What did the Left of 80s pop want? To persuade, or to overthrow?

For Redskins, the soulpunk firebrands whose only album Neither Washington Nor Moscow… has just received a long-overdue reissue as a 4CD box and heavyweight vinyl LP, the answer was clear and direct, and we’ll come to that. The rest, however, comprised a coalition of blurred agendas and muddy thinking.

Before I start naming names, I need to bookend it by saying that I love most of these bands, and most of these records. But there was a beseeching, petitioning quality to much Leftist pop. The Special AKA, on ‘Free Nelson Mandela’, were "begging you please". The Beat similarly begged Margaret Thatcher to ‘Stand Down Margaret’, politely adding the word ‘please’. Their spin-off group Fine Young Cannibals, on tracks like ‘Blue’, addressed the problem of social deprivation and directly blamed the Government, but spelled out no solutions. Simply Red, covering the Valentine Brothers on ‘Money’s Too Tight To Mention’, did the same. UB40 could sing on ‘One In Ten’ about the starving babies who are a "statistical reminder of a world that doesn’t care", but asking the listener to care, rather than bring about radical change, was the boundary of their remit. The Christians, covering The Isley Brothers, asked "When will there be a harvest for the world?" All questions, no answers.

The Style Council, at least, had insurrectionary intent. ‘The Whole Point Of No Return’, on Cafe Bleu, was a meditative thought experiment about overthrowing kings and queens, lords and ladies: "Rising up and taking back the property of every man… Just one blow to scratch the itch…" And their single ‘Walls Come Tumbling Down’ was an overt clarion call. When push came to shove, however, they put their energies into Red Wedge, a movement designed to herd young people in the direction of the ballot box rather than rising up or pushing down any walls.

Morrissey daydreamed of regicide and political execution – "Her Very Lowness with her head in a sling", ‘Margaret On The Guillotine’ – but his alienation and misanthropy prevented him from putting his shoulder to the wheel of a mass movement: The Smiths did join the Red Wedge tour, but for only one gig.

Pete Wylie of Wah! filled his songs with inspirational buzzwords like ‘hope’, ‘pride’, ‘self-respect’, ‘faith’ and ‘dignity’ which had become the lingua franca of Soul-cialism, peppered throughout the works of The Faith Brothers, Working Week and The Kane Gang. (Although he did also sneak "Hats off to Hatton!", a reference to Liverpool’s controversial Militant council leader, into the fade out of ‘Come Back’, and used the R-word – revolution – on the long version of ‘Story Of The Blues’.)

The Housemartins, with their motto ‘Take Jesus – Take Marx – Take Hope’, at least hinted towards revolutionary leanings. Their Go! Discs labelmate Billy Bragg also seemed to be on the right side, but his working class hymn ‘Between The Wars’, so arresting when he performed it on Top Of The Pops, ended by lamenting the loss of ‘sweet moderation’.

Like I say, I love most of those bands, and most of those records. They spoke to me, they inspired me, they had my back. But the default setting of the 80s pop left was to make an impassioned plea to the floating voter, the centrist, and appeal – naively, in hindsight – to the better angels of their natures.

One band said "Fuck the floating voter." During the Miners’ Strike, when centrists wrung their hands about picket-line violence against police officers (while remaining curiously quiet about violence in the other direction), only one band – at least, only one band who were anywhere near the radar, or radio, of the average teenager (sorry Test Dept, but face facts) – were advocating workers taking "the reins in our hands" and changing their reality through direct action. That band was Redskins.

In the summer and autumn of 1984, with the Miners’ Strike at its height, it genuinely felt to this 16 year old as if revolution was in the air. Especially in South Wales, where I’m from. My home town is not a mining town, but the docks town the coal came through on its way from the Valleys to the world. I come from one of those Welsh families where, when you dig back through the genealogy, you hit a point where everyone’s either a preacher or a coal miner. (One of my ancestors had his legs broken when Churchill sent in the troops into the Valleys to crush the miners.) The struggle 10 or 20 miles to the north was not remote or theoretical to me, but real and vivid. It was, literally, close to home. I remember chucking dinner money into an NUM collection bucket shaken in the school corridors at lunchtime. The Conservatives had declared class war, enacting the Ridley Plan (the 1977 internal Tory report on union-crushing tactics whose first tenet was that "the government should if possible choose the field of battle"), but it truly felt as though the working class was equal to the challenge and that the miners could win, and bring down the Thatcher government. Stakes were high. Everything was up for grabs.

One thing we knew, though, was that we couldn’t rely on the Labour Party to get behind the strike. Historically it seldom has, and its leader Neil Kinnock – a son of a miner, from the pit community of Tredegar – shamefully threw the miners under the bus by refusing to fully side with Arthur Scargill and the NUM, hiding behind the lack of a national ballot as his excuse. Kinnock’s treachery was actually worse than anyone realised at the time: in 2009, in the book Marching To The Fault Line: The 1984 Miners’ Strike And The Death Of Industrial Britain by Francis Beckett and David Hencke, it emerged that Kinnock had secretly contacted the National Coal Board in an attempt to preserve coal supplies to the steelworks in Llanwern, directly betraying the striking miners’ efforts. This is the man the Red Wedge bands wanted us to rally behind.

Into this heightened, polarised, febrile atmosphere came a single which understood all this. Redskins’ ‘Keep On Keepin’ On’ came out in October 1984, heralded by a blast of Stax horns, a thumping Tamla backbeat and a bracing "HAH!" Its lyrics were a million miles from the imploring begging-you-pleases of other left-leaning pop. It laid out the situation ("they whip us into line with the threat of the dole"), and delivered unequivocal support to the strike as a means of overthrowing the status quo ("the bosses are going down", "if it takes a year, we’ve got to take a year…") It was an unimaginably thrilling disc – significant credit must go to its somewhat unlikely producer, Nick Lowe – and brought Redskins to the brink of national fame, stopping just short of the Top 40 but reaching No.10 on John Peel’s Festive 50.

Originally a punk band from York called No Swastikas, Redskins were the trio of singer-guitarist Chris Dean, bassist Martin Hewes and drummer Nick King (later replaced by Paul Hookham of The Woodentops). Dean, as Redskin-sceptics forever delighted in pointing out, had spent two years at a public school in Reading (actually on a scholarship, but that detail was often omitted). His father, a British army gunner, died of a brain tumour when Dean was seven. Martin Hewes, too, lost his father young, to an industrial-related illness from his job at British Leyland. Both youths had been steeped in politics. Hewes’ hippy mother brought him into contact with radical ideas, and he read Orwell’s Homage To Catalonia at 13. He spent his teens attending radical festivals, including a Rock Against Racism event in Leicester where he got caught up in a pitched battle with police. Dean joined the Socialist Workers Party at 16. Hewes was also a member. It was in this militant milieu that their music was forged.

As SWP members, Redskins were Trots rather than Tankies (as their album title makes abundantly clear, being a contraction of the SWP slogan Neither Washington Nor Moscow But International Socialism). Their debut single ‘Lev Bronstein’ was a tribute to Leon Trotsky, and their label was named CNT in honour of the Spanish anarcho-syndicalist party who refused, during the Civil War, to fall in line with Soviet instructions. For them, revolution was an ongoing process enacted by the workers and transcending national borders rather than a one-off, top-down, vanguard-led coup in one country. Tapping NME readers on the shoulder and asking them if they wouldn’t mind voting for Neil Kinnock is not what Redskins were about.

This "Marxist-Leninist rock’n’roll band" (their description) were first noticed in their nascent No Swastikas form at a RAR benefit in Leeds by Jon Langford of fellow travellers The Mekons ("left-wing skinheads – brilliant!", he remembers thinking), but it wasn’t until they decamped to London and rebranded themselves Redskins that they began to make waves.

Choosing to present themselves as skinheads was not without controversy, The skinhead movement, though originally born of the white British working class’ love of black Jamaican music and style, had long been tarnished in the public imagination by association with football violence and the Far Right. Redskins, however, were from the part of that movement which refused to cede ground to the knuckledraggers and remained true to its anti-racist roots. In this respect they were kindred souls with a broad umbrella of overlapping organisations such as SHARP (Skin Heads Against Racial Prejudice) and Anti-Fascist Action, and bands such as Angelic Upstarts before them and Blaggers ITA after them. They even inspired a Red Skin subculture across Europe which persisted long after the band had ceased to exist.

The three Redskins put their own twist on the skinhead look. Lean, wiry and serious of brow, Chris Dean wore a red Harrington like his namesake James Dean, and boxer boots not bovver boots, made for agility not aggro. The image was tough, utilitarian, practical, ready for the fight. (As we’ll see, they needed to be.)

Their first live appearance as Redskins was on a flatbed truck at a Fares Fair march for affordable travel, organised by the Woolwich Right To Work Campaign, in front of about 60 people, on the same bill as anarcho-punks Conflict. (Dean made it clear that he had no time for anarchists, making a point of slagging off Crass.)

However, the gig which has gone down in history as their official debut was in a community hall near London Bridge, at the end of a SWP-organised Jobs Not YOPs march on the same bill as comedians/poets Attila The Stockbroker, Alexei Sayle and Seething Wells (aka journalist Steven Wells, sometime housemate of Martin Hewes). The show was witnessed by Garry Bushell for Sounds, who praised them for "bashing out fiery salvoes of uncompromising protest with such gusto that any latent heckler was sent packing for the boozer rather than risk their wrath" while complaining that they didn’t sound like an Oi! band and telling them to cut their hair even shorter.

On record, Redskins didn’t hit the ground running. Debut single ‘Lev Bronstein’ sounded like a scratchy Joy Division demo and sank without trace. However, follow-up ‘Lean On Me’, which repurposed a Bill Withers songtitle, a Supremes/Vandellas backbeat and a Dexys-esque horn section for a vow of class solidarity, took them to No.3 in the Indie Chart. Flipside ‘Unionize!’, too, delved into black musical traditions with its super-fast calypso-funk scrabblings as it urged praxis over preaching: "We can talk of riots and petrol bombs and revolution all day long. but if we fail to organise we’ll waste our lives on protest songs…"

Repurposing and appropriating black American music as a vehicle for polemic was, of course, a common trick in the 80s. Critics were not unanimously impressed. Reviewing a Redskins show at Central London Polytechnic in January 1986, Melody Maker‘s Simon Reynolds wrote, "I find vaguely repellent the idea of Redskins unlocking the secrets of this magical music, harnessing its redemptive and transfiguring power, only to use it as vehicle for protest. So ulterior." After accusing them of stating the obvious and preaching to the converted, he added "Redskins are the Clash of the new soul and what we really need is its Sex Pistols. A group that can work from soul’s unrealism, its dangerous ecstasy, to make unreasonable demands." A recording of that show survives. Before their song ‘Plateful Of Hateful’ (which features the brilliant/awful pun "Every picture sells a Tory"), Dean launches into a rant about the royals, dedicating the song to "all those bastards like the Duke Of Edinburgh, Prince Charles, Lady Diana, Sarah Ferguson, Prince Andrew, all those bastards that are unemployed all their lives… and get more dole than me or you ever can, or ever will." Within a few bars, the song incorporates snatches of Isaac Hayes’ ‘Theme From Shaft’. You can almost hear Reynolds’ hackles rising and his Biro scratching the notepad.

Bad reviews were all part of the game, of course, as Chris Dean knew only too well. He had begun writing for NME under the pseudonym X Moore after he sent a review of his own band, No Swastikas and they were sufficiently impressed to ask him to be their Yorkshire stringer. He was savvy and quick-thinking enough to engage with his critics, even in the middle of a show. At a gig in Glasgow, Melody Maker‘s Lynden Barber saw him enter into a dialogue with a heckler from the balcony, a striking miner, who took issue with the singer’s hostility to the Labour Party. "The hordes at the front the stage leap to the wrong conclusion, yelling ‘Scab! Scab!’ in unison," Barber wrote. "’He’s not a scab,’ corrected Dean, but nobody seems to know what’s really going on…"

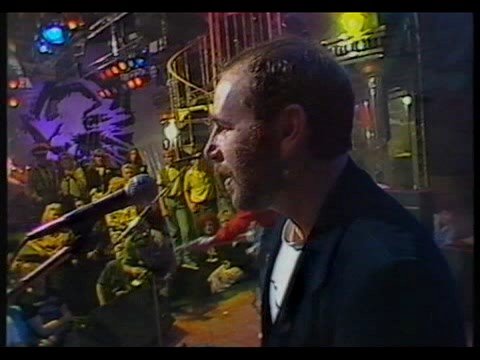

The third Redskins single, ‘Keep On Keepin’ On’, got them a slot on Channel 4’s The Tube at the height of the Miners’ Strike. Midway through that song, the band brought on a Durham miner with the improbably perfect name of Norman Strike to deliver a speech. Mysteriously, his mic was cut. Show producer Malcolm Gerrie later denied any skulduggery. When Melody Maker‘s Lynden Barber questioned him about bands using The Tube to proselytise, Gerrie replied "Like the Redskins?! Ha ha ha! Bless their cotton socks. Well. The official line is The Tube is not a political platform, it is at the end of the day an entertainment programme with a small ‘e’ — that is our brief to Channel 4. So if a band wants to use The Tube as a political platform then really they’d be better off doing it elsewhere, because we’re not geared up for it. However, because of the freedom of the programme and the fact that it’s live, people have taken the opportunity of getting in there. The miner on with the Redskins, that was bad luck because he decided to pick a mic that hadn’t been working from the start of the Redskins’ set." Sabotage or not, Strike’s words weren’t heard by any of the viewers. He would later re-record them for the Redskins tribute album Reds Strike The Blues. What we should have heard included the statistics that "There have been six miners killed, five on life support machines, three miners with fractured skulls, and over 2,500 serious injuries", and the parting shot "Miners’ support groups have sprung up all over the country. They’re supporting us. You should be supporting them."

The rough-edged punk-and-soul of ‘Keep On Keepin’ On’, more than anything they released before or since, perfectly embodied Redskins’ aspirations. Their mission statement, famously, was to "walk like The Clash and sing like The Supremes". Chris Dean’s feelings on The Clash, however, were mixed. "They were the most exciting and dynamic band I have ever watched at a gig," he once said, "even though it was obvious to me as a 15-year-old that their politics were flabby and stank."

Even Billy Bragg wasn’t left wing enough for Redskins. When Melody Maker held a Red Wedge debate, Dean found himself on the opposing side of the table, rubbing shoulders with Tories while attacking Bragg for selling out. This is the Billy Bragg who had made his support for strikes perfectly clear by covering Leon Rosselson’s ‘A World Turned Upside Down’ (about The Diggers) and Florence Reece’s ‘Which Side Are You On’ (about a 1930s coal strike in Kentucky). That said, Redskins did record a live cover of Bragg’s ‘Levi Stubbs’ Tears’ for a miners’ benefit EP put together by Wake Up fanzine. But even on that occasion, Dean couldn’t resist a quick jab at Billy before the first verse: "This is a song by Neil Kinnock’s publicity officer…" (Bragg, graciously, nevertheless said it was his favourite cover version of one of his songs.)

Redskins stood as an uncompromising moral conscience against which all other left-wing pop could be checked, their mere presence keeping them all honest. Where other bands’ vague wishy-washy utterances amounted to "we should all be nicer to each other", Redskins had the specifics of their agenda absolutely nailed down. They knew their stuff. If there was a band you’d back to have an opinion on Zinoviev, it was Redskins. And they walked it like they talked it, stepping out first thing in the morning to sell copies of Socialist Worker and standing on picket lines for hours on end. As Chris Dean told Adam Sweeting in Melody Maker, "If Weller or Strummer sing about picket lines, picket lines are always things that happen in their songs, never something that they themselves go down to."

Redskins put their lives on the line for their beliefs. On 10 June 1984, a group of bike chain-wielding white power skinheads led by notorious British Movement organiser Nicky Crane attacked the band and their fans during a show at the free, GLC-sponsored Jobs For A Change festival in Jubilee Gardens on the South Bank. From then on, Martin Hewes would keep a baseball bat stashed behind his amp. As bad as the South Bank incident was, things could easily have been a lot worse: at one Redskins gig in Germany, Hewes later revealed, three guns were confiscated at the door.

The band had little time for the performative charitable activities of their peers. In a speech at Marxism ’85, Dean referred to Band Aid as "Egos For Ethiopia", and he was consistent in his critique of Live Aid, a concert which raised enormous sums to save lives in the short term but did nothing to radically restructure the global economic system which allowed – indeed, required – the existence of inequality, poverty and starvation. (In this, The Housemartins were in agreement: "Too many Florence Nightingales, not enough Robin Hoods", Paul Heaton sang on ‘Flag Day’, a song with the chorus "It’s a waste of time, if you know what they mean/ Try shaking a box in front of the Queen.") Dean called Live Aid "sickening" in Smash Hits, and caused a minor furore to erupt by daring to question the sainted Bob’s methods: "I wouldn’t particularly criticise Bob Geldof, the bloke thinks he’s genuinely doing something, but basically it’s charity, and charity never solved anything, and never will do. All these people who are giving donations – yeah, it does help to relieve the starvation, but in five years time, that starvation is going to be back again."

One sense in which Redskins did compromise was in regard to that vital Marxist question: their relation to the means of production. Rather than keeping it independent, they – like The Clash before them and Public Enemy after them – signed with a major label, Decca/London. This tied in with Dean’s belief that it’s more important to "get your hands dirty" and reach people rather than hide behind cult status. The relationship, however, proved problematic. When the band wanted their next single, ‘Kick Over The Statues’ to be a fund-raiser for the Anti-Apartheid movement, Decca refused. Redskins took matters into their own hands and put it out on Abstract Dance, an imprint previously associated only with Britfunk band The Cool Notes (although its parent label, Abstract, had put out fellow travellers The Mekons). All royalties went to FESATU (the Federation of South African Trade Unionists) and the ANC, and on the accompanying tour, the band took Bruce George, a black South African activist along to tell the audiences about the country from first hand experience. With a video which drew attention to London monuments related to Britain’s historic ties with the Apartheid regime, it chimes uncannily with the modern era of statue-toppling street protest: "At the end of an era, the first things to go/Are the heads of our leaders kicked down in the road…"

Another sticking point with Decca was the band’s preference for playing benefit gigs rather than getting into the studio. For Dean, it was a no-brainer to prioritise "the most important struggle that any of us here have seen in our lifetimes." One can understand why performing to audiences felt like a more direct and effective means of communication. At their peak, they played to 200,000 people at an SOS Racisme gig in Paris in front of the scene of an actual revolution, the Bastille.

By the time their one and only album came out, however, the Miners’ Strike had been lost, giving the whole enterprise a somewhat mournful, valedictory air, and rendering certain songs, not least the once-electrifying single ‘Keep On Keepin’ On’, feeling as redundant as any former miner.

In hindsight, though, it’s an extraordinarily exciting artefact which stands up as a defiant document of resistance. It positively crackles with catalytic energy. The Constructivist artwork sets the tone, with its Battleship Potemkin still and its scattering of apposite quotes. "Ours is a history littered with the human debris of moderate men," runs one unattributed example. "Once they have disarmed us, they never fail to crush us." (Another from the young Danny Baker, to the effect that "There’s no point having a revolution unless we shoot the bastards afterwards", has not aged so well.)

Superb opening track ‘The Power Is Yours’ builds from a slow bass-and-fingerclicks opening to full-on soul testifying, like an agit-prop ‘Try A Little Tenderness’ but with incitements to "Look to Petrograd, look to Barcelona" instead of romantic advice. Which is exactly the kind of Trojan Horse hijacking of soul that Redskins’ detractors despised, of course.

For me, their shortcomings are… longcomings. Chris Dean, by his own admission, sang from the throat not the gut (often leaving his voice shredded by the third date of a tour). But it’s perfectly suited to the urgency of the message. Similarly, the rhythm section aren’t The Funk Brothers or The MGs, but there’s something pleasing about the unembellished, spartan (Spartacist?) dryness of Hewes and Hookham’s bass and drums as they push things relentlessly forward. And the brass section – Kevin Robinson, Trevor Edwards, Ray Carless – are everything, on tracks like the majestic ‘Bring It Down (This Insane Thing)’ and ‘It Can Be Done’ (eventually released as the band’s final single in May 1986).

The spell is broken a couple of times. At the start of Side 2, ‘Hold On’ is a slice of frenetic rockabilly which doesn’t quite work, and midway through the side, the ponderous ‘Take No Heroes’ feels strangely doom-laden and defeated. Far better are the Northern Soul stomper ‘Turnin’ Loose (These Furious Flames)’ and the bustling white funk of ‘Let’s Make It Work’, which isn’t a million miles from The Higsons or Gang Of Four.

For years, it has felt as though Redskins and Neither Washington Nor Moscow slipped through the cracks of history somehow, erased from the official version of the Eighties. (When I wanted a Redskins T-shirt, I had to make my own.) The deluxe reissue addresses that. Its four discs go far beyond the album and essentially gather together everything the band ever recorded. To pick out just one fascinating rarity, the band’s abortive third Peel Session, unfinished and unbroadcast, featured a track called ‘The Most Obvious Sensible Thing’, a musical adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s 1931 poem ‘Der Kommunismus Ist Das Mittlere’ (‘Communism Is The Middle Ground’). There’s also a 68-page booklet from Hewes and Hookham, with contributions from Paul Morley and good old Redskins-bashed Billy Bragg. The red and black vinyl versions, though inevitably slimmer on content, make up for it in sexiness. If your Materialism is of the non-Dialectic kind, they’re both wonderful things to own.

At the time of its original release, however, Chris Dean seemed disconsolate. "We’ve had a bit of a crisis after the Miners’ Strike as we saw audiences dropping," he said in an interview. "Thousands during the strike, and now 500-600. There were some rock’n’ roll problems with the label and promotion and so on. But a large part of it was the end of the strike. During the strike for a year I never thought, ‘what are we doing’. It was obvious, now that is different."

Stripped of what he saw as Redskins’ raison d’etre, it all felt futile. "A lot of people have had grand ideas of punk. People had a romantic idea that music could change the world and all sorts of farcical and ridiculous ideas, like music on its own is so powerful, but it is not. It is incredibly bloody weak. It is only when it is linked to political struggle like during the Miners’ Strike that it really starts to mean anything."

"At the moment," he added, "because working class people aren’t really fighting, the Redskins is very much abstract propaganda. It’s like firing shots in the dark."

In the light of such comments, it’s not surprising that the band wound down their activities, playing one short tour of Europe and splitting up shortly afterwards. One version of the story is that Tony Cliff, de facto leader of the SWP and Chris Dean’s mentor, told him that his energies would be better spent selling newspapers directly to workers rather than singing songs. Another has it that Martin Hewes walked out. In a 2019 interview with OpenEye Film (whose ten-minute Redskins documentary A Flame That Can’t Be Dimmed is also on YouTube), Hewes suggested that a clash of personalities was at play. "He (Chris) underestimated the contribution that the rest of us made. And the biggest underestimation he made of our contribution was our patience with him. He sorely underestimated how bloody patient we were with him. And the fact that we didn’t turn around and kick the fuck out of him. Because he was at times so utterly obnoxious." (Hewes also remembers Dean telling him he wanted to write love songs, despite having publicly stated that he’d never been in love.)

What happened next is somewhat shrouded in mystery. Paul Hookham played on a Shelleyan Orphan album and briefly joined folk group The Barely Works. Martin Hewes had a stint with soul band Raj And The Magitones and briefly played with The Jesus And Mary Chain. He now works as a music educator.

Chris Dean, however, has withdrawn from sight. He is said to have dabbled in immediately post-Redskins projects called P-Mod and Chris Dean & The Crystallites, but after that, the trail goes cold. Some reports have him living at some stage in Milan, others in Paris, or Berlin. The most credible intel is that he now lives back in York. The question "What happened to Chris Dean?" is frequently asked online, and the word ‘recluse’ gets trotted out a lot. But if he doesn’t want to be found, that must be respected.

Neither Washington Nor Moscow found us, and that’s what matters.

Neither Washington Nor Moscow is out now on London records