It may surprise those who assume crime fiction has to follow strict genre rules, but crime writers are as adept at messing with the form as yer average Booker Prize aspirant. This second selection of reviews takes in metafiction, fictionalised versions of historical events, real people saying and doing made-up stuff, books within books, authors appearing in their own fiction, and a book that isn’t a book (yet).

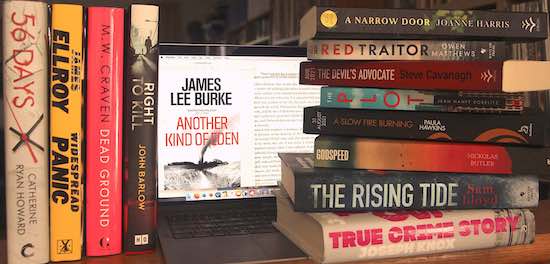

Dead Ground (Constable) is the fourth full-length novel in Carlisle-based author M.W. Craven’s series cataloguing the cases cracked by suffer-no-fools detective Washington Poe and socially maladapted IT maven Tilly Bradshaw. By Craven’s standards, the crime here is uncomplicatedly realist: no serial killer immolating victims in Lake District stone circles or leaving body parts strewn across Cumbrian beauty spots – just a bloke beaten to death in a brothel. Oh, and an opening featuring a falling-out among thieves as they ransack a bank vault, each wearing a mask of a different James Bond actor. The imaginative ways Craven has found to make blood soak into the Cumbrian soil may have attracted attention to this excellent series, but it’s Poe and Tilly that keep you coming back. This is the best of the lot so far, the pair’s personalities now thoroughly bedded in with both writer and regular readers, the characters leaping off the page and assuming an almost corporeal presence.

His methods mean he’s always going to operate best on his own terms, but if future cases cross the border into Yorkshire, Poe could do worse than hook up with Leeds-based detective sergeant Joe Romano. The central character in Right To Kill (HQ), the first of a planned new series by John Barlow, Romano shares many of Poe’s traits – single, bit of an unfortunate and yet-to-be-unravelled back story, largely confounded by the world of smartphones and social media – and is similarly decisive and driven. Yet where Craven rarely turns down the opportunity to raise a chuckle, Barlow’s tonal range tends towards the darker end of the spectrum. He uses the baked-in contrasts his setting affords him quite brilliantly, Romano’s investigation into the murder of a drug dealer whipping the characters between the alleyways and side-streets of metropolitan Leeds and the Spartan terraces scattered across moors and hillsides outside the city. Reading the book while, in the real world, the Batley and Spen by-election rumbled in the background, what felt most striking was the lightness of touch with which Barlow deals with a whole panoply of contemporary issues, and the care he takes to subtly remind the reader that open-mindedness is vital, both to police investigations and for enjoying novels. Just as impressively, the book is pacy without ever becoming breathless, and the spare, economic rendering of both characters and situations allows you to savour the richness of the writing even as you’re swept along swiftly by the plot. It’s an outstandingly good first instalment: the next one can’t come soon enough.

Steve Cavanagh’s New York-based lawyer, Eddie Flynn, is pitched into a situation Romano would recognise all too easily, despite being situated on a different continent. In The Devil’s Advocate (Orion), Flynn and his team are recruited to try to prise an innocent youth from the clutches of a ruthless Alabama district attorney. Randal Korn makes Elmore Leonard’s “Maximum” Bob Gibbs look like a lightweight: he’s sent more men to the electric chair than any other prosecutor in the country. Cavanagh draws on contemporary headlines but works in a world slightly more vivid than our own: his novel lasers in on instances of all-too-real abuses of prosecutorial powers in capital cases, and his antagonists draw succour and support from populist political opportunists who’ve sewn racial division as a means to attain and retain power. He doesn’t quite go full Django, but the denouement is one of which that the master of exaggerated pulp social justice, Quentin Tarantino, would surely approve. You’ll be punching the air come page 395 too.

They’re both set in the Cold War, both draw on historical events, both involve real-life people as well as made-up ones, both rely on (and even sometimes revel in) their characters’ propensities for misrepresentation and misdirection, and both feature members of the Kennedy family in several scenes. But Owen Matthews’ Red Traitor (Bantam) and James Ellroy’s Widespread Panic (William Heinemann) couldn’t be more different. Matthews pulls threads from two infamous incidents during the Cuban missile crisis and expertly weaves them into a propulsive espionage thriller that switches between Moscow and a Soviet submarine dodging American destroyers in the Caribbean. It’s a slick and successful blend of deep research and writerly poise – a thriller that reads like a particularly well-sourced piece of journalism, and all the more enjoyable and admirable for that.

Ellroy has taken time out halfway through his second LA quartet to deliver the first of two planned helpings of noir narrated by the (real) Fred Otash. But this wouldn’t be Ellroy if we didn’t encounter an almost wilful degree of formal and stylistic rule-breaking, not to mention a healthy dose of self-directed iconoclasm. So not only does the book begin in the future, with Otash in purgatory, trying to end his torment by making a full accounting of his earthly transgressions, but Ellroy adopts and adapts the alliterative argot of the Tinseltown tabloids Otash wrote for as his breakneck narrative ricochets around 50s Los Angeles. What astonishes at first is how an apparently breathless style forces you to slow down: there are passages where the prose reads more like poetry. It’s writing to relish, even if the events described are a non-stop cavalcade of debauchery, double-dealing, drugs, drama, deceit, and death. The Demon Dog delivers, indubitably.

Two other writers who appear to be playing in a similar sandpit, though building entirely different castles, are Catherine Ryan Howard and Joanne Harris. In A Narrow Door (Orion), Harris stages a conversational chess match between her two narrators: black queen Rebecca Buckfast and white king Roy Straitley. This third book set in St Oswald’s Grammar (based in part, Harris has said, on her experiences teaching in a boys’ school) is a deliciously drawn-out exercise in storytelling, Harris creating space inside her plot to investigate ideas around gender, class and identity, all while delivering an expertly crafted and atmospherically charged psychological thriller. Howard also toys with the conventions around, and readers’ expectations of, the unreliable-narrator trope in 56 Days (Corvus), a bravura piece of storytelling set in the early part of Dublin’s Covid-19 lockdown. Each chapter is a brief snapshot told from inside the heads of key characters, the timeline splintered, each section acting like a different piece of a stained-glass window – refracting the story in a different way, presenting plot elements in constantly shifting lights. Harris’s novel turns up the heat on a very cold case with action related at a distance of decades, while Howard’s couldn’t be set in a more immediate and timely present – but both books benefit from their authors’ intuitive and relaxed grasp of their likely readership’s moral and social perspectives. These are not just fine pieces of writing: they’re precision-tooled instruments designed for digging inside their readers’ minds.

Ironies abound in the inevitable juxtaposition this column can’t avoid making between the new books by Jean Hanff Korelitz and Paula Hawkins. Both books focus on an author taking someone else’s unpublished work and using it as a sort of sourdough starter for their own, with murderous outcomes the inevitable consequence. Korelitz has enjoyed first-mover advantage, her The Plot (Faber) attracting wide media attention ahead of its release next week, brand recognition high following her 2014 novel, You Should Have Known, being adapted for the HBO/Sky lockdown hit The Undoing. Like Steve Cavanagh, she echoes To Kill a Mockingbird as her slippery, self-justifying literary lightweight Jacob Finch Bonner half-inches a surefire hit scenario from a dead former student, only to find that someone out there in the emailable ether knows the truth. Much fun is had at the expense of the publishing industry and its co-dependents in the media, as Bonner has to turn detective to work out who’s got his number.

In A Slow Fire Burning (Doubleday), Hawkins lights upon similar elements to fuel her storyline, but the games she chooses to play are even more arch and knowing. The book-within-a-book is given an instant, withering review on the second page – an early indication that you’ve signed up for a decidedly different kind of mental workout than that offered by the majority of thrillers. A riff on JK Rowling and Robert Galbraith is ventriloquised by a male author whose surprise hit was published under a female name. Elsewhere, laughing at the absurdities of popular fiction while discussing a dead body on a London barge, the same character jokes that he could mine this topic for the follow-up and call it The Boy on the Boat. Hawkins is doing something very daring and clever here, yet ensures you’re never left feeling she’s being indulgent or enjoying her in-jokes more than you are. Everything works in support of character and plot, all the pieces click satisfyingly into place, and wrapt attention is demanded right to the final paragraph. There’s even a map! It’s enough to make you want to stand and applaud.

Next up, three books that carry their readers off into the wild blue yonder. The bluest and wildest is conjured almost into physical being by Sam Lloyd in The Rising Tide (Bantam Press), with the rare kind of writing that locates the small but very sweet spot between sparse and overwritten and takes up residence for 400 pages. We may be transported to the waters off the coast of Devon in the middle of a once-in-a-generation storm, but Lloyd never leaves us adrift. The plot has more coils than a ropewalk, and the Biblical overtones aren’t reserved solely for the scripture-quoting detective trying to make sense of a case that changes shape and texture with the cloud cover.

Out in Wyoming, the three friends at the heart of Nickolas Butler’s Godspeed (Faber) spend two thirds of the book building a house. But what a house – and what a book. The writing is careful, considered; the story allowed to gradually spool out while tension builds quietly and relentlessly. It’s only after the explosion – sudden, shocking – that you realise every word prior had led inevitably to that moment. Just as impressive is where Butler takes you afterwards: the conclusion may be as bleak and empty as that modernist masterpiece on a remote mountainside that the story focuses on, but Godspeed manages to deliver a credible kind of redemption without compromising the book’s vivid and deeply earned sense of environmental, elemental and emotional realism.

These themes and some of our earlier ones combine right at the end of Another Kind of Eden (Orion), when the narrator, Aaron Holland Broussard, tells us he has “written and published forty books that I have trouble remembering, as though someone else wrote them. The characters in them are strangers and seem to have no origins; the words are like a rush of wind inside a cottonwood tree”. This is James Lee Burke’s forty-first book. He’’s admitted in interviews that he can’t explain how he wrote most of them, sometimes saying he quotes from his own characters in conversation because he feels like those are their words, not ones he gave them. If all this sounds like so much mystical mumbo-jumbo, then perhaps Burke’s books may not gain much shelf space in your soul. But for those readers willing to accept that there are forces at work in the universe that lie towards – and sometimes beyond – the edge of what we can taste and see and feel, there are few writers who can touch him.

Reading Burke causes one to recall John Peel’s gobsmacked encapsulation of the genius of The Fall: “always the same, always different”. Nominally a sequel to 2016’s The Jealous Kind, Another Kind of Eden is, in a sense, the same book Burke has been writing since at least the first of his brilliant Dave Robichaux novels came out in 1987. In limpid, lapidarian prose, power and evil square up to and get faced down by integrity and honesty; the characters and their stories help tell us who we are and who we’ve been, and show how the past impinges on the present to help forge the shape of the future. Like last year’s Robichaux instalment, A Private Cathedral, Burke opens this book with his narrator looking back to a disconcerting episode with decades’ distance, and the story ends not with cold logic and investigatory tradecraft explaining the inexplicable but with a collision between this world and the next, shadows from other dimensions clambering over the walls we’ve built to guard our sanity. In these two books in particular, Burke channels his fellow octogenarian, Bob Dylan: he may be nearer the end of his own story than the beginning, but there is no dialling down of the urgency he feels to say what he has to say, and absolutely no dimming of the power with which he says it. There is, indeed, a distinct sense of an unleashing: as if, before, the writing simply flew, but now, at last, he’s allowing it to soar.Angus Batey

If you’re looking for more ambient terror and for novels that bend the autobiographical style look no further than Joseph Knox’s True Crime Story (Transworld). In a sense, True Crime Story and Bret Easton Ellis’s The Shards (www.breteastonellis.com) are unintended twin books, working with the same basic intuitions and tones, but reaching starkly different results.

Some of the structural oddities of The Shards are glaring. The most evident is surely that Ellis has ditched the normal publication route for now, deciding to narrate a chapter of the book every two weeks as a segment of his podcast. As a result, it flows in a very peculiar manner: it is a syncopated back-and-forth between two Bret Easton Ellises: the author, and the actual narrator of the story. Switching between them, Ellis insinuates suspicion in the listener. He corrects dates, names, locations. I will not claim to know whether any of this is true or false and, as I’m writing this, the novel is still ongoing, but scepticism and a hint of dread at the thought of not really knowing who this Bret Easton Ellis actually is are only natural.

None of these characteristics would qualify as a novelty – neither in contemporary literature nor in Ellis’ personal canon. Serialised novels are a well-established tradition, a fact that Ellis plainly acknowledges in his commentaries, and most of his novels pivot around the faulty perceptions of a damaged narrator. This format and these ambiguities could be dull devices and luckily, once the novel starts rolling, they play a minor role. Deciphering what’s real and what’s fake is a fun puzzle, but these are added bonuses to a story that has far more to offer.

The Shards is never melodramatic, but if I wanted to be disproportionately cruel towards Ellis I’d say that this is his first New Sincerity novel: honest, mean, heartfelt. And this is a stunning description for someone who has always been a jock Alain Robbe-Grillet – whose most famous novels were all surface and no depth, in which a murder is a murder is a murder. The real terror in The Shards does not come from a killer on the loose, but from the certainty of our lovers’ eventual death, childhood’s inevitable end, and the pain of pouring your heart out, sometimes more literally than others. It is ambient terror, lingering everywhere, not dissimilar to the doom that haunts movies like It Follows or the gothic understatement of artists like Bladee or Yung Lean. Listening to The Shards, I kept thinking about a verse by Edna St. Vincent Millay, quoted in Joan Didion’s After Henry: “Childhood is the kingdom where nobody dies”. The Shards is what happens outside the kingdom’s walls.

While Knox’s previous novels were smoky, Joy Division-drenched thrillers, True Crime Story is a faux true-crime story, far more similar to a grimy exploitation movie, hellbent on using any sordid detail it can come up with to manifest unbridled brutality. The dread exuding from each and every e-mail, document and photo fabricated to narrate this missing-girl crime is lingering, omnipresent and somewhat metaphysical. There’s no voice that guides you in the dark and no love to remember when the light goes dim. It is glassy-eyed brutality through and through. Knox’s decision to stick to a spasmodic realism, telling all the story through fragments curated to look like real-life documents that resemble an autobiographical reconstruction of the events not only feels but, even more instinctively, looks right at home with the cold angles of good ol’ exploitation flicks. And like in many of those movies, murder is a sick portmanteau for a truly disgusting world.

True Crime Story is dotted with sentences like: “In publishing, as in the world, we’re drowning in dead girls”. If Ellis’ terror felt like a black cloud lingering over a demonic Los Angeles, forcing the reader to test his mortal limits, Knox’s novel is a fully lit slaughterhouse in which one dead girl is just an irrelevant instance of a well-consolidated trend. Knox’s terror is ambient because it’s everywhere, it’s the core structure of the modern world itself. This, of course, does not mean that True Crime Story lacks any sort of humanity, revelling in a pornographic depiction of violence. There are some genuinely bright spots, moments of true camaraderie in a world riddled with vanished or vanishing girls. The crueller the book gets, the more it voluntarily begs the question of how we can feel any sort of compassion again, amidst horror, sorrow and aching abandon. Most of it is expressed through the tough love Knox uses to describe Manchester itself, the netherworld in which this story takes place – “It was like a man with ‘LOVE’ and ‘HATE’ tattooed on to his knuckles” – but it’s there. The fundamental axiom is clear: narrating crime is the way in which we realise that life is climbing a wall with sharp broken glass on top. Enrico Monacelli