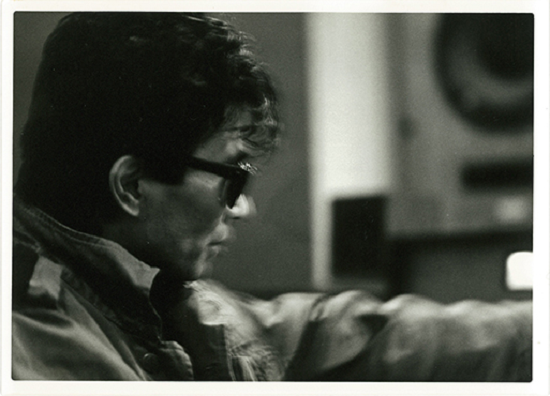

Vanity Records founder Yuzuru Agi

While the punk movement was shaking up the world in the late 70s, a single record label in Osaka, Japan set themselves up as one of the country’s first independent labels. Vanity Records was exceptionally mysterious in their short-lived activity between 1978 and 1981, experimenting with emergent electronic equipment in order to pursue dark dystopian sounds of their own. As secret experimental pioneers, their monochromatic fuzz grated against the glossy sheen of Japanese pop culture through an anonymous agenda.

In fact, even before the sound of the Japanese 1980s came to be associated with the synth bleeps of Yellow Magic Orchestra, Vanity’s founder Yuzuru Agi was the first to coin the term ‘techno-pop’ in August 1978 in Vanity Record’s own publication Rock Magazine. With the recent re-release and re-discovery of Vanity’s discography 40 years later – posthumous to Agi’s death in 2018, long after most people associated with the label had branched off along other paths – its sonic shadow reaches out towards today’s attentive ears, a pleasurable shock despite their coarsest resonances.

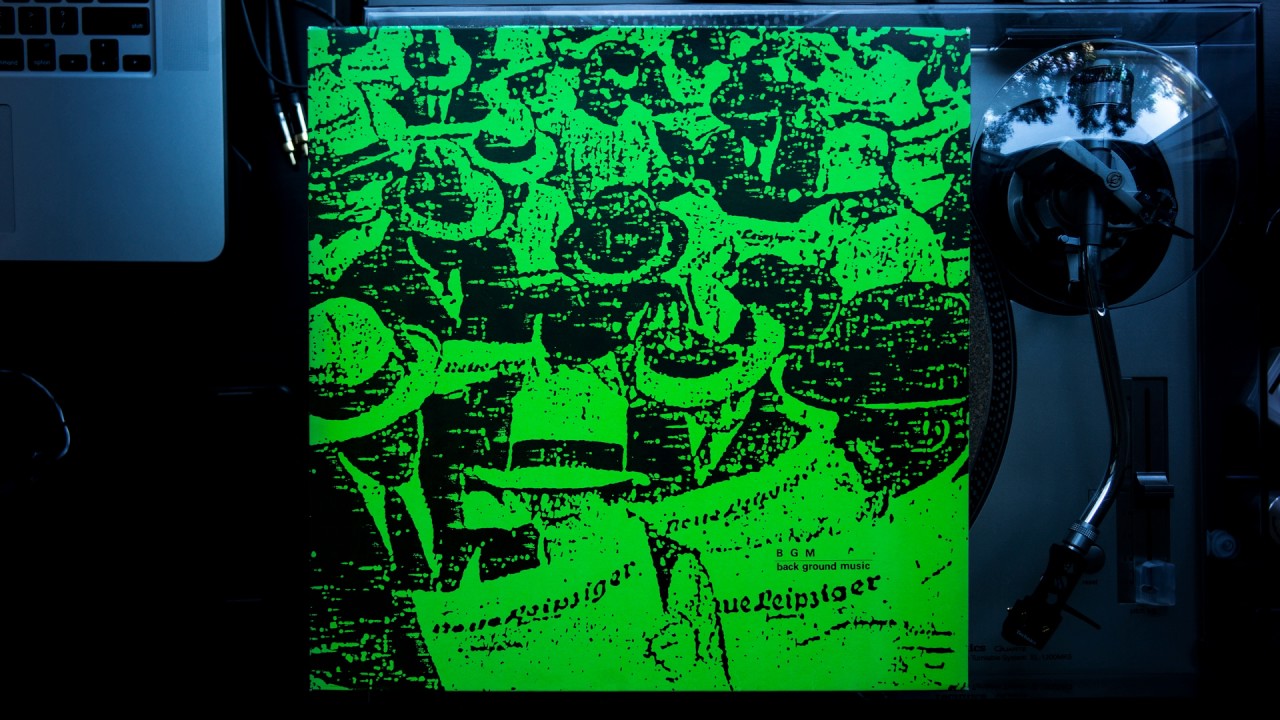

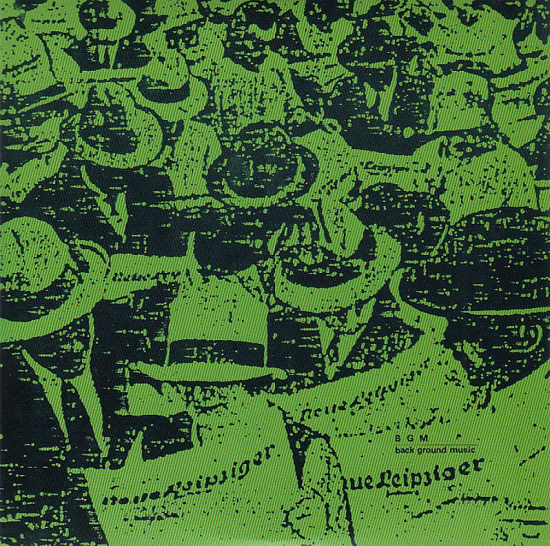

The spectrum of styles blurred in noise – post-punk oddities, gritty new-wave, minimal-synth and ambient radio noise experiments – rings alluringly to international diggers who encounter a singularity even amongst a wealth of coveted Japanese re-releases. The label existed for only three years and the identity of many of its musicians remain unknown, but each grainy record stands out as having an adventurous ethos. Albums like BGM’s Back Ground Music (1980) (released a year before Yellow Magic Orchestra’s BGM) foregrounds atmosphere itself rather than any specific figure or narrative. The tapes for R.N.A.O Meets P.O.P.O (1980), produced by a particularly mysterious group RNA Organism, were sent deliberately from London by airmail to feign being a foreign group. Amongst many arcane modulations created on analogue synthesisers, existential cries are also heard with guitars, such as on the recently re-issued corroded renderings of folk songs sung by Vanity’s head Agi.

Vanity’s discography captures a looming dystopia, a gleaming future made using electronics but then torn down in a fit ofpunk abjection. The label had appeared prophetically at the cusp of an important cultural moment – their crumbling soundscapes resonate with the cultural turbulence of post-war Japan, when Tokyo became the ground zero of a commercial explosion following an economic miracle and tech boom, and when recently omnipresent traditional surroundings were being replaced at an alarming rate.

Encroached by a totally mechanised society, Vanity’s sounds

using newly available monophonic synthesizers, sequencers and drum machines revel in fetishistic treatments of noise,

ringing deadpan with the discomfort at society’s underbelly. The metallic ambience of TOLERANCE in albums Anonym and Divin addresses our mutated psyches, savouring an artificial world with sensual echoes. Sympathy Nervous fixate on cold, broken synth bleeps using a mysterious original invention for their compositions, a computer they programmed themselves called the U.C.G. (Universal Character Generator) alongside a theremin. The atomisation of Japan’s white-collar worker demographic is portrayed with a foggy minimalism in SALARIED MEN CLUB’s white noise experiments, sounding

like a musical equivalent to Shinya Tetsukamoto’s cyberpunk horror-film Tetsuo: The Iron Man. The themes of modern

alienation that the West have explored are sharpened in sound and heightened in resonance, with an outlandish obscurity as alluring as noises from a distant world. Especially amidst the catastrophes our own technological age, Vanity’s apocalyptic music casts an ominous fate, calling out to listeners in the 2020s from the past.

In a world of informational abundance, the hazy idiosyncrasies of their music perhaps acts as an appropriate placeholder for the unknowable – especially to the West, where its strangeness reverberates with existing fascinations.

Particularly since the 1990s, there has been a tendency to assign Japanese musicians using extreme levels of feedback and distortion under an umbrella. The media flow of musicians whose styles were abrasive then – Boredoms, Merzbow, Incapacitants or Hijokaidan – had caused expectations of an intelligible ‘movement’ in Japan when in fact these musicians themselves – as quoted in David Novak’s Japanoise: Music At The Edge Of Circulation – have personally claimed they do not necessarily relate to each other at all.

Whether or not any aspect of noise is inherently Japanese, an idea of this was created and sustained in a feedback of

information from East to West. In the same way, the delirious sounds made by Vanity Records must have surfaced from what felt like a great distance towards international collectors, who themselves had navigated a chaotic sea of material before arriving at what felt promisingly unique. After all, due to Japan’s long history of adopting Western influence, their eclectically ‘Japanified’ foreign tastes have been made into a satisfying catalogue of ‘re-issues’ for the West – held up as intriguing mirrors, except the distortions of which are construed by essentialisms, perceived myths of Japanese ‘uniqueness’ which are fed back to Japan. The buffer of information between the two – existing historically due to geography and linguistics, and more recently due to the effect of media bubbles – leaves out inherent context but leaves idealisms intact. With a label as brilliantly peculiar as Vanity then, it feels important to delve into immediate circumstances before feedback shrouds things further.

R.N.A.O Meets P.O.P.O, 1980

With its wide range of styles united by a particular aura, it could be said that the lack of any specific colour to Vanity’s discography was due to the creative directions of its founder, the influential music critic and charismatic producer Yuzuru Agi. Agi was passionate and wildly eccentric, apparently having a brief stint as a ‘Kayoukyoku’ idol (Bluesy Japanese pop music) in the 1960s. Electrified by San Fransisco’s underground rock scene in the early 1970s, he followed by organising avidly attended concerts – whose line-ups included notorious cult-band Les Rallizes Denudes. He started up his own fashion brand as well as commencing a career as a regional radio DJ. But most importantly, prior to the establishment of Vanity was the emergence of Rock Magazine, Agi’s own elaborate publication which attentively followed the movements of Western counterparts but ultimately bolstered the work of his own musicians. Inspired by new indie labels of the UK which radically embodied the mood of a generation – like Rough Trade and 4AD – Agi ardently pursued the ‘now’ and allowed an array of musicians to gather indiscriminately under his taste.

Agi’s Rock Magazine had legendary status for many engaged listeners in the 70s and 80s. When Japan’s domestic scene was dominated by idol culture and the spectacular influences of American pop or stadium rock constituted ‘foreign music’ for the public, Rock Magazine delved into gritty post punk, granular minimalist electronica or deviant new wave coming from Europe’s underground. The publication brought information about Western genres in painstaking detail, charting the German avant garde from Mahler and Schoenberg to Kraftwerk and CAN, and

introducing Brian Eno’s ambient work in Japan firsthand. It aimed to educate a Japanese audience in the language of Western youths, initially incorporating the more playful elements of manga culture before increasingly honing in on leading-edge British bands: Joy Division, Throbbing Gristle, Bauhaus and Wire. The only one of its kind in the Kansai Region and outside of Tokyo’s crowded mediascape, the magazine was a beacon observing waves of shock from the West firsthand, absorbing the aesthetics of punk or the radical deadpan of electronica. Rock Magazine reflected a lively curiosity with its format changing constantly like a punk zine, often attaching flexi disks inside of their issues. Its changing art style experimented with its own design and was printed in different sizes, colours and material,

sometimes even having holes cut out in pages to trouble the bookbinders and shops which dealt with them. Its unique

perspectives imbued Agi’s vision who invented original names for genres, denounced the outmoded and criticised passive consumption. The first edition announced, “From now on, I want you all to pursue what is truly meaningful, purely and surely. Think of this book as a fun ‘textbook’ for you smart ones.”

Rock Magazine

Obsessively embracing previously unheard sounds arriving from abroad, their hypnotic qualities were overwhelming, almost amounting to a religious adoration for Agi who used his own concoction of music and media to seize it. In an interview with Hanagatabunka-tsushin, former Rock Magazine editor Kanomi Mikihiko explains, “The magazine was about resounding with the feelings of a generation, or in other words, using music to unravel the time of an era.” The rush to take part in the moment happening far away meant interpreting niche foreign genres rapidly to a

context where it would have been otherwise hard to conceive.

Thanks to an employee of theirs based in the UK, probably among the few Japanese people who were able to catch bands like Throbbing Gristle and Bauhaus during their original lifespans, they were able to swiftly keep up to the explosive wave of genres that were being discovered at each moment and report scenes as they happened. Rock Magazine apparently had a high turnover of its staff members since the speed to which cutting-edge information was demanded: immediacy was key in being contemporary. Most content was dedicated to introducing Western artists, filtering out avant garde players within an opaque net of information. After all, many Japanese punk roots aped the West. The cult-favourite Tokyo band Friction echoed the New York Dolls or The Ramones. Les Rallizes Denudes suggested The Velvet Underground.

Tetsuo: The Iron Man (1989), regarded as the quintessential Japanese cyberpunk film, was influenced by Sogo Ishii’s dystopian punk rock musical Burst City (1982), whose Sex Pistol-like stylistic references directly reflected Derek Jarman’s Jubilee (1978) or Julien Temple’s The Great Rock And Roll Swindle (1980). Vanity exists within this larger history of Japan’s adaptation of Western influence, and in their case it was the sleek solemness of despondent post punk and experimental electronica.

B.G.M.’s Background Music

Promoting sounds which variously embodied the void and discord, Japanese artists releasing on Vanity were introduced in the same light. In the case of the kind of foreboding post punk and industrial electronica that Vanity championed, an inherent futurism probably intensified ambitions. The flourishing experimental styles of the West made sense for Japan’s disillusioned members after a turbulent modernity rapidly outstripped traditional identities, and the transition towards a cold, mechanical world was aided by synthesisers, just as Japan’s electronics industry produced Yamaha, Roland and Korg. Having closely studied the recent revolutions of Western subcultures, or the nascent world of electronic music, the thought of engineering a moment of their own appeared tangible. Satoru Higashiseto, who later acquired Vanity’s archive adds: “I can’t deny the cultish aspect of it”. Yukio Fujimoto, a sound artist who previously

released on Vanity as Normal Brain, <a href="http://studiowarp.jp/kyourecords/vanity-interview%E2%91%A6-normal–

brain%E8%97%A4%E6%9C%AC%E7%94%B1%E7%B4%80%E5%A4%AB/" target="out">made a comparison of Agi’s team to the doomsday cult Aum Shinrikyo.

The overt zealousness of Agi’s pursuits caused doubts for Hitomi Moritani, today known for her ongoing solo project in experimental electronica, as Phew. She was involved with Vanity only on one occasion with her avant garde post punk outfit Aunt Sally, releasing the self-titled Aunt Sally in 1979. Despite the label’s cultivated obscurity her release had a striking presence, her vocals cutting through dissonance to deliver a cunning pastiche in no wave minimalism. A piece in Rock Magazine in September 1980 introduced the curious escapism of her lyrics, set against a dark urban setting of vagabonds and faceless crowds – “I want to pursue dreams, even if its an illusion… the sounds of Aunt Sally are probably more suited to me now than Brian Eno.”

But to Moritani, the entire procedure was impulsive. She encountered Vanity, the only label of its kind in Osaka, reading Rock Magazine in her middle school days, a prime source of information. As soon as her band formed, a demo tape was taken to the label who decided its release on the spot. “It wasn’t so much

about being successful or validated than being a part of what was happening,” she recounts in an interview. “In the UK, teenagers would form bands and release singles to say, ‘This is our generation and we’re going to shape it.’”

But instead of casual spontaneity, a visible adherence to models offered Western subcultures eventually caused disagreements. “I stood in an opposing position to Agi, who wanted to produce us as artists. It was a time when the idea of a ‘manager’ pulling strings behind a band gained traction, since Malcom McLaren used media to turn punk into an international movement. I think Vanity was interested in doing the same thing. After one album, I refused to have my work treated as content to be ‘consumed’”, says Moritani.

One particular episode reveals the all-consuming influence of Joy Division, when Moritani was in Vanity’s studio during a recording session by the famous folk singer Morio Agata. Agi played Agata Unknown Pleasures, urging him to mimic its phrases in order to revamp his traditional sound. Rock Magazine had in fact been the first to introduce Joy Division to Japan – Agi, who was responsible for the Japanese translation of some of their liner notes, was the only Japanese critic who responded to Ian Curtis’s death contemporaneously and seriously. The radical emptiness of their music, seemingly wiping all into a blank iron slate, chimed well with the magazine’s readers – Moritani herself was deeply impacted when exposed the psychic weight of Curtis’ vocals, sealed into the radical simplicity of the Unknown Pleasures sleeve design. Yet when Agata promptly followed Agi to copy their riffs, Moritani was disappointed and promptly decided to leave the studio.

Vanity’s creations invite intrigue far beyond their own context, and their dismal punk and electronica cuts straight through into the skeptical 2020s. But their homegrown textures attempted to rationalise the irrational, looking into culture’s machine for clues. Part of its story that a foreign language group with surprising simplicity and severity was taken onboard with religious devotion. In spite of possibilities, in order to shake off the cumbersomeness of history, they turned towards a void. In Ghosts Of My Life: Writings On Depression, Hauntology And Lost Futures Mark Fisher wrote, ’If Joy Division matter now more than ever, its because they capture the depressed spirit of our times. Listen to JD now, and you have the inescapable impression that the group were catatonically channelling our present, their future. From the start their work was overshadowed by a deep foreboding, a sense of a future foreclosed, all certainties dissolved, only growing gloom ahead.”

Far away from Manchester, the shadow cast by the Second World War, the influence of J.G. Ballard and the backdrop of turbulent British politics at the dawn of the 1980s, the same foreboding future arrived in Japan via a different modernity to resonate amongst Buddhism and (anti-)Kawaii culture. Nihilism and melancholy were fashioned when the contours of neoliberalism informatics first made themselves felt, and while the extent to which aesthetic preferences were imitated are lost in noise, their mythologies amplify in informational networks. Ahead of their time nonetheless, yet it echoes in feedback without advancing towards a future.

Tolerance’s Anonym

Delving even deeper raises the question on adhering to music as an ideology. Agi’s dynamism indeed allowed his achievements to stand out. As Satoru Higashiseto says, “Whether as a magazine editor or a record maker [he] moved with his own impulse, often moving forward without careful consideration.” His sonic-fictions shared something to akin to Italian futurism, a fringe philosophy that took sound and technology as ways to mobilise the ‘spirit’ of a time. But as much as domestic circumstances, their answer to uncertainty was inspired by something arising from a distance,

relaying the same foreboding future to those who discover them today. What first appeared as a means to advancement in turbulent times regurgitated uncertainty as relics which mirror and reflect, confusing those who seek something different.

In her most recent work as Phew on Mute Records, Moritani has released New Decade. It’s a sombre dronescape painted in atmospheric layers, still using the noise of analog electronics but only as if to mourn futurist promises that were never kept. “Personally speaking, I’ve stopped being able to see a future that extends from the present.” Asked whether something like Vanity Records could occur again in this day and age, she replies, “perhaps there is too much information. Information travels further nowadays, but only to leave traces that immediately get forgotten. People pick and choose what they believe. Its harder to believe in totalising cultural movements, but I do see countless little pockets of micro-genres emerging everywhere. Maybe thats where the future is."