This rascal Youngs keeps you guessing, doesn’t he? Being prolific and chameleonic in equal measure, one can only be so surprised at this point, of course. But even so… He’s a fount of ideas, too, and has has an uncanny ability to take a goofy idea (say, symphonic D-Beat, or an album of lovely modern chamber-pop ditties which started as a conceptual art project to collect rejection letters from major labels) and make durable, fascinating work out of it. The intrigue lasts well after the smart-ass snickers die down.

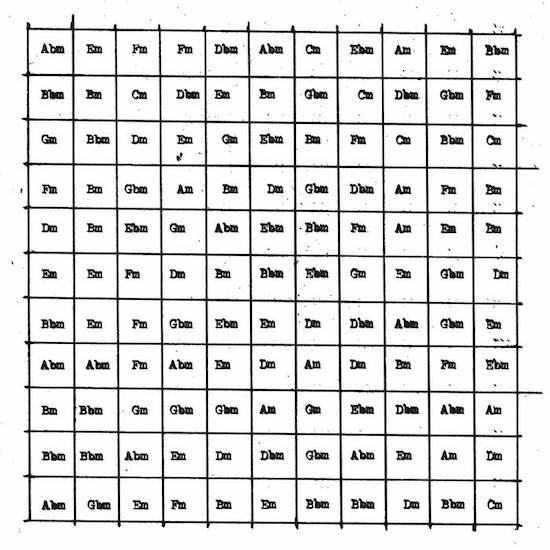

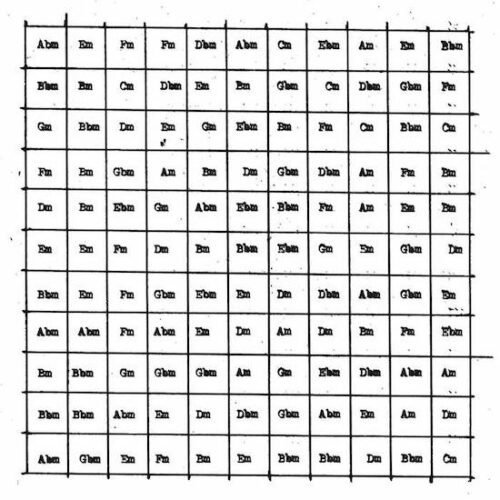

On CXXI, named as such both because the first piece ‘Tokyo Photograph’ has 121 chord changes and because it’s his 121st release, Youngs works to surprise even himself. The aforementioned chords, all minor, are randomly generated and played by sine waves, accented with brushed snare and overlaid with occasional field recordings, electronics, and/or treated trombone provided by Sophie Cooper.

Throughout, Youngs delivers a keening, vulnerable vocal performance akin to classic Robert Wyatt, or maybe Thom Yorke at his most unshakably doleful. This lends ‘Tokyo Photograph’ some vague sense of song, and the sine waves have a pleasing, organ-like tonality that help to make the piece reasonably accessible for a passive listener. Attention, however, reveals a structurally challenging work that, while lovely, is also deeply alien, like grey men successfully imitating the tonalities of western music without any notions about the logic that drives most of it.

The other track on the album, ‘The Unlearning’, continues in this format, but strips the vocals and trombone to lean instead into the electronics – especially tape echo. The subtractions make for a more unmoored work, but despite being almost completely random in its order, the piece’s few strictures imply a direction. The chords refuse repetition, but the rhythm is steady, never allowing the piece to meander.

These two long pieces are a study in chance operations, but unlike a great many benchmark works in that field by John Cage and his ilk, Youngs has set up limitations that make CXXI pleasing to the ear, if not wholly satisfying to the pattern-craving mind. In a sense, this makes the music more transgressive: like Eno or Bryars before him, Youngs has a knack for taking challenging concepts and making them palatable to those who might not otherwise seek out being challenged by music. An invaluable skill, that, and one that’s undoubtedly pried open many a mind over these last few decades.

There’s no telling what Richard Youngs will do next. Walls of broken digital sound? Painfully intimate post-Nick Drake songcraft? Computer-generated abstract polka? It’s best to just wait and see. There’s a real pleasure in being so regularly surprised, even if you expect as much by now.