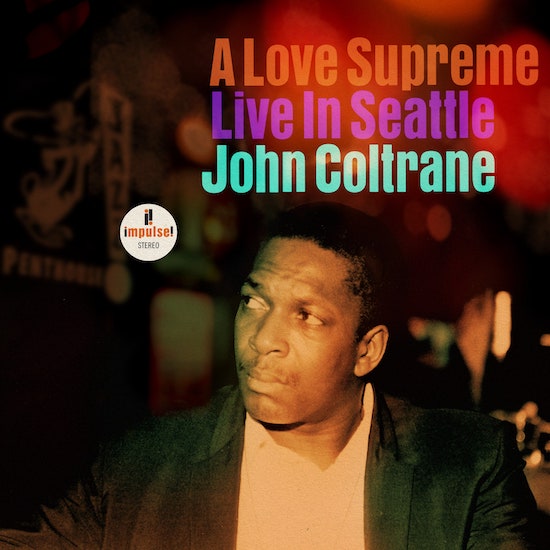

To suggest that a newly discovered live recording of John Coltrane’s A Love Supreme is a significant event for jazz scholars and Coltrane devotees is something of an understatement. Since its release in 1965, the work has accrued both mythic status and mystic heft. The pristine, 33-minute suite is divided into four parts – the modal invocation of ‘Acknowledgement’, the heavily swinging hard bop pieces ‘Resolution’ and ‘Pursuance’, and the concluding hymnal ‘Psalm’ – which, together, form one of the most perfectly realised and beautifully self-contained statements in 20th century western art.

Coltrane himself evidently considered it to be a special work, too. Conceived and executed at the end of 1964 as an offering to the Almighty, it marked the beginning of the overtly spiritual path that the saxophonist was to follow for the few short years remaining to him until his passing in 1967. Moreover, this heartfelt statement of sincere devotion seemed to sit apart from the rest of Coltrane’s oeuvre. While pieces such as ‘Naima’ and ‘My Favourite Things’ were endlessly revisited and reworked in performance up until his death, A Love Supreme was, for a long time, believed to have never been included in his live repertoire.

That changed in 2002 with a deluxe reissue, which included a performance of the entire suite recorded at the Festival Mondial du Jazz Antibes in Juan-les-Pins, France on July 26, 1965. Though half as long again as the studio take, with extended solo sections stretching it to 48 minutes, this live iteration feels surprisingly faithful to the energy of the original. Yet, at the same time, it’s also possible to detect Coltrane bringing new vibrations to his performance, incorporating harsh, braying barrages that show him straining at the limits of expression, pushing himself to find ways of revealing his evolving inner state. This sense of ongoing transformation is even more urgently apparent in another, newly unearthed live version now being released for the first time.

Recorded in Seattle on October 2, 1965 – a few months after the French performance and 10 months after the definitive studio session was laid down – this new find reveals a version of A Love Supreme mutating so furiously, expanding its possibilities so profoundly that it seems in danger of devouring itself, of imploding under the weight of its own momentum. In fact, it’s possible to view the differences between the three extant versions of the suite as a metric of the ferocious velocity of John Coltrane’s artistic and spiritual development at the time – one that highlights how his essential energy was always devoted to a process of becoming, of transit between different states, and specifically between form and formlessness. Ultimately, it gives the lie to the black and white notion that Coltrane had a swinging, earlier period and an avant-garde later period. He was always busy becoming something new.

To appreciate this fully, it’s worth positioning the Seattle performance in the context of Coltrane’s timeline for the year 1965 – a time of almost superhuman growth, during which he teetered on the raw cusp of change, constantly flickering back and forth between a familiar hard bop aesthetic and a free jazz future. It was a condition that produced some of the most thrilling music of his entire career.

The year had begun with the release of A Love Supreme in January but, by the summer, it was already clear that Coltrane was reaching beyond the hard bop and modal styles it contained. He recorded the aptly named Transition in May and June and, in August, cut Sun Ship (released posthumously in 1970 and 1971 respectively), both with the same Classic Quartet who’d recorded A Love Supreme and with whom he’d worked exclusively since 1962 – pianist McCoy Tyner, bassist Jimmy Garrison and drummer Elvin Jones. Both Transition and Sun Ship contained hard-driving, blues-based numbers powered by Elvin Jones’s relentless power-swing, but they also stretched into less constricted regions, with Jones using mallets, toms and cymbals to sketch textural washes over which Coltrane was free to wander. Between these two dates, on June 28, Coltrane recorded the monumental Ascension, an epochal statement widely considered to be one of the founding documents of high-energy free-jazz, featuring an eleven-piece band comprised of the Classic Quartet augmented by two trumpets, two alto saxophones, two additional tenor saxophones and another bassist.

The possibilities of an expanded line-up continued to preoccupy Coltrane for the rest of the year. On Monday September 27 he began a six-night residency at a jazz club called The Penthouse in Seattle, leading a sextet of Tyner, Garrison and Jones plus Pharoah Sanders on tenor and Donald Rafael Garrett on second bass. On Thursday 30, this configuration was recorded by Seattle-based saxophonist Joe Brazil playing the music later posthumously released in 1971 as Live In Seattle – an album of overpowering intensity with Coltrane unleashing scalding cries and altissimo shrieks over stark, fanfaric bulletins and boiling, endlessly turbulent free jazz undertow. Writing in his ‘Second Letter On Harmony’, the late poet Sean Bonney identified the music contained in Live In Seattle as “one of those examples of recorded music that still sounds absolutely present years after the fact, because it was one of the sonic receptacles of a revolutionary moment that was never realised… a cluster of still unused energies that still retain the chance of exploding into the present.”

The following day, on Friday October 1, the sextet plus Joe Brazil travelled to a studio in the city of Lynnwood, north of Seattle, and recorded the 29-minute free jazz free-for-all OM, released as an album of the same name in early 1968, not long after Coltrane’s death. Some have suggested that the recording session took place under the influence of LSD and, even if, as others claim, this is untrue, Coltrane is generally believed to have begun experimenting with psychedelics around this time. Certainly, OM burns with the spiritual and revolutionary fervour that characterised the latter half of the 1960s, containing crazed horn ululations punctuated by vocal moans of the eponymous Hindu sacred syllable, and bookended by chanted verses from the Bhagavad Gita.

It was against this backdrop of restless experimentation that, the very next evening, on Saturday October 2, the sextet plus young alto saxophonist Carlos Ward took to the stage at The Penthouse for the last night of its residency and recorded a complete take of A Love Supreme. While the four constituent movements remain intact, and the music retains a clear connection to earlier forms, the move away from the compact interactions of the Classic Quartet in favour of the collective energies of an exploded line-up invites a looser, more exploratory reading. At 75 minutes, the suite is more than twice the length of the original and considerably less coherent – yet this sprawling journey is entirely emblematic of the oscillations between form and formlessness that Coltrane was navigating during 1965.

Without comment or introduction, and against a background of quiet audience chatter, Coltrane blows the opening benediction of ‘Acknowledgement’, beginning a dense, 22-minute reading that replaces the devotional vocal chants of the original with multiple percussion, an extended bass solo from Garrett, and Coltrane unfurling a powerful tone with a deep vibrato revealing the influence of Albert Ayler. A bass duet interlude makes way for the hard-swinging ‘Resolution’ with Ward’s alto solo echoing Coltrane’s former collaborator Eric Dolphy with its high, delirious sprays. A pounding six-minute drum solo from Jones signals the entrance of the heavy blues ‘Pursuance’ here tackled at a breakneck speed that encourages a harsh, barking tenor solo from Sanders and a typically furious piano solo from Tyner, with impossibly swift right-hand motifs underpinned by bottomless left-hand depth charge chords. After a long bass solo from Garrison, the final sighing meditation of ‘Psalm’ allows Coltrane to bear his soul, giving full vent to a yearning tone of supplication while the group roll and swell behind him. As the final notes tentatively fade, Garrett asks “Is that the end?” “It better be,” a physically drained Coltrane chuckles, “it better be, baby. Yeah!”

It’s an astonishing document, to be sure, though there are some issues with the recording. The Penthouse’s in-house recording system – which captured this performance – was a simple two-microphone set-up onstage connecting to an Ampex reel-to-reel tape recorder. The two mics were positioned at either side of the stage, around six feet apart. One is clearly close to the horn frontline but, frustratingly, all the horns sound slightly off mic so that the solos are somewhat buried in the melee. Jones’s drums sit firmly centre stage, crashing away indefatigably. The second mic was close to the piano, leaving Tyner sounding somewhat isolated at the other side of the stage. Though accidental, it’s an arrangement that was prophetic of further rapid change to come within the group.

A fortnight later, on October 14, the sextet – with the addition of second drummer Frank Butler and percussionist/vocalist Juno Lewis – entered a studio in Los Angeles and recorded two long tracks, ‘Selflessness’ and ‘Kulu Sé Mama (Juno Sé Mama)’, which were released in January 1967 on Kulu Sé Mama, Coltrane’s last album released during his lifetime. Both tracks reveal that, at this stage, he was still surfing the line between freedom and form: both feature turbulent group improvisation while still being firmly anchored to time by Jones and Tyners’ heavy swinging instincts. The tension couldn’t last, of course, and Meditations – a spiritually intense and mostly rhythmically free excursion recorded on November 23 – was the last album to feature Coltrane’s longstanding drummer and pianist. Feeling increasingly alienated by Coltrane’s avant-garde investigations, Jones and Tyner left the group.

Bookended by two impassioned spiritual missives, 1965 was, then, the year Coltrane’s Classic Quartet unravelled while undertaking a journey between definitive statement and final dissolution. With its end – and particularly the departure of Jones and Tyner – Coltrane finally cut his ties to the vestiges of hard bop, ensuring he would swing no more. His new band featuring Garrison, Sanders plus drummer Rashied Ali and his wife Alice Coltrane on piano, would be the vehicle that enabled him to explore more and more abstract settings, right up until his premature death from cancer, aged 40, in July 1967.

Yet, as the Seattle recording of A Love Supreme clearly testifies, for one glorious year during 1965, Coltrane succeeded in producing timeless music that was utterly experimental while remaining irresistibly rooted in accessible form. Sean Bonney put it best when he suggested: “Next time some jazz fan tells you that late Coltrane is unlistenable, or something, laugh in their ridiculous face.”