The germ of the idea of these anniversary pieces tends to be the redressing of some wrong or other. Either the article is an attempt to draw some additional attention to a record that was overlooked at the time, or to recontextualise an LP that might have gone on to mean or symbolise something different in the years since it came out. Sometimes they’re an excuse to re-examine a career that feels like it’s ripe for reinterpretation. But on this occasion, none of that seems to apply.

Heaven Up Here was generally considered a pretty great record from the moment it came out, and few have spent much time arguing otherwise since. It made it into Rolling Stone‘s 2012 list of the greatest 500 albums of all time, and narrowly missed the top 50 of a similar poll conducted by NME, whose readers voted it album of the year when it was originally released in 1981. It was the first Echo And The Bunnymen record to make the UK Top 10, back at a time when left-field music didn’t often make significant inroads into the pop chart. It’s by no means your dictionary definition of a lost classic.

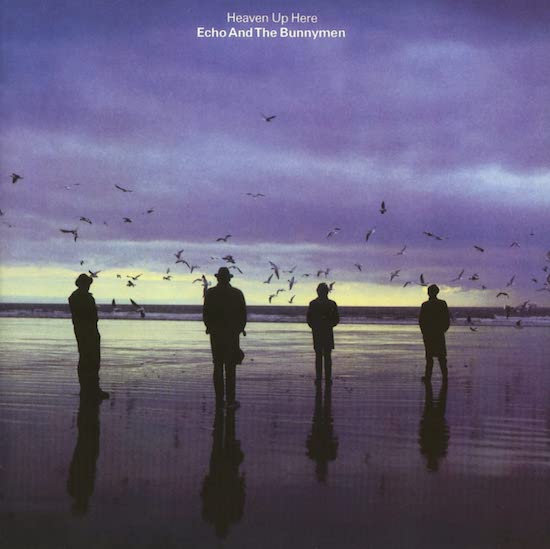

Nevertheless, it’s strange and can feel like it’s holding the listener somewhat at a distance – music defined by the way it strains to hang on to the connections it makes, whereas an acknowledged landmark record usually feels like it effortlessly hits its audience square in the head. For a band who dealt frequently in soaring melody and the most barbed of hooks, it’s an LP chracterised instead by tones and shading: its one single wasn’t a hit, and is largely written using a single chord. Perhaps partly because of its striking, beautiful, painterly front cover – Brian Griffin apparently seeding the Monmouthshire shoreline with bait to entice the seagulls close enough to the silhouetted band – it’s a record that seems to exist in the mind first and foremost as an exercise in mood and atmosphere before one tends to think of it as a collection of songs made up of tunes, rhythms and lyrics.

Somewhat unexpectedly, then, it’s the album from among the band’s great run of four first LPs that most often seems to be hailed as their masterpiece, despite being an outlier in so many ways. It’s singular in its brilliance, rather than achieving greatness by cleaving to or meeting traditional expectations. They may have been one of the great pop outfits of the latter years of the 20th century, but Heaven Up Here succeeds in large part because it doesn’t sound or feel like a pop record. If it’s the defining statement of the band’s career, it is so in large part because it’s entirely unlike everything else they ever recorded. How, and why, did that happen?

Second albums are supposed to be difficult. You spend your whole life writing the debut then have to come up with another collection of songs in under a year – and to do it in your time off between gigs and press and, assuming things are going well, while learning how to be a star and working out how to shake off the burden of expectation that having fans will bring. Yet Heaven Up Here sounds like a record made by a band who aren’t simply finding their groove, but who’ve spent so long inside it that they’ve made it their home. At the same time, if only with the benefit of hindsight, we know that this was a record of a band in transition. So as assured and as certain of its direction as this record is, it was only ever going to be a waystation on the road to somewhere else.

Take that solitary, non-hit single, and let it roll around your head for a while. In some respects, ‘A Promise’ is only half a song: there’s a hook, but not a chorus as such – and the guitar line during it points to a hit that would come later (you can sing the "conquering myself until" part from ‘The Cutter’ over that lead lick and it fits perfectly). Or listen to how Ian McCulloch crafts new songs out of fragments of the past, Del Shannon turning up in ‘Over The Wall’ and Elvis in ‘With A Hip’, just as parts of ‘My Kingdom’ would later be built in Chris Kenner’s land of a thousand dances: if not minting a totally new approach, he was certainly signposting a direction that would be followed by Noel Gallagher and others later on. As certain and as surefooted as it all sounds, this all still feels somehow exploratory or provisional – as if this is a band of great assurance and composure, yet they’re still making their sound up as they go along.

There is, perhaps, something in the idea that, since they’d been a three-piece with a drum machine at the outset, the Bunnymen were still finding their feet as a group on debut album Crocodiles, and that Heaven Up Here therefore marks their "real" debut as a full band. The notion bears only limited scrutiny, Pete de Freitas appearing as co-writer on nine of Crocodiles‘ ten songs: but certainly, he and Les Pattinson were on a different level as a locked-in rhythm section by March of 81, when the band went in to Rockfield to record this second LP. That’s not to say that their contributions before had been undercooked, but the material here was clearly written to what were their growing strengths and the increasing confidence both exhibited as individual musicians and as a team. The band had been on the road pretty constantly, playing unconventional venues in out-of-the-way places, bonding and growing and becoming stronger: by the time they got to the studio they were ready, and by all accounts the sessions were among the best times all involved had during the group’s first flowering.

The rhythm section provided the expansive bedrock, but the credits have to be shared out pretty much equally. For all that, in later interviews, McCulloch has expressed the view that Heaven Up Here was Will Sergeant’s record, among Sergeant’s greatest virtues here are the spaces he leaves within which voice, bass and drums resonate. He deserves as much acclaim for the notes he didn’t play as the ones he did. And then there’s Mac, one of that rarest of new-wave breeds – a singer as opposed to a vocalist – whose contributions both as performer and writer are outstanding. He would sing better and may well have written greater lyrics ("fate up against your will through the thick and thin" is the kind of line that will last centuries) but throughout Heaven Up Here he matches the lyrics’ unsettling dis/un-ease with performances of frequently terrifying power. Go back, again, to that superficially simple single, and marvel at the magic spell he spins: three verses, haiku-like in their precision and brevity, constructed to be superficially similar so as to convey contrasts as wide as oceans – then hear the panic in that vocal performance as the song’s protagonist begs for the certainty that they need, knowing it’s the one thing life can never guarantee. This trick – pitching performances at precisely the right note to turn often vague or sketch-like lyrics into vivid fever-dreams of song – is one he performs several times throughout a record which, once it’s found its way under your skin, can unnerve and unsettle like a ghost story.

If it only works because each of the band was at the top of their game, so too was Hugh Jones. Promoted from engineer to lead producer when manager-producer Bill Drummond and Dave Balfe stood down from duties they’d carried out on Crocodiles and ‘The Puppet’, Jones helped the band craft a record that, played on a halfway decent stereo, stakes a strong claim for legitimacy as a piece of three-dimensional sonic sculpture, never mind its qualities as music. De Freitas – famously discouraged from using hi-hats or hitting anything that would make too sibilant a sound – makes ‘All My Colours’ his own as Jones ensures his battery of tom-toms snap and pop across the middle of the soundstage like an invading army’s tents battered by gale-force winds. In ‘Over The Wall’ the drums clatter across the stereo space in explosive volleys, punctuating squally showers of guitar that jut and joust with bass and vocals. "Let’s get rid of that shit," MacCulloch barks in ‘It Was A Pleasure’, and Jones has his voice placed just ever so slightly off-axis in the mix, and recorded in a way that makes it feel like it’s been beamed in from another country, landing inside the song after a 5000-mile long-wave transmission.

Getting to something this substantial was no accident, yet seems to have been, at least partly, the result less of deliberation than late-blooming inspiration. One of the bits of the Bunnymen saga that’s become ingrained inside the legend is the idea of creative blocks needing to be smashed aside by some kind of forced re-immersion into songwriting. All the band members are on record as citing their John Peel sessions as critical to their progress: Drummond booking one when he knew they needed a kick to re-start the writing mechanism. The best example of this is ‘Taking Advantage’, the early, slowed-down version of what would become breakthrough hit single ‘The Back Of Love’, written and recorded purely because the group faced the artificial deadline of a Peel appearance booked to put them under the cosh. And in the lore surrounding Heaven Up Here we encounter the same ideas: according to McCulloch, in interviews given to the UK music press around the album’s release, the group had very few songs fully written before they turned up at Rockfield Studios to begin work on the record.

Yet this claim, surely, needs to be taken with a grain or two of salt. Of these 11 tracks, two were not just already a part of the band’s live set by the end of the previous year, but would be released before the LP – ‘Over The Wall’ and ‘All My Colours’ appearing on the Shine So Hard EP, recorded live in Buxton on January 17. (‘Over The Wall’, indeed, was already a fan favourite by that stage, having been included in a Peel session recorded and first broadcast the previous May, before even Crocodiles had come out.) Three further songs – ‘Turquoise Days’, the title track, and ‘Show Of Strength’ – were recorded for the band’s third Peel session in November of 1980, and what’s striking when you compare those versions to the ones recorded four months later for the LP is how little they were changed. The most significant difference is in a title alteration: ‘Show Of Strength’ was called ‘That Golden Smile’ for the BBC recording; the same session also saw ‘All My Colours’ receive that name, where on Shine So Hard it went by ‘Zimbo’. ‘A Promise’, too, was already well in hand before the band arrived at the studio – it had existed in separate pieces, as a poem and a backing track, for some time before those were spliced during the album sessions. Still, that around half of it didn’t exist before recording began perhaps helps explain certain aspects of the record’s atmospheric cohesion.

And it’s this cohesion that is key. The harder you try to pick it apart to find out how it works, Heaven Up Here seems to push back and resist ever more strongly. Just when you think you’ve figured out that it’s the way Sergeant and McCulloch beat up their guitars to form the solos in ‘No Dark Things’ – channeling Wilko Johnson via Gang Of Four – that turns the song into more than the sum of its parts, then you find yourself realising that a lyric of even a touch less ambiguity would have thrown the whole thing out of balance and turned something truly and spine-tinglingly extraordinary into a pretty quotidian song (albeit likely still a very good one). No sooner do you feel you’ve finally cracked the mysteries of the title track by identifying Pattinson’s bass line in the pre-hook bridge as the source of the tension the verses arrive to release, than you’re suddenly aware of those little jagged, muttered, apparently wordless ad libs over to the left of the mix in the crescendo sections – and then McCulloch’s off into the wide blue yonder of the closing section, one of pop’s least constrained performances. It’s not about the parts, it’s about the whole. Nothing works unless it all does. What’s remarkable about this record, really, is that that happens all the time.

The effect this has on the listener is understandably intense, but to a degree that’s markedly notable. Plenty of musicians have written songs about books, but there aren’t that many novels written about records: John Irving’s Last Night In Twisted River is the only one that springs immediately to mind, a multigenerational family saga spun off a couple of lines in Bob Dylan’s ‘Tangled Up In Blue’. And true, Heaven Up Here hasn’t, to the best of your correspondent’s knowledge, inspired a whole book; but the album (and in particular its sleeve art) does exert a powerful force over the cast of school friends in a seaside town in 80s East Anglia in Weirdo, the mesmerising 2012 novel by Cathi Unsworth. Several of the book’s 40 chapters are titled after Bunnymen songs, but the former Sounds and Melody Maker journalist isn’t content with paying lip service. Early on, the reader follows a private detective down the corridors of a secure hospital to visit an inmate, and has a piece of her artwork pointed out to him:

"A long blue wash of sky meeting sea, four figures in black with their backs turned, gazing out at the horizon where a flock of gulls took flight. Sean was no expert, but he could see how well the subdued palette had been employed to reflect the pale yellow of the sand and the gradually darkening blue of the sea." (p19/20)

The album turns up several times, across two timelines, as Unsworth tells a story that draws deeply on a very similar sense of dread and unease that lies at the heart of not just the songs on the record but the way they are played and recorded. It’s a carefully written book, not what you would call fastidious, but precise in its choice of language and its depictions of place and time, with sharp lines used to draw its characters. And it’s no accident that it’s Heaven Up Here that takes on a central role, rather than any of the many other records evoked or mentioned – a backdrop and a linking device, a revered icon passed down the ages by initiates that acts as a clue to the reader and a signifier of something bigger, more ephemeral, more mysterious that seems to lurk beneath the surface.

This effect, it seems to these ears, is achieved because on this record – and perhaps only truly here, despite the greatness of much of what was to follow, and a great deal of what had already come – the Bunnymen succeeded in making a kind of music that can only exist within very close limits. It’s unhinged but never entirely unrestrained; untamed but compliant with certain rules or guidelines; unmoored but never lost at sea. It’s not just the outsiders and the weirdos that can get it – though it’s easy to grasp why those who feel themselves to be cut adrift from the mainstream, who feel no-one is listening and nobody gets why they should, would grab hold of music apparently made by people who intuitively understood what living like that, being inside those moments, feels like – and were able to make that understanding plain through the music they made.

Of the handful of negative critiques of the record that have been published down the years, the most striking has always been Drummond’s apparent appraisal, published originally in his short book From The Shores Of Lake Placid then republished in a longer essay in the book 45. "The album is as dull as ditchwater," he wrote. "The songs are unformed, the sound uniformly grey." This needs to be considered in its proper context, as part of a lengthy piece in which Drummond is discussing his ideas around the character of Echo, which he identifies with the trickster of Norse and other mythologies, and saw as a looming presence in Brian Griffin’s photograph on the cover of Crocodiles. It’s also possible that this reaction, even if taken at face value and considered both accurate and reliable, may have been overstated. In the next chapter of 45, Drummond muses on this himself, wondering: "Maybe it’s only shit compared to/What I wanted it to be like/In my head", before deciding that his assessment should stand. Still, it has always stuck out as a particularly surprising critique, even more so when, last year, writing on his website, Drummond spoke of seeing a Michael Jackson gig with his son in 1997 and finding that "it was not wild and uncontrollable like what I want pop music to be".

To these ears, it’s exactly those qualities – its howling wildness; its resistance to most, if not all, forms of restraint – that are most vital to making Heaven Up Here the singular and distinct record it still seems to be. So I wrote to Drummond to ask about it. He doesn’t do interviews, but did respond in the way he conducts most of his interactions with media these days, by commissioning his alter ego, Tenzing Scott Brown, to write a Forty Second Play on the subject. You can read that here. (And, if you’ve got this far, then you must, immediately. But do please drop back this way when you’re finished.)

Art is about dialogue: one that goes on constantly inside the artist, between the artist and the audience, between ourselves as we were and whoever we go on to become. In this writer’s case, those conversations are happening right this moment, as these words morph from thought to action and from keyboard to screen. They veer between what I thought and felt and experienced years ago, what I think I might know now, and are influencing and changing the versions of this piece I’ve been writing in my head before I read the Forty Second Play and the very different one that it appears I’ve ended up writing since.

Drummond correctly describes those first Bunnymen albums as a four-part artwork for the ages, and the idea that those records are involved in a series of conversations feels both apt and important. It is in that context that perhaps we can most readily grasp why those who feel such a strong attachment to Heaven Up Here – authors, fictional characters, and the rest of us alike – have come to fall under its spell. It’s a transitional record made by a band who, on one level, probably intuited that that’s all it was ever going to be; yet on another were surely only just beginning to grasp what their music might go on to become. By the time of Porcupine, of course, the conversations had moved on. Yet along the way, the Bunnymen laid down this indelible marker, achieving a permanence never to be repeated precisely because that aspect of it had never been intended. Heaven Up Here stands alone because most musicians never get to be as thorough and as committed while they’re on their way to somewhere else. If it feels like a little miracle, that may be because it manages to be both the journey and the destination: transitory and permanent – light on the waves.