“A man does not recover from such jolts – he becomes a different person and, eventually, the new person finds new things to care about.”

F. Scott Fitzgerald, The Crack-Up (1936)

“I literally cracked up, went to pieces. I had a real attack of the Brian Wilsons."

Andy Partridge, speaking to the Fairfield County Advocate newspaper (1984)

By the time Swindon quartet XTC achieved some commercial success, for bandleader and frontman Andy Partridge it was already too late. It was a bad joke at his expense. He could not write a hit single if his life depended on it. The problem? The better looking, less complicated bassist Colin Moulding suddenly could. An instinctive show-off, Partridge had originally enjoyed touring, but was beginning to find it a traveling prison sentence, burning through his mental health reserves and making life unmanageable.

English Settlement, the double album which turns 40 this month, was Partridge’s solution to his XTC problem. It’s a highly ambiguous snapshot of Partridge’s relationship with his country. It’s a hiding-in-plain-sight masterpiece that, for reasons which will become apparent in this article, remains on the outside of popular consciousness. It’s also a grand folly, specifically designed to dig Partridge out of a particularly messy hole.

XTC would only once be on nodding terms with the zeitgeist. Their first two albums, White Music and Go 2, both released in 1978, didn’t quite convince in their role as part of the punk explosion. Their inherent zaniness delivering diminishing returns, Moulding correctly identified that the band risked turning into a second rate Talking Heads, whom they had supported across 1978 (“I sensed David Byrne was on the spectrum” remembered Partridge in a 2021 podcast, “I believe I am as well, so we got on like a house on fire.”) Moulding began writing with designs on the charts.

It’s here that the strange voodoo that exists behind all great musical collaborations began to alchemise. The better Moulding wrote, the more Partridge seethed. The more Partridge seethed, the better he began to write. Keyboard player Barry Andrews was sacked, and jobbing Swindon guitarist Dave Gregory – a man so committed to the pub rock dream he had literally been in a band called Alehouse – was introduced. Suddenly, across 1979’s Drums And Wires and 1980’s terrific Black Sea, XTC were a storming two guitar outfit with a pair of songwriters learning to compliment one another. Label and press attention was, however, flowing upstream to Moulding – who had written hits such as ‘Making Plans For Nigel’, which still defines XTC’s reputation in the UK, and ‘Generals And Majors’, a goofy disco rewrite of ‘Paperback Writer’.

If Moulding’s rising prominence threatened Partridge, then the band’s punishing touring schedule organised by Virgin was outright destroying him. Across 1980 alone, XTC played over 140 shows. 140 sound checks, 140 hotel rooms, 140 bad meals, 140 cramped van journeys, 140 bad sleeps, 140 disinterested press junkets.

“Let’s look at this scenario” explained Partridge to Rolling Stone in 2020, “you’re killing yourself by being worked to death. You are not seeing a penny for your labours and you’re starting to be really dissatisfied. And all those stories you’ve read when you were younger about so-and-so stars getting ripped [off], so-and-so stars getting worked to death. It was happening to us, and it was happening to me specifically.” Something had to give. What you do not do in that situation – what is generally agreed to not be an optimum course of action – is to decide suddenly cease taking Valium after thirteen years of heavy use.

The benzodiazepine sedative called Valium (now better known as diazepam) was first approved for UK prescription in 1963. By the end of the decade, GPs were scribbling over four million prescriptions of Roche’s new wonder drug annually. The Rolling Stones’ 1966 single ‘Mother’s Little Helper’ fixed a negative stereotype of Valium’s favourite customer in the public consciousness – the stressed suburban housewife. Over in Swindon’s Penhill council estate, Vera Partridge had been prescribed the drug in the aftermath of a traumatic family shock. Why not stick twelve-year old Andy – bright, eccentric and bullied – on the stuff too?

On one of XTC’s interminable US tours in April 1981, Partridge returned to his hotel room to find that his new wife had disposed of his Valium stash in a well-intentioned effort to confront his addiction. Partridge reacted terribly – the subsequent trashed hotel room being perhaps XTC’s sole concession to the rock & roll lifestyle – before reasoning that if he didn’t have a drug problem, then how could stopping possibly cause a problem?

But problems arrived in the form of panic attacks, depression, stomach ulcers, limb paralysis, chronic exhaustion and attacks of near total amnesia that could strike without warning. Partridge was already prone to low moods – the Black Sea album had been titled as an oblique reference to his emotional state during recording – but the Valium withdrawal manifested itself with an extremity little understood at the time. Caught in a snowstorm driving out of upstate New York, weeks into his withdrawal, Partridge remembered stepping out of the tour van to urinate in a field. Up to his knees in thick, white snow, he suddenly lost all awareness of who he was, why he was there, what his job might be. A blank horizon, a frozen borderline.

“I remember laying on the seat in the back of the van in the foetal position, sobbing quietly” remembered Partridge in Todd Bernhardt’s 2007 XTC book Complicated Game, “not knowing who the hell I was.” Like Joy Division only a year previously, here were the young men, desperately ill equipped to understand just what was going on with their singer, only a desire to get on with the job and the attitude of, ‘Well, aren’t we lucky to have this US tour lads?’ The singer’s repeated warnings to his band, his management and Virgin Records went largely unheeded. At the end of June 1981, the band were finally permitted some time off.

What Partridge needed was a plan. What if he could deliver an album sufficiently complex that there would be no need to tour it? He rented a quiet room above a shop in Swindon town centre to write, looking out at Swindon around him with the renewed focus of a mind coming out of the cold.

The sessions for what would become English Settlement began at the large, residential Manor Studios in Oxfordshire on 5 October 1981. There would be no overbearing producer, only the band collaborating with Hugh Padgham, who had engineered under Steve Lilywhite on their previous two records. “They had quite a clear idea of what they wanted” explained Padgham to Record Collector in 2010, “and I just made sure that this could be translated as easily and as clearly as possible.”

Though this would be hard to detect from the bulk of XTC’s prior output, Partridge had a sophisticated understanding of the musical avant-garde. He had spent the early 1970s devouring Phillip Glass, Sun Ra, Beefheart, Steve Reich, Can and weird jazz – once describing jazz and novelty music as the twin poles of his creative life. Any surplus studio time would be devoted to his experiments – filling b-sides with ambient pieces, even recording a dub version of their second album Go 2. In 1980, he contributed to Yellow Magic Orchestra alumni Ryuichi Sakamoto’s minimalist electronic masterpiece B-2 Unit. There’s an umbilical cord of tracks in this vein across XTC’s early records – ‘Complicated Game’, ‘The Somnambulist’, the pulverising ‘Travels In Nihilon’. Given the freedom to effectively produce English Settlement, Partridge began working these ideas further and further into XTC’s sonic palette.

The six weeks at the Manor would be remembered by band and producer as some of the happiest of their lives. Ardently anti-drugs, the band would unwind with warm ale and long games of conkers as the English autumn days grew shorter. Partridge would privately lobby individual band members to convince them of his plan to quit touring. This plan wouldn’t come to fruition but by December, the band had recorded some thirty tracks. During the album playback, once the group had settled on a fifteen track version of the album, they could not quite believe what they had created.

A one chord drone, the first sound you hear on English Settlement, is broken suddenly by stadium sized drums. ‘Runaways’ is a Colin Moulding sketch that would be elevated by an arrangement utilising the band’s new toy, the Prophet-5 synthesizer. Having come on the market only a couple of years previously – over in Hollywood, Michael Jackson was using the same piece of kit for the paranoid, sleek pop of Thriller – its use was the first indication that XTC were overcoming what Partridge referred to as his “moral chastity belt” of only using sounds that could be reproduced live. Like a British road movie – think Radio On – the action begins with a young girl taking the highway to the neon city, unable to tolerate the screams of her violent home any longer. What this girl might find is unpacked across English Settlement’s dark panorama of British society in the 1980s.

As the album was being written and recorded, that other English settlement – the post-war one – was disintegrating in real time. 1981 was first phase Thatcherism, the hit-and-miss years where the visible human costs of high unemployment still led many (not least within her own party) to suspect the whole thing would be a cruel and short-lived experiment. "The whole Swindon area seemed to be under the hammer” reflected Colin Moulding in a 2009 interview, “Mrs Thatcher had come to power a couple of years before and everything was being battered to the ground.” For Moulding, the recent demolition of Swindon’s Baptist Tabernacle – a large, 19th century meeting place described by Sir John Betjeman as the town’s St Paul’s Cathedral – seemed symbolic of these shocks, and prompted him to write the terrace chant of ‘Ball And Chain’. Almost sarcastically, they grafted the opening chimes of the Beatles’ ‘Getting Better’ to the intro.

In the British music press, XTC were frequently derided as backwater casualties – something Partridge, with his leering West Country burr, resents profoundly to this day. What the London music press missed was that Swindon was perhaps the ideal suburban vantage point through which to catalogue the changes happening to Britain in the early 1980s. On Partridge’s ‘Leisure’, his lyric bears witness to joblessness, observing a new Swindon leisure class drowning in alcohol and video games. “What a waste of breath it is” shouts Partridge deliriously, “searching for the jobs that don’t exist”, before collapsing into a terrific, discordant alto sax solo.

The topography of Swindon provides further inspiration on Moulding’s standout ‘English Roundabout’ – a jittery reboot of Pentangle’s ‘Light Flight’ inspired by Swindon’s so-called Magic Roundabout. Consisting of five linked mini roundabouts, the 1972 construction is regularly cited as one of England’s most frightening junctions.

Nothing at all in ‘Senses Working Overtime’s two-chord, medieval peasant opening verse would suggest a top 10 hit. It would be the only proper hit single Andy Partridge would ever write and sing. Psychic collapse and mental overload stuffed into a nursery rhyme, its sugar rush chorus was crafted by reversing Manfred Mann’s pop-arty “5-4-3-2-1.” Though penned by the least druggy band imaginable, its lyrics clearly suggest the psychedelic experience. Across British indie music in the 1980s, the influence of the Byrds would be pronounced but largely confined to a jangle through some arpeggiated chords. Here, Dave Gregory takes Roger McGuinn’s John Coltrane influenced frenzy on Eight Miles High as a fevered starting point, spraying 12-string Jackson Pollock colour across the stereo. Like many of XTC’s best ideas, it’s used extensively on one album and then ditched forever.

Dipping into his pockets for English ephemera, Partridge recites the strapline of a popular brand of matches: “England’s glory, a striking beauty.” Though there are no solely acoustic or folkish tracks on the album, it’s frequently referred to by critics as pastoral. This is a red herring – if it’s pastoral, it’s only in the way that nettles or thorns are pastoral. Its sentiments are bubonic rather than bucolic.

Time and again on English Settlement, XTC use the studio to match the disorientation and cosmic weariness of Partridge’s lyrics at that time, and never more so than on ‘Jason And The Argonauts’. A journeying song written by a man driven to near madness by travel, Partridge frames his disgust and disappointment in increasingly mythical and grandiose terms. “I have seen acts of every shade of terrible crime from man-like creatures” spits Partridge. He would later describe the track as being about “un-niaving” and “unravelling” and even the straight-up pop of ‘Senses Working Overtime’ contains nightmare prophecies of buses skidding on black ice and birds falling from the sky. This is XTC at their most prog, the track is bookended by a few bars of crystal bright cymbal crashes against Partridge’s chopping guitar line, painstakingly produced to evoke the glint of sunlight on a wide open sea. The idea of the sea was important. During the phased, strange bridge, Partridge pants and wails beneath guitar lines and weird echoes that threaten to drown him. Sonically, as on the sinister, dubby waltz of ‘Yacht Dance’, it aspires to be as bewildering as psychosis.

Though much of English Settlement is reporting from the frontline of Partridge’s England, it’s social comment without ever being social realism. An upbringing on cheap sci-fi and comic books leads Partridge to open a song about a neo-Nazi with words like “the insect-headed worker-wife will hang her waspies on the life”. ‘No Thugs In Our House’ is all rockabilly slap-echo, Chambers’ hooligan drumming and Partridge’s hellfire scream employed to tell the story of Graham who is sleeping, whilst his parents, the police, and the Asians who have been badly beaten by him try to make sense of his action. It’s acidly written, the parents straight out of Alan Bennett (“no thugs in our house, are there dear?”) mistaking his National Front badge for a boy’s club logo. Not unfairly, XTC’s reputation is as Little Englanders, but English Settlement is far less celebratory about its country than might have been remembered. It’s a sour, paranoid England of racist violence, the arms trade, demolition, domestic abuse, unemployment and war.

Post punk’s mandatory doominess was never theirs, but on English Settlement, Partridge had arrived at similar conclusions of his own volition. ‘All Of A Sudden (It’s Too Late)’ is an ink black treatise on the futility of life, on what to do when you have realised that the happiest moment of your life has already passed. “Life’s like a jigsaw” mourns Partridge in the track, “you get the straight bits / but there’s something missing in the middle.” In its wintry arpeggiated abstraction, it anticipates Bends-era Radiohead. Seemingly an enigma even to its songwriter – who recalls very little about its composition or recording – it’s one of the standout moments in the XTC catalogue.

The third side of English Settlement is its strangest and most experimental – all four tracks trading in a weird internationalist funk. The wiry, taut groove of ‘Melt The Guns’ is an indignant missive against the military industrial complex – Partridge even rapping about judgement day in America and racial sterilisation. The hypnotic ‘It’s Nearly Africa’ suggests the influence of Talking Heads’ Remain In Light, released a year prior to the English Settlement sessions. Paired with ‘Knuckle Down’s camp plea for racial unity (“knuckle down and love that race!”) it’s a faintly naive but ultimately sweet political statement. XTC’s small-town earnestness might have seemed backwards of the discourse in 1982, but forty years later its clarity of message and universalism endures beyond the demands of post punk’s political specificity.

The only tracks that underwhelm on the record – ‘Fly On The Wall’ and the freak-ska of ‘Down In The Cockpit’ – are still perfectly passable, and indeed, the b-sides released from these sessions suggest better material held back due to internal politics. Certainly, nobody talks about what a good single album English Settlement might have made. The final track, ‘Snowman’, is the album’s finest exponent of what critic Jazz Monroe refers to as Partridge’s fondness for “melodic trapdoor, establishing awkward patterns and flooding your serotonin receptors at unexpected moments.” More than this, it fixes a key XTC lyrical trope – Partridge as the holy fool, the jester who tells the truth, the Mayor of Simpleton. “If you made a dunce cap, I’d don it” is as close to romance as Partridge ever achieves.

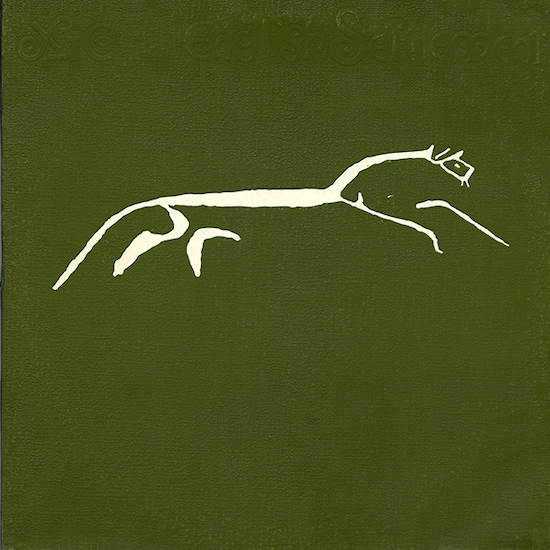

Driving out from Swindon and Wiltshire into Oxfordshire, turning right on the Magic Roundabout, you will pass one of the earliest great works of English art – the Uffington White Horse. Its genesis is contested but consensus settles on it being a Bronze Age statement of worship to the horse god Rhiannon. The band all grew up in the shadow of the Uffington White Horse and understood its power as a symbol. “It’s literally a kind of Iron Age advertisement for an English settlement that was on the top of the hill” explained Partridge in an interview US magazine Progressive Media in 1982, “and it’s us living here, settling here.” Partridge described the title as “ambiguous”, reflecting its record’s deep ambiguity about English life in the 1980s. The use of the Uffington White Horse would mark the beginning of XTC’s fascination with the old weird England – stuffing later albums with songs about harvest festivals, maypoles, the myth of the Green Man, sacrificial bonfires and ritual child murder.

On release, English Settlement was greeted critically with either begrudging respect or dismissal. In a 5 star review, Sounds’ Hugh Fielding correctly identified “a wealth of potent pop that comes dangerously close to art”, concluding that “after living with the tape for a couple of weeks, I feel that I’m only just getting to grips with what this album has to offer, which you can take as a recommendation or a warning, depending on your state of inverted snobbery.” Over at the NME, however, Paul Morley declared himself “monstrously undazzled” by an album he declared “not particularly brave, intimidating, exacting, puritanical or impressive.” It’s easy to mock the grandeur of Morley’s review, but it’s revealing about why XTC were so frequently overlooked. These were years of bold pop innovation, of future shocks and grand spectacles. Andy, Colin, Dave and Terry could never compete.

With distance, however, XTC’s direction of travel rhymes closely with that of Kate Bush and Talk Talk. Just what was it about England in the 1980s that led these three singular artists to retreat into the studio, walking backwards towards competing visions of the English pastoral? Three weeks after English Settlement, the Fall released Hex Enduction Hour, similarly a desperate roll of the dice by a frontman determined to wrestle control over a group at the expense of any kind of conventional success. There was, for XTC, some conventional success. English Settlement charted at number 5, though it would behave like an indie album and drop from the charts altogether after just one week. Partridge began to worry that in making an album so complex as to obviate the need for touring, he had in fact only created more demand.

XTC would be booked into an intense schedule of British, European and American dates that should have swallowed 1982. Partridge awaited the tour like a convict awaits sentencing. A week into the tour, the band had been scheduled to perform a live televised show at Paris’ Le Palace theatre. All that Partridge could see on stage was an audience now spinning at 78rpm. All that the audience could see was a singer fluffing the chorus to the opening song, turning at an angle to face the drum riser, before gently removing his guitar and exiting stage left. Partridge was having a profound panic attack. The concerned band found their singer collapsed in the foetal position backstage, he had not eaten in days. No more grim proof could be needed that Partridge was too unwell to tour. And yet. Two weeks later, a nearly broken Partridge was on a plane to the US. He struggled through the first show in San Diego. The following night, before a sold-out Hollywood Palladium, he found himself unable to leave his bed, thinking he might finally be dying. “It took me an hour to walk the hundred yards from the hotel up the road to meet the band” Partridge told Q magazine in 1989, ”I really thought I was cracking up.” XTC never performed live again.

The scale of debts against cancelled shows that Partridge had made clear he was in no position to complete reached over £250,000. It swallowed his life savings, and the funds had to be borrowed against future royalties from Virgin. Convalescence for Partridge was slow, he spent weeks too afraid to leave the house. A course of hypnotherapy only hardened Partridge’s resolve that he had no future in touring, only in Swindon. During this time, he wrote ‘Love On A Farmboy’s Wages’, a genuinely pastoral song that joined the dots between his grandfather’s rural poverty and his own economic agreement with Virgin. Drummer Terry Chambers walked out on the band for good during its rehearsals, it would form the centrepiece of Mummer, an album that failed to make the UK top 50.

Because of chart positions like this, the conventional wisdom is that XTC exist as a kind of cautionary tale. All that brilliance, so little recognition – not least in the country they so clearly adored. Partridge waged war on the music industry, and the numbers show a man that lost and kept on losing. Except, he didn’t.

Andy Partridge never once set foot in a cramped backstage room again, never had to travel, and instead spent the next two decades with XTC making exactly the kind of unfashionable, exploratory records that he wanted to. XTC retreated to the studio, left alone to nurture their eccentricities – military history, toy collecting, a tendency to wear period dress in photoshoots. It could be ugly – they squandered a serious purple patch by going on strike action against Virgin Records in the 1990s, an arrangement which suited Virgin Records more than it did XTC. All the same, Partridge achieved exactly what he set out to achieve when he began plotting English Settlement. The band recorded a further nine albums, two of them doubles. 1986’s Skylarking, produced in conflict with Todd Rundgren, became a minor US college radio success. In 1993 Nonsuch was nominated for Best Alternative Album at the Grammys. 1999’s ambitious Apple Venus Volume 1 might just be better than them both.

If it was a struggle for XTC to do this then, streaming and artists’ consequent reliance on live revenue would have rendered this impossible now – not least for a group of working class, council house musicians – but it’s an extremely valid path for artists to take. Would any of Brian Eno’s great leap forwards in the 1970s had been possible if he was lugging a touring group around Europe? Do you seriously believe SAULT would have just delivered five flawless records in the last three years had they been doing the festival circuit? We ask a lot of our artists, and it’s to be mourned that the option that artists such as the Beatles, Kate Bush, XTC, Talk Talk and Brian Eno took no longer exists.

“Thirteen years of Valium addiction had been kicked, and I was thinking clearer and deeper about life,” reflected Partridge in a 2007 interview, “I didn’t want to be the packhorse on someone else’s money-making treadmill. I wanted to be a backroom boy record maker. No fame, just fine art.” Andy Partridge won.