Elvis, dapper Darrens, Ibiza Sharons and "men out of control on gear fear" are just some of the characters that appear in ‘Treetop’, the new collaborative track between The Bug and Sleaford Mods’ Jason Williamson, as Williamson leaps from vivid lyric to vivid lyric, much like a chimp swinging from branch to branch in a jungle treetop. Squelching yet menacing electronics hiss against gargling bass-heavy beats provided by Kevin Martin, as The Bug, in a potent collaboration between the two.

Not for the first time in his lyrics, you’ll hear a poison dart "fuck off" delivery in ‘Treetop’ from Williamson, as everything from overpriced bacon sandwiches to 60-a-day smokers rolls off his tongue with his unmistakable and idiosyncratic delivery. However, the partnership with Martin pushes things into new terrain, with the charge, intensity and unpredictability of Martin’s beats matching Williamson’s lyrical twists and turns.

‘Treetop’ is one part of a double single release out on Ninja Tune, which is accompanied by ‘Stoat’. The latter comes to life with sharp, tense, seesawing strings as Williamson begins to list animals that he is not: polecat, stoat, rat, ferret. What follows is probably one of his most direct rap tracks, as Martin’s industrial-tinged beats kick into life and the track unfurls, sitting somewhere between grime and Martin’s usual mix of bass bouncing nods to dub and dancehall that buzz and pulse away underneath.

Williamson is in particularly funny and cutting form on ‘Stoat’: "Fuck your rabbit / 12-bore farmer, bring your drama / I’ll fuck them all, I’m dogging 16 car parks in an hour," before his farmland, animal and car park sex explorations soon move, dream-like, into completely new territory and he’s targeting ‘cosy journalists with no life experience / five stars for a wank record on no-one’s lips."

Williamson has been a collaborator and guest vocalist with many other acts, including The Prodigy, Leftfield, International Teachers Of Pop, Scorn and Snowy, while Martin has been a prolific and varied collaborator for decades, with his work as The Bug often as defined by guest MCs and vocalists as his own distinct musical concoctions. Outside of The Bug, there’s also projects such as Techno Animal (now ZONAL) with Godflesh’s Justin K. Broadrick, and King Midas Sound with Roger Robinson and Kiki Hitomi.

The resulting two tracks have managed to elevate themselves beyond feeling like a guest vocal simply slapped on top of some leftover material as the pair make a riotous but seamless partnership. Below, they talk exclusively about this new collaboration, what connects them, pleasing and displeasing their wives, Britain, and what might be next.

How did you guys come together?

Kevin Martin: The first time we started communicating was on Twitter because I picked up on Jason’s love of raw, independent hip hop and we started communicating.

Jason Williamson: We had a common interest in artists like Westside Gun.

KM: We talked pretty soon after about the idea of working together, but then Jason worked with Scorn, Mick Harris’s thing, and I thought out of respect to Mick, because we move in similar circles, I’d lay off the idea. Then we didn’t really talk about it for a couple of years until around the time of working on Fire and I reached out again. There were some rhythms that I wanted to use on the album that none of the other MCs had picked up on. I just sent one of those to Jason to see if he liked them.

JW: When he threw that over it was like, ‘Fucking hell, Jesus Christ, I’ve got to get something on here with this geezer’. I;m excited for people to hear it; I haven’t played it to anyone apart from my wife, Claire.

Thumbs up from your wife then?

JW: Yeah, it got the seal of approval from Claire. She manages the band as well, but she knows what I’m doing, she knows what I’m best at, she just picks up on it straight away. She can be quite horrible [with feedback] sometimes.

KM: For my wife, my shit is never heavy enough. She was listening to Merzbow at 17, so when I put some filthy kick distortion all over the place I can see her eyes smile. I just know I’m under pressure to make shit heavy enough for my wife to like it.

JW: These tracks are fucking heavy man. It’s an absolute leap into some kind of trembling void – whatever you manage to conjure up with those fingers of yours.

You guys both seemed to be very productive during the pandemic. Do you feel your independent DIY approach meant you were quite well suited to that situation or did it impact negatively on your creativity?

KM: I don’t think anyone’s suited to that environment. You just adapt. I’m a dropout, really. My father kicked me out of home at 16 and I dropped out of college at 17. I wasn’t born with silver spoon connections so my whole musical life has existed out of desperation, terror, hunger and addiction to music. Music has always been what stimulated me more than anything as a way of trying to understand this fucked up world we all live in, and it’s become even more fucked with the pandemic.

I think if my tools were sharp to deal with it, that’s perhaps why. There’s no time for self-pity or writer’s block. I have to feed my family, and sitting in a corner of a room crying ain’t gonna help shit. It made me all the more intense about my craft and that’s how I dealt with the pandemic. Since music is all I’ve got, it’s my only way of contributing or finding any form of balance.

JW: I just got on with it; it was a case of having to. It didn’t really bother me, creatively speaking, but it was fucking odd. It was dogshit really.

What did you expect to come out of this pairing up?

JW: I didn’t know what to expect because a lot of collaborations are never as close to you as your own work and that’s no disrespect to anybody but your own work comes first all the time. But I really, really like these – I’m very happy with them.

KM: Working with Jason, it almost sounds trite to say, but it’s an obvious fit. The core of Sleaford Mods is very similar to the energy I feel I’ve been working with since I first started making music. It’s the same need. I’m sure Jason is the same as me in that I didn’t make music as a career move, I made it because I had no choice. It was therapy to try and make sense of a fucked world and I get the feeling that’s exactly why Jason and Andrew make their music too.

JW: Oh, God yeah. I mean initially for me I just wanted to be famous, but that soon disappeared.

KM: I think mine was to empty every room I played in.

You both grew up in places – Grantham and Weymouth – that weren’t typical music towns or considered cultural hubs. Being into American hip hop, how much of that was like a peek into another world? And how key was it in shaping your identities?

JW: I think for mine and Kevin’s generation, Public Enemy were our Elvis Presley. That early Def Jam output really, really caught my attention for a couple of years and then I floated out of hip hop until around early 2004 when I randomly discovered Wu-Tang Clan, and that’s when I started properly taking note of the techniques, methods, ideologies and philosophies about it.

KM: As a very young kid at school, I remember seeing kids doing the rowing dance to The Sugarhill Gang. Then I heard ‘The Message’ by Grandmaster Flash and I didn’t know what it was, same as when I heard Public Enemy the first time. I knew I was magnetised to it; it was the same language of ‘fuck you’ that I wanted and needed.

Then the Bomb Squad inspired me hugely as producers. Then, like Jay, I drifted in and out of hip hop, but It’s always stayed there, it’s been a constant in my life. There’s something about the primal energy of a simple loop and a raw lyric that was at the core of hip hop that continues to speak to me now.

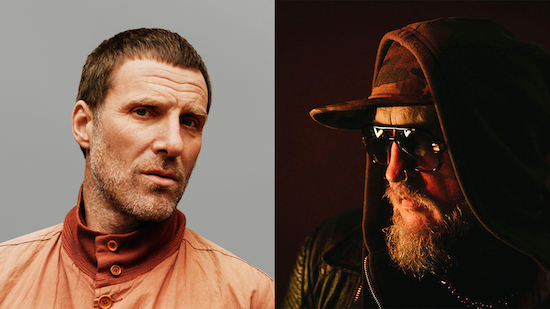

‘Treetop’ art by Zake Clough

You’re both very unique artists on an individual level but you also lean heavily towards collaboration. What makes for a successful collaboration?

KM: That I want to do more with that person. Also I like the fact that collaborations have got a bit of a dirty reputation because a lot of them are just done for money. A good collaboration is taking two different chemicals, putting them together and getting this third magical chemical you didn’t expect.

JW: Back in the day, collaborations were always for the love of it and now, as you’ve just rightly said, Kevin, they are for crossing into other audiences, streaming figures, blah, blah, blah. Which is fine, I understand people have to earn a living, but what happened to just tipping up at a studio and laying down something? That’s what collaborations like this remind me of.

Jason, do you approach your lyrics in the same way you would for a Sleaford Mods song or do you separate material?

JW: The approach to lyrics is no different than Sleaford Mods. Kevin gave me the beat and I worked on fresh lyrics straightaway. I wanted to try and experiment more, and on ‘Stoat’ especially, there’s a kind of different flow. The lyrics are all kind of gibberish; a lot of sentences that mean something then back into surrealism.

Kevin, any lyrics that stood out for you when you heard them?

KM: What I’m fondest of is that I’m still trying to make sense of them. I think that’s the beauty of what Jay does. There’s absolutely an in your face realism but that’s totally balanced by mysterious surrealism – you have the two extremes covered.

Jason, you’ve mentioned the lyrics are a way to get out anger and frustration. Was there anything doing your head in at the time of writing these?

JW: I think I had some really, really stupid hang up about looking at touring bands’ support acts and thinking they only put those acts on because I put them on my playlist. Which is absolutely insane. I would get laughed out of court for that. But I love toying with the idea of paranoia, the ego and what stupid things you sometimes pin to the sides of your ego. I use it as a vehicle for that kind of expression.

There’s also lots of other stuff in around memories. The idea of stoats, the animal, is around my stepfather who used to be a poacher so you’ve got that old culture coming in a little bit. You’d always have dead pheasants hanging up in the back of the house and he’d train you to gut them and cook and eat them. A lot of that imagery was coming back to me as well.

KM: I like how tangential they are. Even the titles ‘Treetop’ and ‘Stoat’ are interesting because I’ve got this sort of perennial urban albatross that follows me everywhere and I just like the fact that the titles are really not people would expect.

They are a bit Wind In The Willows, aren’t they?

JW: Kevin understood that things could be a bit surreal and a bit scratch your head, ‘What the fuck is he on about?’ That’s what I loved about it.

Do people overlook or misunderstand some of the more surreal moments in your lyrics, Jason? I guess a typical view of someone who doesn’t like Sleaford Mods may be, ‘Oh, it’s just some bloke ranting’. Is the surrealism lost on people sometimes?

JW: I think so and it kind of pisses me off. Also, a lot of people accuse you of being bitter and say things like, ‘I’ve never met anyone as bitter as you’, and it’s like, ‘Well, what’s wrong with that?’ I mean, I can understand it if you walk around being bitter all day, it’s gonna get in the way of things, but for a creative I think it’s a beautiful tool. It’s a lovely colour to put on your palate.

KM: There’s that temptation for people to view anger as a cartoon emotion but for me, it’s a reflection of fire and passion. There’s this thing, musically, philosophically, lyrically, that people want to assume that anything that’s complex has more value than something that’s just simple and to the point.

There is this caricature of how people deal with intensity in lyricism and often it’s just brushed aside as being a bit base and a bit stupid and a bit cartoon, and it’s just not the case. For me, with Sleaford Mods, I thought there was a mad complexity going on in terms of contrast and contradiction. The same applied to people who inspired me to begin with like Mark E. Smith with The Fall, who was always a genius at magic realism with in your face fuck off. I need both.

An exploration of Britishness is often the foundation for a lot of your lyrics, Jason. Kevin, you left the country years ago to live in Berlin and now Brussels. How are you feeling about British identity given where we are currently at?

JW: I think Kevin had the right idea and fucked off. I’d love to. It’s a miserable place at the minute. I don’t know how I feel about British identity. I think the only way I can communicate it is to just simply be. I’m not looking for anything with it because it’s such a damaged animal at the minute, it’s completely lame. So British identity is what you see before you, I guess, whatever that is. I certainly think part of British identity is racism, and years and years of misguided education being fed to the lower classes. That’s a massive part of this country, which it needs to get rid of.

KM: I felt alienated from birth. Any sense of Britishness was just totally in turmoil growing up in a seaside town where you’re a target for sailors, Air Force and Army because all three bases were around that town. They would beat the shit out of me.

Nationalism in any form is a turn off, it’s bullshit. I feel a free spirit and I want to remain so, psychologically and geographically. I moved to London because I couldn’t deal with the South Coast and that completely whiter than white mentality, and casual and blatant racism. That feeling that the country was defined by hatefulness against others. I’ve no English blood in me anyway; my mum and dad were Irish and Scottish. I feel rootless and I see it as a positive.

This collaboration was born from a Twitter exchange a few years ago. Is it still a place where ideas can be exchanged and new relationships form, or has it become overly hostile?

JW: It’s really hostile but I hang around purely because of networking, socialising with people like Kevin, and other musicians I occasionally talk to that I wouldn’t do via text message or email. I like that relationship. Sometimes you can exchange ideas but most of the time it’s fucking horrible.

I experience a pile on about once every three months. It can be quite stressful but I stick in there purely because it’s an amazing tool to reach out to other creatives. That is our life now, isn’t it? Being online. It is our reality now. The outside world has taken second precedent to that. I use the outside world to eat and go to the toilet, the rest of the time I just exist online.

Can we expect any more from this collaboration?

JW: If there’s time I’m definitely up for it, if Kevin is.

KM: Same. What’s been fantastic is that it feels like a beginning point. I’m already thinking, ‘Shit, I wish I tried to send something like this or that to Jay that had a different edge, texture, tone or intensity’. It feels like there’s a lot of space to explore how we accommodate each other’s aesthetic.

What I like about this is it’s got that what the fuck factor, like, what the fuck is this? But these tracks are really hooky to me too. I’ve gone from when I started making music and doing everything I could to piss people off to now actually enjoying the perversity of adding sick hooks.