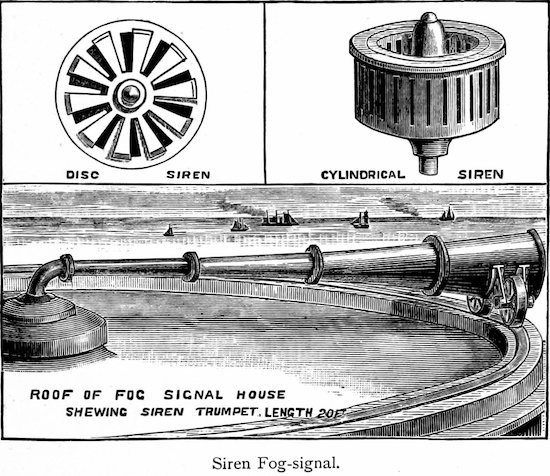

John Tyndall was the Victorian scientist who conducted the first large scale foghorn testing sessions in the UK, honking for months to find the best foghorn. He did a lot of work on acoustics and the air, some of it around this experimentation with colossal coastal sounds, and the strange ways in which the atmosphere and the landscape, would toy with his monstrous horns. He also, once, showed his foghorns to Queen Victoria, as mentioned by Roland Jackson in his exhaustive biography of Tyndall, and an engraving from 1876, now in the archives at the Wellcome Collection. Queen Victoria, was evidently not particularly impressed with the demonstration, only remarking in her diaries on how ugly Tyndall was.

I bought a cassette recently, a tape I wrote about in the most recent Rum Music, with one side that contains a recording of car horns at an intersection in Nepal, recorded by Shun Nakaseko in 2010. The other side contains the recording of a lone cricket chirruping alone on a boat trip. The label sent a note with the tape saying they had read my book, that they lived on the west coast of Ireland and often went swimming in the sea (but that it’s still too chilly – the sea holds onto winter chills much longer than the land). I realised that the tape – like the coasts I wrote about – contained a lost sound. Foghorns were turned off in Ireland many years ago, for the most part. The car horn symphony on the tape is also a soundscape that is now lost, after a horn ban was implemented in Kathmandu in 2017.

Anne Carson has a poem about Red Desert, the Antonioni film starring Monica Vitti. In it there is a scene where the group drives to a cabin at the end of a pier in a dense fog, where there will be a confusing sort of orgy. In the scene, and in the poem, the foghorn sounds. Carson writes: “A foghorn sounding through the fog makes the fog seem to be everything.” I mentioned it briefly in the book, but its significance remains obscure to me. Is the foghorn a symbol of Vitti’s unravelling, or is it a warning to her from the fog, against going inside?

Loren Connors is best known for his guitar work, but between 1985–87 he stopped playing and wrote instead. His prose poems are short paragraphs, diary entries with haikus instead of full stops. These were (re)published fairly recently as Autumn’s Sun, a quiet book that contains in its prose a simplicity and a stillness that I find in Connor’s music, and that I am often looking for in life. When these diary pieces were written he was living with his partner and young son in New Haven, Connecticut, and the lighthouse, the beach, the sea are places from which he writes his plain, perfect scenes. On July 25th, he writes about new houses being built on the shore in a place called Branford: "They’re big and placed apart from each other, but I guess the people’ll all hear the same cars pass and the ocean horns over the fields."

In The Foghorn’s Lament, I talk about someone called The Fogmaster, who apparently used to do guerrilla foghorn performances. A few years after I first messaged him on Facebook and six months after the hardback came out, he replies. This is completely out of the blue. He says he’d love to talk. I message back to arrange an interview, start prepping a pitch for where to publish this thing that only I realise is significant – finally this lost musician; this forgotten performance artist; this lone post-Fluxus agitator; this radical sound artist – he still exists! He’s willing to talk! I reply twice to arrange an interview. He does not reply. I start to wonder if he is an echo of my own obsession, bumping into sonic energies suspended in the air. Or perhaps he’s just crap at email. His inbox might resemble mine: a skip fire. Maybe in three years he’ll surface again, and we’ll have that chat I’ve been chasing. In the meantime, his ringtones are still available.

The Foghorn’s Lament by Jennifer Lucy Allan is published by White Rabbit Books