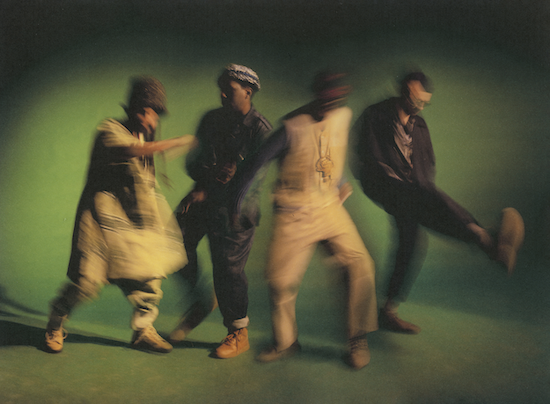

Photo by Udoma Janssen

It has become increasingly clear over the past year that Britain is a nation of bootlickers. It is a country wherein a very terrible status quo is upheld at all costs, and there is very little reason to hope for a better future.

I think back to last Summer – Black Lives Matter protests – and the backlash that followed from the UK’s press and media. “Tearing down statues of slave owners is erasing history,” someone with a Blue Tick that definitely didn’t stand in the way of mass library closures would say, before following it up with something like: “yeah, well, I think all lives matter.” A nation of bootlickers.

Over the last twelve months – no, actually, longer – way, way longer – for its entire modern history, the United Kingdom has sought to undermine Black voices and Black communities at every step. It is built on empire and on the suffering of Black people. We should all be ashamed of our country. It’s our duty to listen and acknowledge, to celebrate Black Britons and Black people globally, and to stand in solidarity against injustice at every turn.

Things cannot go on like this, and it’s time to reckon.

Visionary bandleader Shabaka Hutchings has been reckoning for a while. Hutchings is the leading light in London’s jazz scene, a prolific and skillful operator. Figurehead, hero, luminary. Whatever you want to call him, he’s it.

The last decade has seen him inverting and reshaping jazz as we know it with his groups The Ancestors and The Comet is Coming, whilst also playing with the likes of Melt Yourself Down, Kamasi Washington, Mulatu Astatke, and Sun Ra’s Arkestra. The London-born, Barbados-raised multi-instrumentalist is quickly amassing a discography to rival the greats, and if carries on at an album per year he’ll have Miles Davis and Sun Ra in his sights long before the time the Earth devolves into a fiery uninhabitable ball.

With improvisational quartet Sons of Kemet though, he’s at his very best. They are the most crucial of groups, and Hutchings is the composer and bandleader. Whilst it would be wilfully misunderstanding the point to call any of his other works apolitical because no one shouts “fuck the Tories” on them, Hutchings is a real revolutionary when fronting Sons of Kemet. The message of this music is in bold, underlined type, and it cannot be ignored. Alongside Shabaka in this group is tuba player Theon Cross, and twin drummers Edward Wakili-Hick and Tom Skinner, in turn frequently joined by a plethora of guest vocalists. The results are nothing short of astounding.

Their sound is often simply labelled ‘jazz’. Maybe because the instrumentation is 50% brass, or maybe because the joy the quartet finds improvising is only really paralleled in the jazz world. But this is something different. A taste of jazz perhaps, but with heady hints of dub and hip-hop, of Caribbean Soca and afrobeat, and of techno and 2-step in perfect harmony. Everything that has come before inspires Sons of Kemet, but this is no rehash. The way in which the group deliver it: such force, gusto, whirlwind and bombast; such urgency and such tenacity; two jacked-up drummers and the swampy buzz of a tuba. Maybe this is jazz, Jim, but not as we know it.

2018’s almighty Your Queen is a Reptile, their third album and first for Impulse!, was their real breakout. The message that runs through that record is as plain as day – look at the tracklist, and then the album name.

“It’s about the myths that we take as a given,” Hutchings told the Soundcheck podcast’s John Schafer: “I challenge you to define your queen.” ‘My Queen is Angela Davis’, ‘My Queen is Harriet Tubman’… Your Queen is a Reptile.

The record features a few powerful guest vocalists, chiefly an abrasive monologue from poet Joshua Idehen. But the song titles anchor the quartet’s wild-eyed noise to a wider concept. ‘My Queen is Harriet Tubman’ is an incendiary interpretation of Tubman’s turbulent initial escape from slavery, whilst ‘My Queen is Ada Eastman’ repurposes the fiery attitude of Hutchings’ Barbadian great-grandmother, the family matriarch who lived well into her hundreds.

New album Black to the Future arrives next Friday, and its tracklist also reveals a manifesto of sorts: the best place to start when unpacking its brilliance. “The track titles all combine,” says Hutchings, “to reflect a single poetic statement to which a depth of symbolic meaning can be intuited in combination with the music/sonic information.” It reads: “Field negus – pick up your burning cross – think of home – hustle – for the culture–- to never forget the source – In remembrance of those fallen – Let the circle be unbroken – Envision yourself levitating – Throughout the madness, stay strong – Black.”

It would be reductive to boil Black to the Future down to this, but it provides an excellent entry point. It is not simply a glib diagnosis or a gloomy cultural prognosis, but offers eventual hope of a cure. Hutchings calls the album “a sonic poem for the invocation of power, remembrance and healing,” envisioning a future where, “indigenous knowledge and wisdom is centred in the realisation of a harmonious balance between the human, natural and spiritual world.”

Whilst much of the band’s prior material was shaped live, finding its final form in sweaty venues, that has simply not been the case with Black to the Future for fairly obvious reasons. Whilst there are moments of fizz, pure energetic zip, the album as a whole is more meditative. For the most part, Hutchings favours clarinet over saxophone, welcoming brass contributions from the likes of Steve Williamson, Kebbi Williams, and Cassie Kinoshi of SEED Ensemble. In this slight transformation, though, nothing has been lost.

Tracks like ‘Never Forget the Source’ and ‘Envision Yourself Levitating’ reach slow sprawling ecstasy through patient constructions. The latter especially, sees Hutchings’ woodwinds and Kebbi Williams’ tenor sax dovetailing around Cross’ wilting brass bassline daintily in pursuit of the absolute. It’s transcendent stuff.

Rap music – both West Coast and grime – shapes Black to the Future. Hutchings makes no secret that the flows of Biggie, ‘Pac and E-40 (“hip-hop’s Eric Dolphy”) have been an ever-present influence on his melodies, and he’s keen to talk about the relationship that London’s jazz scene shares with its grime scene. “I’ve always seen grime as just another manifestation of what I’m doing,” he tells Dave Cantor for the album’s liner notes: “taking the music of the Caribbean, and altering it for the context of being in London”.

It’s no surprise then, that Black to the Future welcomes a couple of MC collaborations, and that they work perfectly. Cross’s tuba is taut and tense as it prowls around Kojey Radical’s guttural verses on ‘Hustle’, whilst Lianne La Havas counters breezy backing vocal harmonies. Meanwhile, on ‘For the Culture’, the wildly inventive vocalisations of grime MC D Double E are met with some of Hutchings’ best melodies, spiralling woodwinds and meandering bars in a double helix. Hutchings’ melodies interplay so well with the MC, a proper call and response chemistry going on.

Perhaps, though, Sons of Kemet remain at their best when they ramp the intensity right up. ‘Pick Up Your Burning Cross’ features a busy two-drummer scuffle, whilst Cross gets a real Harley Davidson rev out of his tuba. It’s pure sonic arson – the hellfire of Moor Mother’s spoken word sets the track aflame, whilst Hutchings’ clarinet is incandescent in the background.

Josh Idehen, whose volatile spoken word opens their 2018 effort, bookends the album, with eloquent and barbed poetic verse on ‘Field Negus’ to open the album, and ‘Black’ to close it. These are perhaps the album’s highest and most affecting passages. “You had me saying prayers in your language,” Idehen thunders on the opener: “You made me forget your gods, question my spirits, forsake my prophets.” His voice quivers with rage as he decrees with vengeance: “We’re rolling your monuments down the street like tobacco, tossing your effigies into the river… burn it all, burn it all.”

Idehen’s fury is matched twofold in Sons of Kemet’s skronk. Shabaka is joined by UK jazz veteran Steve Williamson, their twin tenor saxophones squall sordidly in tandem as they swoop into writhing Ornette Coleman Naked Lunch territory. Similarly, the closing salvo ‘Black’ marries an escalating Idehen monologue with what sounds like an off-piste free jazz funeral march. “Just leave black be,” he screams over unheimlich brass grot: “Just leave us alone!”

The ground covered on Black to the Future is immense. The visceral passages really slash deep, the moments of unbridled energy are exhilarating, and the meditative moments reach crescendos of total beauty. The world is terrible for a whole manner of reasons, in dire need of reshaping. It would certainly be naive to pretend one record could change that, but when this quartet are in full flow it is at least possible to hope.