In the past, people saw omens everywhere. The world was full of unknown perils, and other threats that were thought to be known but were just as arbitrary and dangerous – miasmas, imbalances of the humours, god’s wrath. To an understandably superstitious population, portents were a way of trying to divine the order beneath reality.

It’s not as backward a proposition as it might seem – science aims, via evidence and inquiry, at a similar understanding, albeit with more rigorous methodologies. If everything in the universe is deterministic, as a priest or a physicist might suggest, then perhaps there is a way of uncovering the plan. We might then learn the future, in search of profit or simply comfort. Scholars spent entire lifetimes becoming lost in gnostic labyrinths trying to explain the mysterious mechanics of existence but there was a short cut – auguries. The word means specifically ‘the divination of the future by examining the flight of birds’, but has become a term used for all methods of reading omens. Augers were, to the diviners, glitches in the code of the everyday, revealing what lies beneath.

We’ve come a long way since then. We have moved beyond superstition and look with pity if not scorn at those poor bastards long ago, trying to work out the ways of the universe by staring at markings in the dust or investigating trajectories of geese. We now know the names and shapes of the microbes that destroy us. We can now deduce what shitstorms the future has in store. Our anxieties are of a more sophisticated nature.

In truth, of course, we are more like our ancestors than we’d like to imagine. Knowing more certainly brings advantages but it hardly brings comfort. We are still the same anxious creatures in a perilous world, though we have learned to read the signs better. And the auguries are still there. Entire industries, from the markets to meteorology, are based on deciphering and then predicting what will happen. Even the old auguries contained grains of truth – birds, for instance, fly away from incoming storms and natural disasters. There is another archaic word for this – prodrome. It comes from the Ancient Greek for ‘running ahead’ and it reaches us via its medical use: signs or symptoms of an illness before it has fully manifested.

For the first part of their career, Radiohead’s work was full of auguries. While Pablo Honey largely deserves its dismissal as angsty juvenilia, the band learned something valuable in their reaction to and rejection of it – not to simply vent but to understand and represent that which you are at odds with. The Bends and OK Computer are filled with ominous references to technology, the security services, capitalism, future shock etc but also physical and mental collapse.

The strands repeatedly converge – the near-deaths via airbags, embolisms and plane crashes, industries designed to alleviate dysfunctions and neuroses that other industries have created, but there’s still an authorial distance. We are falling ill and it’s the very modern world that has extended our lives and our illusions that is doing it. Things can only get darker, to misquote New Labour’s chosen anthem of the time. The Bends and OK Computer were not just auguries but prodromes. Kid A, by contrast, is the onset (I’m doubtless not the first to diagnose this), and by the time of Amnesiac, we are immersed in a shadow-world of the unwell.

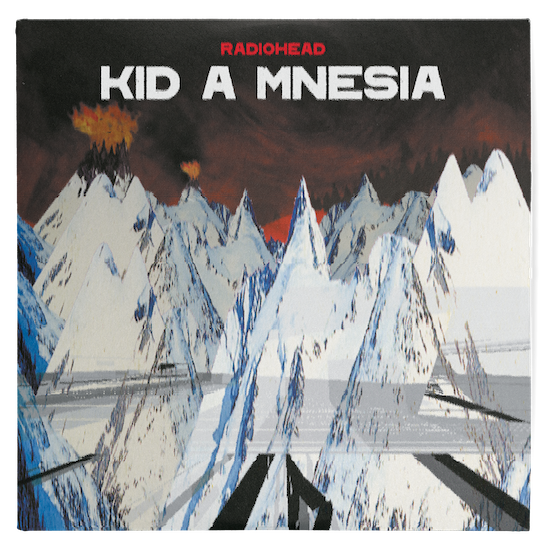

Often, KID A MNESIA – a joint reissue of the band’s fourth and fifth albums with previously unreleased material – sounds like the soundtrack to dreams and nightmares, sometimes simultaneously. "We’ve got heads on sticks / And you’ve got ventriloquists / Standing in the shadows at the end of my bed," goes Kid A‘s title track. Stanley Donwood’s corresponding artwork is like something a scarred child would draw in recollection, which is made even more disconcerting by the wicked gallows’ humour throughout. "Everything in its right place," Yorke sings on the opening track, and, you know, everything is not well at all.

Reassessing the album, over twenty years later, it now seems like everything went right. Kid A is regarded as not only a classic but a paradigm-shifting album in terms of popular experimentalism. Many see the album as their peak, but the acclaim was not as universal at time. It’s worth remembering the sense of disdain even revulsion, given critical consensus doesn’t do this unorthodox album any favours. The feeling, by some, that the band had leapt off the edge though was mistaken.

There was a limit to what they could do following the Pixies/Jeff Buckley path and a repetition of themselves resulting in The Bends II would have led to diminishing returns. They had brushed up against the mainstream with ‘Creep’ and come away chastened. They were right to veer leftfield. The decision is often put down to what they were listening to. The influence of Warp Records visionaries like Squarepusher, Aphex Twin and Autechre is evident throughout, as is the free jazz of Ornette Coleman and Charlie Mingus, the kosmische Musik of Can and Neu! and earlier experimental artists such as Arthur Kreiger and Paul Lansky (both sampled on ‘Idioteque’).

Choruses and verses were replaced by a focus on layering over hypnotic grooves, disruption, dissembling and rebuilding, the creation of space, contrast and colouring, and the power of leaving things out. It loosened the band up to allow gaps, conjure atmosphere, subvert themselves essentially by resisting their inclinations, and occasionally freaking out. Though they could have gone in any direction, this path was suggested from the start of their career; the band are named after a Talking Heads song, and the collage approach of Remain In Light and Byrne and Eno’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts is crucial. Yet influences can be overstated. Much of the abrupt change of Kid A comes down to Thom Yorke switching from guitar to piano. The band switching their focus to rhythm. Jonny Greenwood deep-diving into obscure musical history (hello, ghostly ondes martinot). And above all, the paramount importance of learning to dance.

For an album that is so concerned with inertia and disassociation, it seems like an escape to freedom now. Donwood’s desolate cataclysmic cover of Kid A seems an odd place to want to escape to, as tempting as the land east of Eden must have looked. Its glitching graphics seemed anachronistic even at the time, adding to the feeling of it being an unplace like the limbo, cloud cuckoo land etc. that follow. It seems to embody the feeling of breakdown and depersonalisation that Yorke notes that he felt throughout the album’s inception, having dreams of being pursued down the Liffey by a tidal wave or feeling like he was falling through the earth while speaking to people. These psychological disturbances which haunt the music may also be an attempt by the mind to deal with being in an overwhelmingly alien experience. Indeed, it might be as much a tool to use against disorder as it is a disorder itself – hence Michael Stipe wisely advising Yorke that he should say to himself in the midst of the intense pressure they were facing, "I’m not here, this isn’t happening" (the centrepiece of ‘How To Disappear Completely’). Yorke’s notes from the time confirm this astral projection strategy, with references to clicking heels like Dorothy in The Wizard Of Oz to return home.

Expected to make a grand statement and unveil a colossus after The Bends and OK Computer, Radiohead responded with a work of disintegration. Stipe features significantly here too, as a mentor to Yorke but also because his lyrics show the enigmatic power of collage (hence the cut-ups that begin with ‘Everything In Its Right Place’). This approach places KID A MNESIA in an unlikely modernist lineage wherein coherent naturalistic narrative is the lie rather than the experimental, given how disconnected and endlessly changing our lives and thoughts are. There is a psychological component to this, namely that attempting to believe that the abnormal is normal is unsustainable, only recognising it as such will offer a foothold to begin from.

In another work written in the midst, aftermath and recovery from a breakdown, T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, the poet writes, "These fragments I have shored against my ruins." There is method in the madness, in all the splintered texts and hallucinatory doodles scattered throughout KID A MNESIA and its visual art collected here. It is a means of survival, shoring up the fragments to surviving the tidal wave of fame, which for all its financial benefits is profoundly dysfunctional. Kid A was not something they dared to do but something they had to.

So, aside from how strangely warm and soothing the opening notes of Kid A sound when once they sounded so icy and disturbing, what surprises are to be found in the reissue? The curious quality of the unreleased tracks are how much they belong to the world, and band, before Kid A. The languid ‘If You Say The Word’ is kept buoyant by a subtle almost-reggae rhythm. It’s experimental but conventional in sound structure, akin to ‘Climbing Up The Walls’ (whose moments of claustrophobia sit among the beauty it shares). The acoustic ‘Follow Me Around’ might not have sounded out of place on Pablo Honey. Both are fine tracks, and worth returning to, but their absence on the finished albums is a testament to the band’s notorious discernment (spending years trying to satisfyingly capture songs – ‘True Love Waits’, ‘Nude’ and so on). Their inclusion would’ve felt like hedging bets or a dilution. It’s fitting that both are accompanied by videos that, despite the use of modern cameras and drones, feel stuck in that time (there’s an echo of Chris Morris’ contemporaneous series Jam to both). Escape is, again, a prevailing theme. ‘Follow Me Around’ embodies the Pied Piper figure that Yorke’s lyrics and notes of the time obsess over and yearn to flee, while ‘If You Say The Word’ does point to the future, foretelling In Rainbows in its lyrics and having a hint of the seductive quality of that album.

The alternate versions of ‘Fog’ and ‘Morning Bell’ are intriguing (the former has a surprising kind of swing to it) and they are pretty, but they don’t surpass or subvert the versions of both that are already out in the world. ‘Alt Fast Track’ races to nowhere in particular. The string arrangements and variations on existing instrumentals are interesting in the way that exploring an artist’s studio might be or examining the swirls and blobs on their palette but there are no unique hidden masterpieces we haven’t already heard to be found. The exception to the rule, in terms of Radiohead’s discernment, is the ‘Why Us?’ take of ‘Like Spinning Plates’ which is a revelation and, arguably, instrumentally superior to the original. The outtake is closer to the live piano-led version on I Might Be Wrong; less distorted (though it still has a David Lynch sound design feel to it), it absolutely soars. There is a nebulous feeling though overall with the unreleased material; these are the clouds that planets and stars will later form from but they are ethereal in themselves.

One of the achievements of KID A MNESIA is to give equal footing to the overlooked sibling that is Amnesiac, an album that is, to my mind at least, a more rewarding treasure trove than the sparse but nevertheless sublime Kid A. There is something of the attic to Amnesiac. It’s a lost book in a derelict library in a far distant post-literature time. Joining the two albums, you realise how remarkably productive this troubled period of writing and recording was for the band. There are so many astonishing moments but crucially, perhaps through their studies of electronic, classical, jazz and kosmische Musik, they are allowed space to breathe to build. The band learned not just the power of rhythm (evidenced in ‘The National Anthem’, ‘Idioteque’, ‘Packt Like Sardines In A Crushd Tin Box’ and elsewhere) but the power of restraint and release. The highlights are like those peaks on the cover of Kid A – the swoon halfway into ‘You And Whose Army’, the orchestral dissonance and then soar in ‘How To Disappear Completely’, the early-hours in New Orleans slump of ‘Life In A Glasshouse’, every single mysterious second of ‘Pyramid Song’ – but the other tracks have enabled their greatness by being quiet melodious valleys or moors filled with apparitions.

We may not be able to hear these tracks again with the shock and intrigue we did upon their release, partly because the pluralised virtualised world of music we inhabit, where you can listen to any genre, is partly down to Radiohead’s blurring of boundaries between genres, which were much more rigidly policed then than now. For all the claims that Kid A, in particular, was alienating and obscurantist, the legacy is one of opening up possibilities for musicians and listeners. And yet these are two weird numinous albums that still defy canonisation, despite the plaudits. Instead of the monolithic monument Radiohead were poised to deliver, as the tradition of guitar bands insisted upon, they created one album that is like moving through a fog-shrouded landscape with strange shapes looming into view, and the second a haunted room filled with arcane texts and drawers filled with cryptic messages and cursed objects. KID A MNESIA does not rest easily in the mind and, in making it, Radiohead demonstrate the importance of refusing to rest easy.